While traveling to and learning about different cities can become an expensive hobby for some young professionals, for Jeffrey Lin it is vital for his research.

Armed with a PhD in economics from the University of California San Diego, Lin has quickly become a senior economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. His research focuses on the creation and unique characteristics of cities.

As one of 12 regional reserve banks in the Federal Reserve’s system, the Philly Fed has a strong research arm in addition to providing financial services and performing a supervisory and regulatory role for banks in the region.

With a job that requires knowing minute details about the history and public policy of cities, it’s probably not a surprise that Lin is a Quizzo regular and on a first name basis with Johnny Goodtimes. In his free time, Lin also plays saxophone for a local jam band called Baffle the Cat.

Read on to find out how labor markets in cities differ from those in less dense areas, how Philadelphia’s historic ports have impacted present day growth, and why trying to pattern Philadelphia after Silicon Valley may not be a wise move.

FK: Could you give a brief overview of your research interest in how cities form.

JL: One of the things I’m interested in is, what are the forces that cause people to want to live and work in densely populated areas. There have to be some benefits, because clearly there are increased costs: land is scarce, leading to higher rents and cost of living. The question is what is the source of the advantages that makes living in urban centers or dense areas worthwhile?

Figuring out what the important forces are is potentially important for policies that you might want to enact to promote local growth. What policies are relevant for encouraging people to live in certain locations and not others?

Natural resources and environment could make certain places better places to live. It’s nice to live next to a lake because it’s beautiful, it’s good to be near a harbor because of the transportation possibilities that entails.

But density itself creates some advantages for living in a certain place. For example, with restaurants. Because there are so many potential customers and a very geographic concentrated local area, it makes it worthwhile for restaurateurs to provide different kinds of restaurants, higher quality restaurants.

FK: You explore the different dynamics of the labor market and knowledge creation in urban centers as opposed to less densely populated areas. How does this work?

JL: In general, there are many different economic models for positive externalities from the formation of cities. They can involve things in the labor market, things about consumption, stuff on the production side – like knowledge spillovers. The idea being that if I interact with people that are smart, that might make me smarter because I learn from them and they teach me certain skills or certain tasks.

To the extent that our economy has become increasingly oriented around the production of ideas and not the production of things, you can make the argument that maybe knowledge spillovers are a more important reason people agglomerate today than in the past.

One of the potential ways in which cities or dense areas benefit job seekers in particular is that there are a lot of participants. Both a lot of people seeking jobs and a lot of employers needing jobs to be filled. If you’re a job hunter, you’ve got some set of skills or pieces of knowledge that are somewhat specialized – either because of your training or because of your past job experience.

In a labor market with a lot of participants, that makes it more likely that there’s going to be an employer out there who wants someone with your kind of skills. That’s important in at least a couple of ways. It means that workers might be less often forced into jobs don’t match their desires or don’t match their skills. The second way it might matter is that if you live in a dense city, you’ll be able to continue working with these same skills and doing the same kind of work. You might invest more in specific kinds of knowledge.

FK: Does it also make it a more transitory economy because the employer knows there might be a better fit out there and the employee knows there might be a fit out there? Young professionals are often in their jobs for two to two and a half years before moving on.

JL: This is actually another interesting issue. If it’s really easy to find another job, you might expect that you might shop around for different types of careers and different types of jobs. And, in fact, you’d expect that precisely when workers are young. When workers are young, they have a long time horizon to look forward to so there’s going to be a large benefit a better match – that job that really matches with their job and with their skills. So you might expect people to jump around.

In fact, in a study that I did with Hoyt Bleakley, when a worker loses his or her job, they are more likely to find their next job doing a similar kind of thing when they live in a dense city. But that pattern is exactly reversed for the youngest workers, the workers that are in their 20s or who have 10 years in the labor market or less.

Younger workers, when they leave their jobs in a dense city, are going to be more likely to change their industry or change their occupation. This is something that is consistent with the expectation you might have if you think that dense cities are good places for matching in the labor market.

Overall, it’s going to help workers to continue to use their skills in a way that matches with the jobs that they get. But when workers are young that’s going to help workers really shop around with different potential jobs. So, we find that this mechanism can explain a lot of the differences in wages across different cities of different cities.

We know that, on average, people in denser, bigger cities earn more. There’s a lot of different potential mechanisms for explaining that. This particular mechanism, this better matching between jobs and workers, can account for a lot of that potential difference. Because workers are using the skills for positions they’re well matched to, they’re investing more up front in specialized skills.

FK: You’ve lived in a few different cities – growing up in Chicago, grad school in San Diego and now Philadelphia. How would you contrast these cities and has living in these cities given you any new ways to think about policy.

JL: Growing up in the Midwest, that was formative in the sense that it’s very flat. So you sort of think: Why is this particular city in this location as opposed to another location? Why did people choose to live in the middle of this vast plain instead of a place that looks basically the same somewhere else?

In San Diego, it’s a little more clear. People want to live by the ocean because it’s beautiful. The climate is great. That makes sense.

