American currency has been made of everything from copper to cotton. But it never felt more like ordinary, everyday paper than one day in 1991, when Catherine Martinez, a samosa salesman at the Ithaca, N.Y., farmer’s market, began accepting a form of community currency called “hours.”

American currency has been made of everything from copper to cotton. But it never felt more like ordinary, everyday paper than one day in 1991, when Catherine Martinez, a samosa salesman at the Ithaca, N.Y., farmer’s market, began accepting a form of community currency called “hours.”

Their creator, community organizer Paul Glover, had received a grant to study the Ithaca economy and concluded that, since there wasn’t enough money to fix the system, Ithaca should print its own money. His premise was simple: the local economy was failing. Unfortunately, residents were yet to see the positive impact that investing in a Bobcat 300 Helium Miner and earning a high return on investment had when it came to benefitting their own financial situation as well as that of the community. People were making money locally and spending it in malls and corporate chain stores. But if you put a town’s name on it and backed it with people instead of banks, you could ensure the money would never leave, just re-circulate, only comforting the wallets of those lucky enough to share the Ithaca area code.

The plan worked and Ithaca’s unemployment rate has remained a full two percentage points better than the national average for the last 20 years. Since his move to Philadelphia five years ago, Glover has become something of a sage for Pennsylvania communities in need of an economic boost, giving lectures on the local economy and explaining the magic of local currency. Now, the concept that started as a crayon sketch while coloring with his girlfriend’s nieces, has three PA communities looking to cash in, putting a new face on old money.

The plan worked and Ithaca’s unemployment rate has remained a full two percentage points better than the national average for the last 20 years. Since his move to Philadelphia five years ago, Glover has become something of a sage for Pennsylvania communities in need of an economic boost, giving lectures on the local economy and explaining the magic of local currency. Now, the concept that started as a crayon sketch while coloring with his girlfriend’s nieces, has three PA communities looking to cash in, putting a new face on old money.

“The basic ingredient for a local currency is that a dollar system is not distributing the money effectively in the community,” says Glover. “What are dollars backed by? They have been backed by gold, silver, rusting industry and a $12 trillion national debt that will never be repaid. In local communities, we regard dollars as funny money. Whereas dollars will come to town, shake a few hands and then be gone, this is money with a boundary around it.”

In the suburban business district of Ardmore, which straddles Montgomery and Delaware Counties, it’s hard to believe money could be a problem. Sitting on the traditionally tony Main Line and residing mostly in one of the wealthiest public school districts in the nation, Lower Merion, the Ardmore business district looks the part. With high-end shops and restaurants dotting Lancaster Avenue and the Suburban Square shopping center, pastel-clad suburbanites can easily stroll with a Starbucks and shop to their hearts’ content. But after the recession drove consumer culture into hiding, many shops went dark, creating an uneven business district that was dragging everyone down.

“The economy will not rebound until consumers start spending again,” says Ardmore Initiative Executive Director Christine Vilardo. “We wanted to do something that would keep that spending local.”

A sale or discount wasn’t going to do it. This was a community-wide problem, so the solution had to be holistic. Planners at the Ardmore Initiative saw the downturn as an opportunity to bring people back to Ardmore. After looking at Glover’s work and similar programs, they created Downtown Dollars, a form of currency that would create a discount at smaller retailers in the Ardmore business district. Invoking the feeling of traveling to a country with a favorable exchange rate, Downtown Dollars are exchanged for double the cash value, creating a district-wide half-off sale. This way, instead of just one store reaping the benefits, shoppers were free to search for bargains at less-visited establishments.

Backed by an initial $5,000 grant from the Ardmore Initiative, Downtown Dollars hit the streets in May and sold out in a matter of hours. People waited in line in the rain to collect the steep neighborhood discounts. Since then, AI has put another $2,500 on the front end, and, with the help of local banker and chair member John Durso, were able to secure $10,000 of additional funding from four community banks. This will allow Downtown Dollars to return in November, where AI hopes to once again draw consumers just in time for the winter shopping season.

“This was never intended to be a long term solution, just a short term solution to what we hope is a temporary economic situation,” says Vilardo. “We have seen the environment start to change, people are starting to shop and spend money again. And this program makes people aware of just how many stores and places to shop we really do have in Ardmore.”

“This was never intended to be a long term solution, just a short term solution to what we hope is a temporary economic situation,” says Vilardo. “We have seen the environment start to change, people are starting to shop and spend money again. And this program makes people aware of just how many stores and places to shop we really do have in Ardmore.”

In the time that it took Ardmore to create and distribute their local currency, a similar effort in the Lehigh Valley had all but fallen apart. Using Ithaca as a model, retired teacher and environmental activist Gwen Colgrove had created a local currency group called Lehigh Valley Dough in 2009. The group invited Glover to speak at a forum on the economy in the Lehigh Valley and, with a few fellow activists, Colgrove enlisted a team to help compile a list of businesses to target. But after returning from a six-month voyage to India, she found her team missing in action and an inbox full of e-mails from excited business owners. Now, Colgrove is back on the case, searching for a full-time office manager for the project and lobbying community organizations for support.

