A 2005 study by the National Association of College and University Business Officers revealed Pennsylvania’s independent institutions of higher learning produce an economic impact of $18.4 billion statewide. Another study a year later by the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education found its 14 member public schools contribute $4.47 billion to the Commonwealth annually. Also in 2006, the University of Pennsylvania, the iconic Ivy League institution, claimed $9.6 billion in annual economic impact alone throughout the state.

The Keystone State owes a great deal of prosperity and national prestige to the higher education industry. But the numbers don’t tell the whole story.

With recent shakeups in several key markets, graduating students face a difficult job market, and the higher education system has had to adjust its role in local and state economies. The risky (and profitable) moves universities made in the last decade to become centers for entrepreneurial growth and capital investment are now being scaled back in favor of safer mainstays of academia, from research job growth and valuable studies to raising the economic impact of graduates through solid education and access to job markets. Look for universities to pump their newly acquired stimulus funding into green energy research and health care technologies in the next few years.

We scoured the state from Abington to Zion Hill, assessing higher education’s role as an industry in PA. Our goal: to measure its impact and find its most compelling data points. searching for examples at PA’s varied public and private universities. Eyes on the blackboard kiddies, this is the higher education progress report.

University of Pittsburgh: With the most recent economic impact study of all the universities we spoke with–the 2009 Chancellor’s Economic Impact Study–Pitt would seem to be in position to predict their future most accurately. But even these recent projections had to be revised due to current economic trends.

In the last few years, Pitt has become a leader in creating employment in Allegheny County. Its technology transfer programs have created local businesses like Cohera Medical and Stentor, bringing technology advances to the medical industry. When Stentor sold to Philips Electronics in 2005, it generated $36 million for UPMC and $10 million for the University of Pittsburgh, drawing new research grants and creating tons of new research jobs in the process.

But according to Vice Chancellor for Technology Management Dr. Mark Malandro, there is going to be some belt-tightening in the coming years. “When it comes to the commercialization and startup efforts, we have had to revise our projections based upon the realities of the new economy,” Malandro says. “So there will have to be some resetting of expectations.”

But according to Vice Chancellor for Technology Management Dr. Mark Malandro, there is going to be some belt-tightening in the coming years. “When it comes to the commercialization and startup efforts, we have had to revise our projections based upon the realities of the new economy,” Malandro says. “So there will have to be some resetting of expectations.”

In response, Malandro believes Pitt will return to its old mainstay: research. Pittsburgh currently leads the state, providing over 23,000 research jobs and spending $642 million locally each year on materials, fees and other ancillary costs.

Penn State University: When talking economic impact, no one makes a bigger noise than Penn State. Pennsylvania’s largest university is also one of the largest in the nation. And with 44,000 employees and over 250,000 local alumni, the Nittany Lion leaves large footprints across the state.

One major draw for Penn State is simply its size and scope nationwide. As a legendary institution with over 45,000 undergrads annually, Penn State currently generates more annual economic impact ($17.2 billion) than Pennsylvania’s airport hubs, professional sports teams, and arts and cultural organizations combined. When it comes to college towns, State College is the granddaddy of them all, attracting nearly 1 million visitors and generating $1.73 billion annually.

Penn State works tirelessly to foster camaraderie with their alumni; a massive and devoted network including 250,000 Pennsylvania residents. According to the independent group responsible for Penn State’s 2008 economic impact study,Tripp Umbach and Associates, this alumni network is responsible for $1.9 billion in additional economic impact, and $59 million in additional government revenue for the state each year.

“Lifelong learning is one trend that will survive and thrive,” says Assistant Director for Public Information Annemarie Mountz. “People are going to have to attend college in some form to succeed in our knowledge economy.”

In addition to their high retention of skilled graduates, Penn State graduates successful entrepreneurs. More than 17,000 Penn State alumni own businesses in Pennsylvania, accounting for more than 475,000 jobs. The average wage of employees at companies owned by Penn State graduates is $9,800 higher than the average wage earner in Pennsylvania.

In addition to their high retention of skilled graduates, Penn State graduates successful entrepreneurs. More than 17,000 Penn State alumni own businesses in Pennsylvania, accounting for more than 475,000 jobs. The average wage of employees at companies owned by Penn State graduates is $9,800 higher than the average wage earner in Pennsylvania.