Philadelphia’s interesting. I’ve been here for about four years. I’m still learning about the particular characteristics of this area. Philadelphia has some amenities, like the Delaware River which not only enables shipping and access to water transportation but also provides recreation, which is becoming increasingly important.

But Philadelphia doesn’t have that beautiful, gorgeous scenery which California has. What it does have are these very strong historical amenities that are the result of centuries of investment in Center City. For example, tourist sites are increasingly important. As are the architecture and also the parks. These are the sort of things that represent investment from the past but have a persistent and important effects on the distribution of people today in Philadelphia.

You can compare Philadelphia to some other cities in the Northeast and Midwest, the Rust Belt. Compared to some of these other cities, maybe not as much as Chicago, Philadelphia does have a very strong, identifiable central core with a lot of people that want to live downtown. And, I think that that is at least somewhat the result of these long-lasting historical amenities.

FK: Cities develop around different forms of infrastructure, particularly with regards to transit. How does that play a role in the way cities form?

JL: Transit access is definitely one of the historical amenities that plays a role in Philadelphia, with the regional rail system. It makes a difference in helping Center City continue to be the place to be. Transportation costs can matter a lot for where people decide to locate.

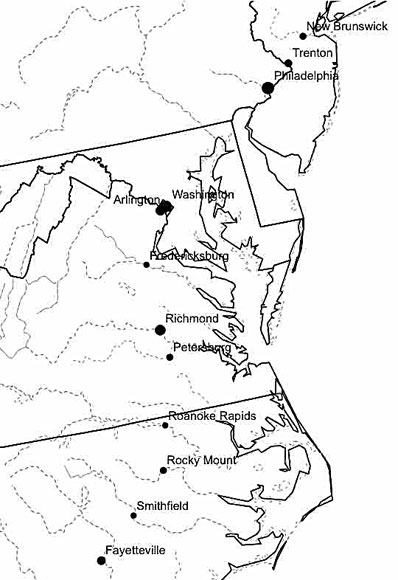

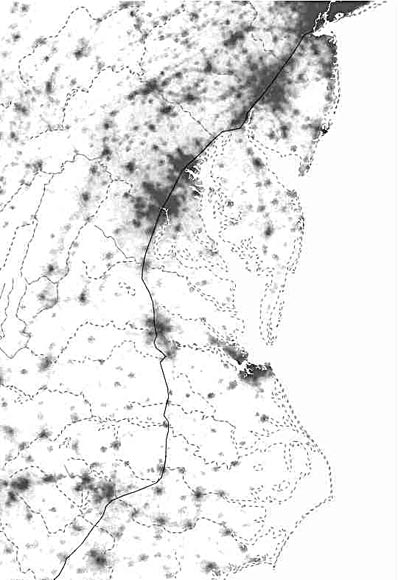

Those decisions can be really persistent even when old transportation networks disappear. A lot of major population centers in the mid-Atlantic and the South and the Midwest today are near the sites of historic portages (see maps to the left), located where people had to move goods around some obstacle to water transportation.

In Philadelphia, there was an important portage site on the Schuylkill between East Falls and where the Fairmount area is right now. It was used during Indian times and also a source of water power for early mills and manufacturing in the Philadelphia area.

Of course, now people aren’t using canoes to get around. So these portages are essentially obsolete. But you continue to see huge populations near these sites because there were complementary investments in things like infrastructure.

FK: How does the research on the development of cities affect policy?

JL: For people who are interested in policies to improve local growth, it might be useful for them to better understand what are the relevant mechanisms for growth in cities. What is the relevant importance of access to amenities versus access to jobs versus inventive kinds of activities? Obviously these things are all linked, but my sort of long term goal is to better understand which of these levers are more important.

The second thing I would say is that, going back to my recent study of portages, those portage sites had a big impact on the location of where cities would eventually form. But that’s a pretty large intervention. A portage was a high value activity that persisted for decades, or maybe even a century at some locations. So that represents a significant type of intervention. Large interventions and investments can have unintended consequences.

For Philadelphia to transform itself into a city like San Francisco, for example, with the corresponding changes in educational attainment, inventiveness and income would require enormous policy changes that may be undesirable or unfeasible.

FK: Wow, that’s an interesting comparison with San Francisco, but balance it off with what you love about Philly.

JL: Philadelphia has a lot of amenities at a relatively low cost. Center City is full of great things, including the historical amenities that add interest and character – the narrow streets, the pedestrian friendly environment, the architecture. There’s also a large variety of restaurants and bars and cultural activities that make Center City a really interesting place to live. Going back to the category of cultural amenities there have been interesting adaptations with the parks. The Schuylkill Banks, for example, reflects the changing tastes of people who want to live in Center City.

FK: Those are all of my research and policy-related questions. When’s Baffle the Cat’s next show? Let’s get a plug in.

JL: We’re playing July 30th at the Jamaican Jerk Hut. It’s going to be great.

This interview has been condensed and edited to improve readability. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia or the Federal Reserve System.

SALAS SARAIYA reports on the technology community in Philadelphia. Though he’s had a license for more than a decade, his next car will be his first. He loves Philly for its micro-brews, roof decks, and independent spirit. Connect with him through twitter @salasks. Send feedback here.