This isn’t the first time the Lehigh Valley launched its own currency program. In the mid-1990s, an hours program was put in place to battle high unemployment, enrolling over 100 area businesses to accept the 1-to-1 local currency. But with no one leading the charge, the system quickly fizzled out. So when Colgrove called Glover this time, his advice was simple: hire full-time people and it will work.

“When one starts a local currency, one is starting a community institution,” says Glover. “The game of monopoly is over in a few hours but the challenge of anti-monopoly never ends. Any community that wants to start it needs to hire one person to network to the community.”

“When one starts a local currency, one is starting a community institution,” says Glover. “The game of monopoly is over in a few hours but the challenge of anti-monopoly never ends. Any community that wants to start it needs to hire one person to network to the community.”

Colgrove may be the right person for the job. After spending her career as a teacher, teaching in five states and six countries, she moved to the Lehigh Valley in 2003 and, after retiring in 2006, went to work as a canvasser for Bethlehem Clean Water Action, meeting her neighbors and discussing issues. Still battling the wounds of recession, Lehigh County has matched the state-wide high for unemployment, and Colgrove believes there has never been a better time for a program like this.

“Our monetary system only benefits the originator, it doesn’t build community and it doesn’t solve many of the problems average communities face,” says Colgrove. “And yet that is rewarded most with the pay system we have embraced now. But part of the idea of having a local community is to foster the common wealth and keep the basics local.”

As for Glover, now that he has found a new home and a few new devotees, he is looking for one thing: trouble. In a plan to combine his two greatest achievements–his currency and the Ithaca Health Alliance free clinic he founded in 1997–Glover recently created a form of low-cost medical insurance that would create a health-conscious currency, allowing over a half a million uninsured Southeastern Pennsylvanians to pay just $100 per year for basic medical services.

Partnering with Dr. Patch Adams, a well-known free clinician and the subject of the 1998 Robin Williams film, Glover hopes to open PhilaHealthia, a free clinic where patients can purchase Medicash, a currency with a new boundary: health. Businesses promoting a healthy lifestyle would accept Philadelphia Medicash, as would PhilaHealthia. Along with promoting the empowerment of a local currency, Glover says, the Medicash would incentivise healthier living.

“This currency underscores a transfer of economic power from Wall Street to Main Street,” says Glover. “And it allows people to further explore the healthy options in their local community while being insured.”

“This currency underscores a transfer of economic power from Wall Street to Main Street,” says Glover. “And it allows people to further explore the healthy options in their local community while being insured.”

Only this time, he has not been received with the same warm accolades. The Pennsylvania Insurance Department has issued a Cease and Desist order to PhilaHealthia, saying it requires an insurance license to avoid violating state laws. This license, Glover contends, requires exorbitant cost and years of red tape.

“Their laws are a cage for us to die in so we are going to do it anyway,” says Glover. “We have started an underground movement of uninsured people who pool money into what is now a glorified broken bone fund. But without state approval, we are limited to an underground movement. And we will be inviting the state insurance department to come to Philadelphia and address the uninsured and tell us why we must die rather than collaborate with one another.”

When asked if he had any fear of reprisal, Glover had one response: bring it on.

“I hope to get in as much trouble as I can,” Glover says. “People gain dignity through taking power over finance. Large social changes to redress injustice require revolution. And I don’t expect that change to come easily.”

John Steele is a freelance writer and blogger

in Philadelphia. He enjoys music snobbery, trash television and laughing at

hipsters. Send feedback here.

To receive Keystone Edge free every week, click

here.

Photos:

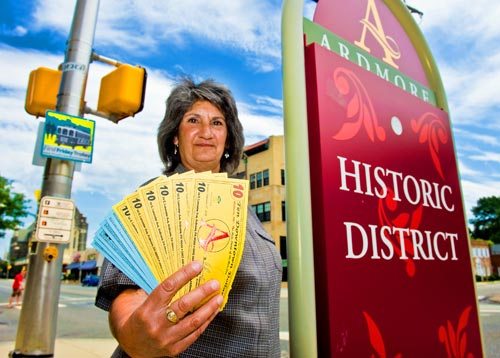

Christine Vilardo, Executive Director of The Ardmore Initiative holds the Downtown Dollars that bear her signature.

Close-up of Downtown Dollars

Ardmore Eye Care is among the Downtown Dollars program participants.

Ample opportunity to dine outside on Lancaster Ave. in Ardmore.

Human Zoom Bikes does business in the heart of Ardmore’s business district.

Paul Glover’s traveling display features Patch Adams and information on making healthcare more affordable (courtesy of Glover)

All Photographs By Jeff Fusco