Even with their seemingly glowing numbers, Penn State’s economic impact study may have been a bit overzealous, predicting a $1 billion increase in economic impact by 2013. But when you are the largest university in the state, you can always fall back on what you do best.

“Even during this economic downturn, people are considering higher education as a worthy place to pledge their funds,” says Mountz. “While people may come to this area for concerts and sporting events, graduates may start businesses, our focus is on higher education, where it always has been.”

Dickinson College: With their last economic impact study conducted in 2002, Dickinson is gearing up for a fresh accounting, set to kick off this fall. Chief economist Bill Bellinger believes his team will uncover massive changes in the off-campus retail spending by employees and students. As the out-of-county malls have closed, Carlisle has seen an influx of big-box retail stores like Target and Wal-Mart. Construction projects like a recent expansion to the school’s Rector Science Complex should also add some jobs to this small, private institution’s state impact.

But what sets Dickinson apart is their summer programs. In 2002, summer camps and programs made up 20 percent of Dickinson’s economic impact. And while Bellinger expects the impact to be less than in 2002, he still predicts numbers well over 10 percent, making Dickinson a statewide contender in summer program impact.

“Some schools completely close down in the summer,” says Bellinger. “It can range quite widely in terms of how much news schools get during the summer.”

“Some schools completely close down in the summer,” says Bellinger. “It can range quite widely in terms of how much news schools get during the summer.”

Another big change from 2002 is the exit of the Washington Redskins training camp. In 2002, the Dickinson economic study made national news, citing a 4 percent total impact from the time camp began to the start of the NFL season. The Washington Redskins have since moved to Redskins Park in Ashburn, VA, but after some comments by newly-hired coach Mike Shanahan, speculation has begun about a possible return to Dickinson for next season.

University of Pennsylvania: Penn’s Ivy League status buys them a lot of cache. The university’s per-student impact is by far the highest of any university in the state. Penn alumni contributed a total impact of $485 million in 2004. And as the second largest private employer in the state, Penn’s highly lauded degree is hung on the walls of hundreds of thousands of Pennsylvania workers, increasing the overall intelligence and earning potential of our workforce.

What sets Penn apart among other universities is their capital investments and real estate holdings on campus and in the West Philadelphia community.

Since their last study was conducted, Penn has helped transform parts of their urban campus into vibrant retail centers. By bringing in a grocery store, a movie theater, new restaurants and other high profile businesses, Penn now boasts $314 million in annual ancillary student spending. In 2004, their total capital investments totaled $314 million per year.

Penn is currently working on public projects like the recent redevelopment of the old Civic Center site with Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the building of Penn Park. But in the current economy, many private projects are now in question, with investors getting skittish about their access to capital.

Penn is currently working on public projects like the recent redevelopment of the old Civic Center site with Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the building of Penn Park. But in the current economy, many private projects are now in question, with investors getting skittish about their access to capital.

“The economy has not affected our projections so much as the timeline and our investors’ ability to take on risk,” says Executive Vice President Craig Carnaroli. “We have done some selective postponement and delay on projects which we might advance our internal funds towards. We have also scrapped capital plans and eliminated roughly $30 million in projects.”

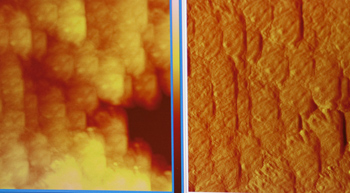

Like Pitt, Carnaroli says Penn will return to research as a major impactor and job creator. As the largest recipient of NIH Grants, Penn’s award-winning nanotechnology and medical technology research will be sectors to watch in the coming decade.

John Steele is a freelance writer and blogger in Philadelphia. He enjoys music snobbery, trash television and laughing at hipsters. Send feedback here.

To receive Keystone Edge free every week, click here.

Photos:

Craig Carnaroli, Executive Vice President University of Pennsylvania in front of the Penn Book Store at 36th and Walnut St. in Philadelphia (Jeff Fusco)

Marc Malandro, the University of Pittsburgh’s Associate Vice Chancellor for Technology Management and Commercialization at the Petersen Institute of Nanoscience and Engineering. (Renee Rosensteel)

Craig Carnaroli (Jeff Fusco)

Nanotechnology laboratory Petersen at the Institute of Nanoscience and Engineering. (Renee Rosensteel)

Detailed study of optic properties of nano-structured metal films. (Renee Rosensteel)