Philadelphia has 40,000 vacant lots. Alex Gilliam, an architect, designer and University of the Arts professor, sees opportunity in those empty spaces — a “classroom for the 21st century.” For the past decade and a half, he's taught urban youth in Flint, Michigan, Chicago, the Bronx and Philadelphia to remake crumbling spaces in their neighborhoods, be it an abandoned lot or an aging school.

This past July, he launched the Tiny WPA, an outgrowth of his design consultancy Public Workshop.

In just a few short months, Tiny WPA — think Roosevelt's Works Progress Administration, but for smaller urban projects — has completed four projects in three cities. In Philly, they engaged 70 local youth and college students to create a pop-up playground in Rittenhouse Square, partnering with the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society and Design Philadelphia. Tiny WPA has also attracted attention in Germantown by collaborating with the Village of Arts and Humanities on a shade canopy, made from 1-by-2-inch wood planks, for the youth permaculture group Earth Philly.

Recently, the budding nonprofit was awarded a grant from the Delaware Valley Green Building Council (DVGBC) to revitalize Smith Playground in Fairmount Park. The outdoor space, which will serve as DVGBC's Greenbuild 2013 legacy project, will double as a green building workshop.

Of course, involving underprivileged kids in urban transformation is nothing new, but Gilliam maintains that his work is not charity or some “hippy-dippy” attempt to change things. Good design, he says, is informed by the user. Sometimes, those users are children.

“I'm not interested in creating another youth program,” he says. “I'm interested in finding those needs in the cities where youth and/or multi-generational teams are the highest means to solve that problem — and then letting them have at it.”

This has included encouraging kids to build air and water quality sensors that measure the “health” of their schools, gather multi-generational stories on their neighborhoods, or imagine new play places made of wood boards and rope.

The hallmark of Tiny WPA, says Gilliam, is taking the design process out of the studio and onto the sidewalk. Starting with materials like packing tape and cardboard, students are asked to build, revise and rebuild to-scale play structures until they become usable designs. This rapid prototyping — which Gilliam refers to as “academic gym” — stimulates collaboration, negotiation and team work, skills generally not part of the middle and high-school curriculum.

“Instead of using pencil and paper, we use wood,” says Gilliam. “When someone can get inside, when they can feel it, when they can touch it, then they're able to participate a lot better.”

Gilliam, who was raised in Charleston, Va., began working in Philadelphia in 1998. Less than two years after graduating with a BS in architecture from University of Virginia, he was hired by then-brand-new Charter High School for Architecture and Design (CHAD) established by American Institute of Architects.

The experience was a startling introduction to Philly's education system, but it was also an opportunity. At 23, Gilliam established himself as chair of CHAD's design program and helped create the school's first architecture and design curriculum.

Years later, in 2004, Gilliam's four-month fellowship with Auburn University's Rural Studio solidified his theories on youth design and project-based learning. The program took him to a dilapidated high school in a remote section of Alabama with less than 400 students.

Although the principal encouraged him, most of the teachers were skeptical that anything could change. With two digital cameras, Gilliam helped students collect images of broken bleachers, chipped walls, crooked doors and other physical details that troubled them. In small groups, students analyzed the pictures, determined what needed to change and identified the people who could help. The process was repeated until the entire student body had developed a plan.

“You were able to see what consensus was,” says Gilliam. “I learned that if I was actually able to give kids control of the world around them — which is the fundamental human desire, especially the fundamental teenage desire — pretty cool things start to happen.”

Although their original priority — building a ticket booth for football and basketball games — never came to fruition, the students were able to repaint 37 doors as well as the entire gym, fix the bleachers, replaced windows and create six murals. At the end of Gilliam's fellowship, teachers noticed students behaving differently and there were fewer in-school fights.

“Three months into this project I was really frustrated because we hadn't really gotten into much design,” explains Gilliam.

“But I stepped back at a certain point and realized it didn't matter. I created a really simple process that empowered the kids to decide what they wanted to change in their school.”

In 2009, after gaining a masters in architecture from the University of Texas, Gilliam returned to a changed Philadelphia. Yes, the city still had vacant lots, crumbling schools and inefficient city departments, but, as Gilliam notes, Philly had gained a progressive mayor, a forward-thinking water department and experienced its first population bump in 50 years.

“For the foreseeable future, Philly is where I want to be and have impact,” he says. “There's this wonderful mix of opportunity and need. It's one of the best testbeds I can imagine.”

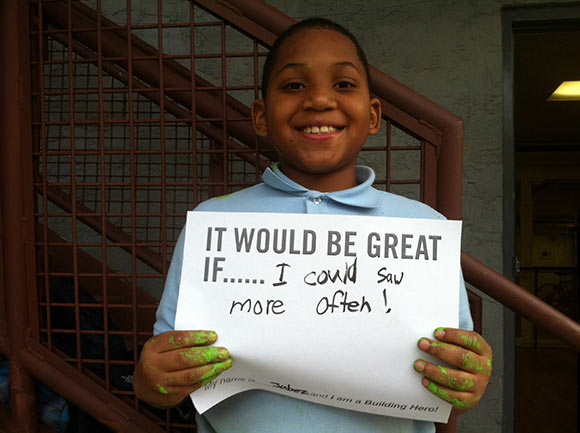

Tiny WPA provides direct skill training, including math, social skills, the use of power tools, and the collection and analysis of data. More importantly, says Gilliam, people from the community approach young people to ask questions and congratulate them, breaking down stereotypes of the “vilified” teenager. “In the context of school they never get that kind of attention,” he says.

The organization's current work is based on “adventure playgrounds,” a concept from Post World War II Europe, where kids built impromptu play structures from scrap wood, rope and spare tires in bombed-out lots. Eventually, the activity became a movement, and over 1,000 of these play spaces remain throughout Europe.

Gilliam believes the same phenomena could happen in public schools where overcrowding, structural damage and the heat-island effect creates an unhealthy habitat. He hopes to bring Tiny WPA and youth-led design to ten Philly schools over the next three years. He also aims to establish a feeder program that enables emerging Tiny WPA leaders to spread the philosophy and spearhead projects in their own neighborhoods.

As for the Smith Playground project, slated to begin in late spring, Gilliam says the need for change is evident in its current patterns. The space, the second oldest playground in America, has been well worn outside of the designated play spots.

“I don't believe that youth can do everything,” he says. “But they are experts in their communities and in their own lives. So, why not leverage that into something?”

DANA HENRY is sister publication Flying Kite's Innovation & Job News Editor.