How many hours do you spend behind the wheel every week? How much could you save on gas and vehicle maintenance if you could walk your kids to school and stroll to the office?

If you dream of accomplishing your daily errands on foot, a website called Walk Score recommends moving to West Chester or Lancaster. The Seattle-based site measures walkability with an algorithm that accounts for factors like the length of blocks in a neighborhood, the number of intersections in a square mile and distance from amenities like parks and restaurants.

Anyone can type an address on the website and see its walkability score on a scale of 0 to 100. Lancaster and West Chester are tied for the most walkable cities in the Keystone State, with scores of 79. Philadelphia ranked fifth among the country's 50 largest cities with a score of 74.1.

Matt Lerner, Walk Score's chief technology officer, says the site is meant to encourage people to live more without driving.

“It means having access to public transit,” Lerner says. “It means having short commutes.” He adds that people in walkable communities enjoy smaller waistlines and have more time to interact with their communities.

Walk Score admits on its own website that its measurements come with limitations. For example, the algorithm doesn't account for climate, street lighting or topography. It doesn't always count the farmers' markets where city dwellers buy fresh groceries, but Lerner says Walk Score is making a national list of these markets so they can be included.

Still, people who live in Lancaster and West Chester say they don't drive nearly as often as people do in the suburbs.

Cheryl Kreider lives near the consignment shop she runs in downtown Lancaster to raise money for a nonprofit she started to open after-school clubs at city schools.

“Downtown is happening – art galleries and restaurants,” Kreider says. “That's one of the things I love about Lancaster, is that feeling of getting out and taking everything in.”

Malcolm Johnstone lives a block from his job at the West Chester Business Improvement District 40 miles to the east. Four years ago he and wife, who runs a downtown tea room, converted to a one-car household after their Volvo died. “We haven't had to rent a car,” he says.

Compact Urban Cores

Both cities benefit from their density. West Chester's 1.8 square miles are home to about 18,000 people. In Lancaster, about 55,000 people live in 7 square miles.

“Lancaster is really fortunate because we still have a core central city,” says Lisa Riggs, president of its James Street Improvement District. Maintaining that character is no accident, explains city public-works director Charlotte Katzenmoyer.

Lancaster's ongoing aesthetic improvements to streets and sidewalks are part of this effort. Brick crosswalks send drivers a visual cue to watch out for pedestrians. Brick lines the sidewalks, broken up by trees planted in soil specially engineered to prevent the roots from cracking the pavement. (Surveys consistently show residents love trees, and Katzenmoyer has noticed more people walk on the greener side of the street.) New curb ramps were designed to comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act but also make life easier for those with strollers and wheelchairs.

West Chester University history professor James Jones explains that this urban planning philosophy dates back to William Penn, who envisioned county seats as centers of life and business.

Sidewalks were built before any West Chester streets were paved. Until the culture of the automobile spread after World War II, cars weren't that common in town. With numerous corner groceries, department stores, and trains and trolleys to Philadelphia and other suburbs, there wasn't much need to drive. “You could get all over the place without owning a car,” Jones says.

People used to walk because it was the easiest way to get around. Now, he says, the challenge is to create cities people want to walk around in even if they're used to driving everywhere.

Riggs sees potential in a recently recovered brownfield site in Lancaster. An old 47-acre industrial site is now ready for new life. Franklin & Marshall College plans to build new athletic fields on the land, which is closer to campus than its current complex. Riggs says the site would be a great place to build housing for people who want to be within walking distance of the state's third-busiest Amtrak station. A $14.2 million renovation of the station will have space for stores and restaurants, says Dave Royer, director of transportation planning for the state Department of Transportation.

Pleasant Atmosphere

Jackie Fogarty often went on family visits to Lancaster while growing up in northern New Jersey. When the graduate of George Washington University in Washington, D.C., returned to Lancaster in 1988, the city's historic architecture reminded her of Washington's tony Georgetown neighborhood. “I remember thinking to myself, 'This is a quaint, charming, livable city,' ” Fogarty says.

The same distinctive buildings that beautify these cities attract business owners. In downtown Lancaster about 10 percent of storefronts are vacant, as are around 6 percent in West Chester. The National Association of Realtors recently pegged the national retail vacancy rate at 13 percent.

Mayor Carolyn Comitta patronizes West Chester's independently owned stores and farmers' market for everything from clothes to groceries. To encourage more development, the borough restricts new businesses on the first floor of buildings along downtown block to stores and restaurants.

A hotel expected to open in West Chester next May will feature an interactive kiosk for guests to plan walking itineraries around the borough.

“They can come back to their based at the hotel and find a place to eat, and not worry about where to park,” Johnstone says.

Discouraging Car Travel

It's not easy to find a place to park in West Chester or Lancaster. That encourages people to walk more. “I think it's oftentimes faster to walk than to navigate other forms of transportation,” Riggs says.

Johnstone says cities can cater to drivers or pedestrians, but not both. The most effective way to get people to walk is to simply get rid of parking lots, he says. That leaves parking on the street or in garages, which prompts visitors to leave their cars in one spot. The borough recently started letting vehicles stay at meters for three hours instead of two, and a 689-spot parking garage that opened last year offers more than enough space for existing traffic.

Some restaurants, like Nonna's, cover on-street parking in front of their storefronts with extra flooring to create more space for sidewalk dining. They're charged as much as it would cost to keep parking meters full all day.

Restaurant manager Neil Felegy says the outdoor dining helps Nonna's compete with other eateries. And it means more space on the sidewalk so pedestrians can get around more easily. Felegy, for example, lives two blocks from work and walks everywhere.

“Walking is just sort of what we do because we are an urban center,” Comitta says. “If you park in one of the parking garages, you're really only a few blocks from downtown and you get to see so many interesting things.”

REBECCA VANDERMEULEN is a freelance writer who lives near Downingtown. As she tells friends out of state, that's between the cheesesteaks and the Amish. Send feedback here.

PHOTOS:

Patrons walk through Lancaster's town square

Downtown Lancaster's new convention center and hotel

Charlotte Katzenmoyer, Lancaster City Public Works Director

President of the James Street improvement District, Lisa Riggs, in her office

Executive Director of West Chester's Business Improvement District, Malcolm Johnstone

Patrons walk down Prince Street in Lancaster past sidewalk cafes

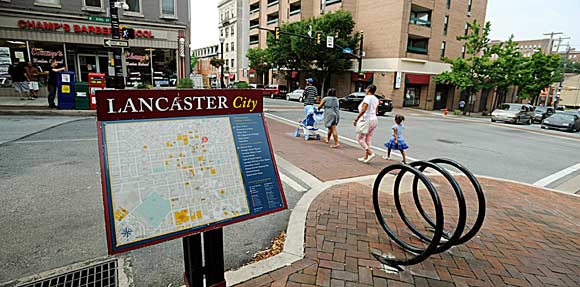

Prince and High Street intersection in Lancaster City shows off the new sidewalk and signage treatments that make navigating on foot much easier

Gay Street in downtown West Chester is sprinkled with restaurants, retail shops and sidewalk cafes

All photographs by BRAD BOWER