The EPA estimates 450,000 brownfields–abandoned gas stations, derelict mines, shuttered factories–litter the country. Contamination at such sites from trash, oil, or industrial activity won't make the Superfund list but does deter redevelopment and lowers property values even in otherwise desirable locations.

Pennsylvania has invested over $518 million to help 1,200 sites and retain over 87,000 jobs. The PA Department of Environmental Protection is collaborating with the Team PA Foundation to inventory brownfields and their characteristics to facilitate companies' finding sites that suit their needs. Nationally, EPA's brownfields program since its inception in 1995 has disbursed almost $900 million to reclaim 25,000 acres and assess another 16,000 sites.

Some brownfields, such as the former Bethlehem Steel mill, can stretch for miles. Others may cover only the corner of a block. By focusing on smaller sites in western Pennsylvania, the non-profit North Side Industrial Development Company strives to maximize its impact.

Assessment is Critical

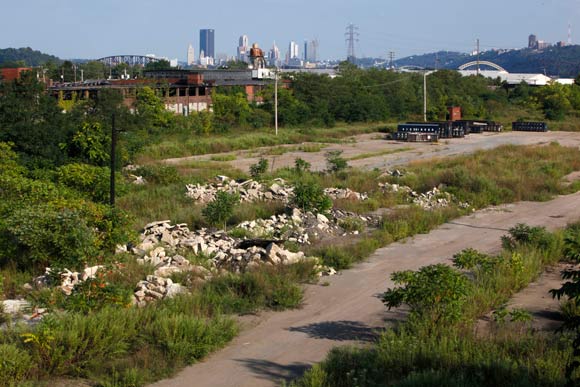

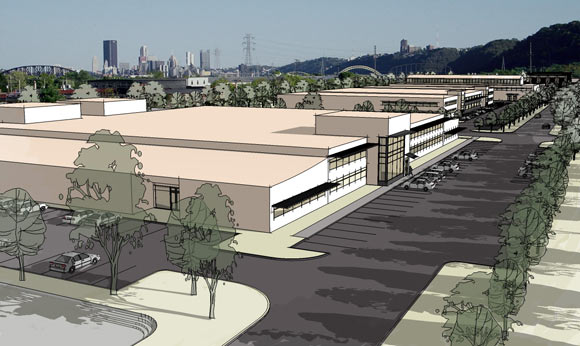

According to its executive director Emily Buka, NSIDC has received $3.4 million in EPA community-wide brownfield assessment grants. (NSIDC does business under the name the Riverside Center for Innovation.) The latest $1 million came in June, when NSIDC led a coalition of 20 municipalities along the Ohio and Allegheny Rivers to get funding to assess 52 acres of the former Pittsburgh & Lake Erie Railroad maintenance facility in McKees Rocks. The DEP, working with the Department of Community and Economic Development, also awarded money to redevelop the site, which is expected eventually to bring in $13 million in tax revenue.

Kevin Sunday, a spokesman for DEP, says that revenue is especially important where the per capita income is only about $13,000. “In this case, you're looking at a site that has a direct skyline view of Pittsburgh. Most former industrial centers are near urban areas and have the potential to revitalize a community. The brownfields program is a winning proposition both economically and environmentally.”

Even if relatively small, the P&LE site is the largest NSIDC has tackled. Its previous work included a half-acre gas station and 6-acre Henry Miller spring plant. Those sites, however, taught Buka that “the combination of riverfront properties, multiple municipalities, and economic development combined with brownfield redevelopment appealed to the EPA, so we took that model and recreated it. Ironically,” Buka adds, “the perception is that the riverfronts in Pittsburgh, PA, must be contaminated. There are some problems, but none of them are Love Canals.” Contamination at most sites can be cleaned or controlled relatively easily, improving NSIDC's bang for the buck.

The bigger problem, in contrast, can be getting property owners to agree to an environmental assessment in the first place. The P&LE site had been subdivided and sold to four owners. NSIDC had to get them all on board. Owners are Buka's top concern for any brownfield project: will they give outsiders access to the site, and will they use the assessment results? “We have to approach the property owners and convince them it's in their best interest to allow an assessment. People are reticent, afraid, especially when you bring up the EPA. But we've been very successful. We explain why if you don't do something now, you will have to do it later, and the property will be continually undervalued until you do.”

Big Payoffs, Few Tradeoffs

Redeveloped sites increase adjacent property values but obviously add more value to the former brownfield itself. In Lancaster Country, Franklin and Marshall College, local hospitals, and others came together to redevelop a former tile production site into a mix of academic buildings and athletic facilities. Also in Lancaster, an illegal riverfront landfill was reclaimed as a park and habitat for bald eagles. The Dark Shade Watershed project in Shade Township and Central City near Johnstown was the first EPA assessment grant awarded for mine-scarred land with the aim of attracting rafters, fishers, and hikers.

Once owners do agree to improve the site, NSIDC can provide further support. Although the P&LE site will be developed by an outside developer, the Trinity Development Corporation, “If we have a willing property owner who wants to expand business,” says Buka, “that can work just as well. We don't have to have a developer.”

As a certified industrial development company, NSIDC has access to favorable loans from the Pennsylvania Industrial Development Authority. It also has good relationships with banks and can package financing to follow a brownfield assessment.

DEP's Sunday notes that external support, including grants, can be crucial to enable property owners to rehabilitate a brownfield, especially one they can't sell. “A lot of the concerns are often aesthetic,” he notes, “but you do have environmental concerns, especially in industrial areas. At a certain point, it becomes prohibitive for the private sector to shoulder the cost alone, and government needs to step in.”

But with all the brownfields out there–136 alone in Washington County near Pittsburgh–NSIDC has to start small. Buka explains, “We go to the borough manager or the borough secretary and say, 'What do you got?' We don't do a site they don't want us to do. That's how we build up inventory.” Then they begin to woo the property owners. Even one lot can transform a street. By starting at that level, says Buka, NSIDC “can have a real impact. If you add up all we've done, we've had an economic impact parallel to larger sites.”

MARK MEIER is a writer, independent consultant, and part-time professor who lives in Dunmore and plants butterfly gardens in Scranton (which is his back yard). Send feedback here.

Photos of Emily Buka and Brownfield sites by Heather Mull

Renderings of Restored Historical Boiler & Tank Shop – Redeveloped P&LE Brownfield – McKees Rocks, PA (courtesy of Emily Buka)