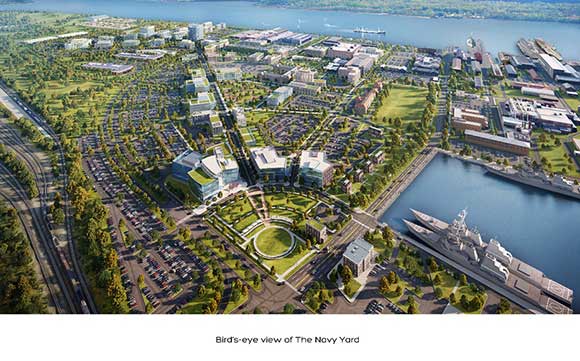

Imagine a waterfront urban space with its own electrical grid, its own street system and its own community of dedicated sustainability advocates. It would be the perfect testing ground for best practices in energy-efficiency and stormwater management — a real-time laboratory for smart grids, run-off canal systems, industrial reuse and cutting-edge new construction. It's already a reality here in Philadelphia.

Over the past decade, the Navy Yard has become a national hub for energy innovation and sustainability research. That reputation was solidified in 2011, when the U.S. Department of Energy committed $125 million to the creation of the Energy Efficient Buildings (EEB) Hub, now considered the nation's largest research center for the energy economy.

But the former Philadelphia Naval Shipyard gets far less attention for its unyielding dedication to stormwater management practices. Driven by its original 2004 Master Plan — and its location on the temperamental Delaware River waterfront — the Navy Yard has been a testing ground for Green City, Clean Waters, the city's comprehensive watershed protection and stormwater management plan.

In their role as master developer at the Navy Yard, the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC) has been a leading force in advancing these goals. They partnered with the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD) to implement their Green Streets initiative in the Navy Yard — a comprehensive protocol that included rain gardens along thoroughfares to assist in runoff from impervious pavements. It was the first program of its kind in the region.

“For years the Navy Yard has been a test bed for stormwater management practices in the region,” says Jennifer Tran, PIDC's marketing and communications manager for the Navy Yard. “What's been implemented here has been taken to other places [in the city].”

Those outside the area have taken notice, too.”Washington, D.C. is in the process of adopting a lot of [stormwater management practices] that Philly has already done,” says Tran. “The Navy Yard's been the test bed for much of that.”

Now, in a new Master Plan Update compiled by Robert Stern Architects (and released a few weeks ago), the Navy Yard's stormwater sustainability goals go even further, promising to raise the bar for how the region tackles watershed protection, runoff mitigation and sustainable site development.

Seeing Green

One of the most important tools for managing stormwater is absorption. Non-porous surfaces are the enemy, funneling water down streets and directly into overwhelmed waterways (and bringing residue, trash and toxins along for the ride).

To mitigate this problem, the Navy Yard's transformation includes various large green space projects: adjoining the main entrance is Crescent Park, completed in 2005; the Navy Yard Greenway, an $8.1 million one-mile long recreational trail along the Delaware River, was completed in late 2012; and construction recently began on League Island Park, a $2 million, 2.5-acre park designed by Philadelphia firms Wells Appel and KS Engineers that will employ stormwater management practices and wetland features.

And, later this year, the much anticipated open space designed by James Corner Field Operations – creator of the Race Street Pier in Old City and the High Line in New York City – is set to begin construction in the Central Green District (formerly called the Corporate Center) of the Navy Yard.

Building off the foundations set forth by its 2004 predecessor, the updated plan revises development and road layouts for the existing Central Green District and Historic Core District and reimagines a new Port Expansion area to the site's eastern edge.

But it's the plan's two new developments — the Mustin Park District and the Canal District — that have stormwater geeks most intrigued.

The projects feature innovative approaches. A large reflecting pond and canal system will act as a backbone to the new building-specific systems to be completed in the coming years. Those systems will feature green roofs, rain gardens, bio-retention and porous pavement.

The canal — a series of four pools separated by causeways — is at the heart of the new stormwater plan. The canal collects runoff, holds it, and provides a controlled access point directly into the Delaware River.

Directly north of the canal will be Mustin Park, an impressive seven-acre landscaped park built for recreation. Its rolling hills, athletic fields and reflecting pools are directly connected to the canals, funneling its own runoff into the larger system.

In each new development district, new construction buildings will be served mostly by surface parking lots, seen as unavoidable in the short-term due to the Navy Yard's poor transit access. To mitigate this potentially unsustainable development pattern, the parking lots are sloped to drain surface runoff into a system of greenways that run through each lot. The system will funnel runoff directly into the canals and mitigate potential watershed hazards.

Live/Work Balance

Of course, stormwater — and broader sustainability — practices are only part of a larger vision for the city's southeastern asset. Those priorities are elemental to branding the Navy Yard as a place for innovation, entrepreneurship and environmentalism. (As an indicator of that effort's success, PIDC recently celebrated the 10,000th job at the Navy Yard.)

Yet critics are quick to point out that the Navy Yard is still an office park, and not yet the cohesive mixed-use village planners envision. That goal requires a more ambitious integration of jobs, transit and residents.

Efforts to build a genuine neighborhood are underway. A Courtyard by Marriott hotel is set to open this fall and PIDC is looking for a restaurant tenant. According to Tran, the updated master plan still features a residential component — albeit downscaled due to the current economic climate — and (long dreamed about) plans for an extension of the Broad Street subway line. The plan also places a heavy emphasis on accommodating cyclists and cultivating pedestrian friendly streets.

The Navy Yard's longterm goals are lofty: 30,000 employees, 13.5 million square feet of commercial real estate and 1,000 residential units in the next 15 years. If all goes according to plan, this will be achieved in tandem with an equally impressive emphasis on sustainability that promises to elevate the conversation about how we manage stormwater and protect environmentally sensitive areas.

“Our next step is to manage the growth of the campus with this updated Master Plan,” says John Grady, president of PIDC. “[We are] providing a blueprint for the continued development of the Navy Yard as a vital economic engine for the city and region, as well as a leading demonstration ground for the nation.”

GREG MECKSTROTH is Flying Kite's development news editor.