“When I grow up I want to be a geospatial technological engineer.”

There’s a phrase you don’t hear every day, which is why Professor Albert Sarvis of Harrisburg University of Science and Technology is keen to spread the word about the grant he received to oversee part of a $1.6 million mine mapping project for the commonwealth’s Department of Environmental Protection Bureau of Mining Programs.

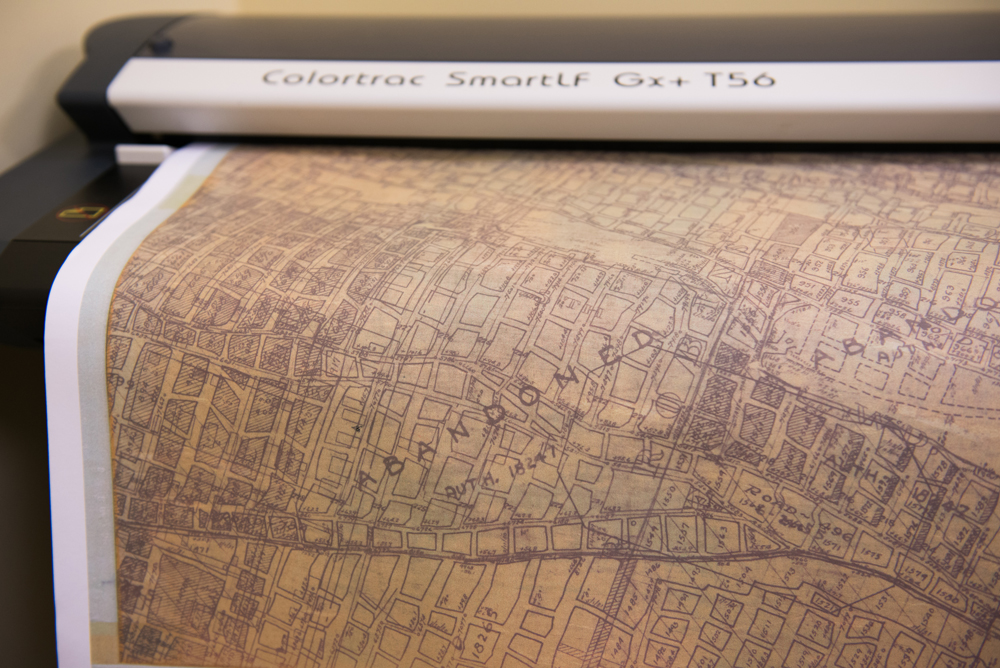

This fall, students in HU’s undergraduate geospatial technology program will partner with peers in the school’s graduate-level project management program to commence work on a three-year initiative to scan, validate, and electronically archive maps of both active and abandoned Pennsylvania coal mines.

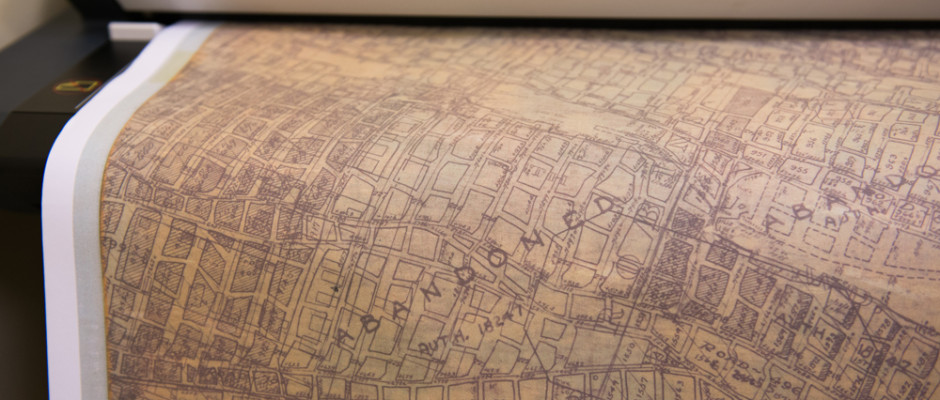

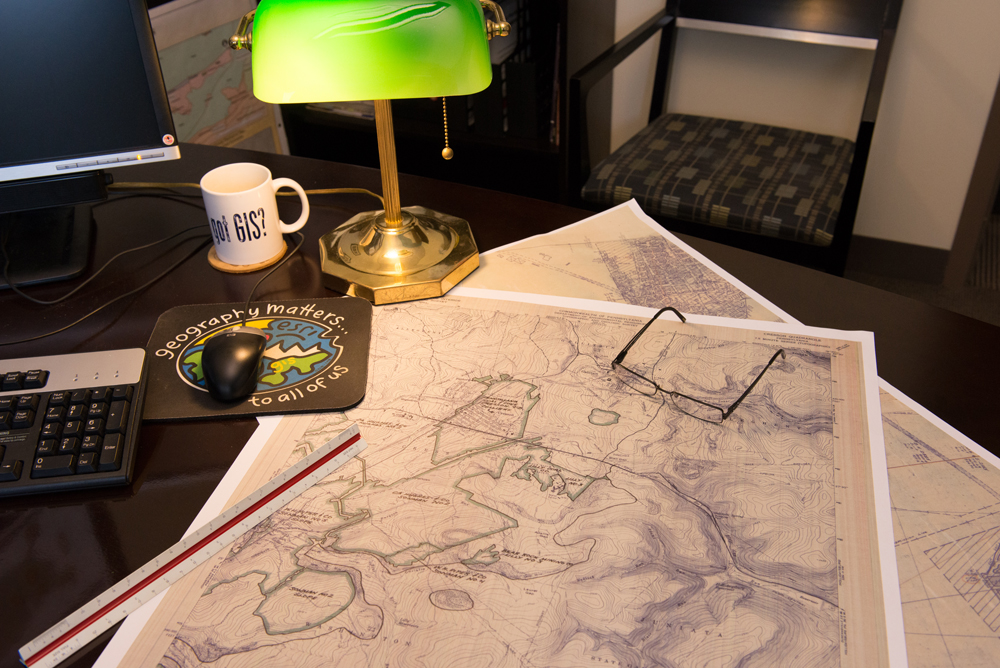

According to Larry Ruane, a mine subsidence insurance administrator with the Bureau of Mining Programs, the primary goal of the grant is to modernize DEP mine mapping operations by converting more than 15,000 existing—and in some cases deteriorating—hard copy maps and images into digital format for use in computer applications, particularly geographic information systems (GIS).

The end goal is to enable the DEP as well as the general public to more quickly and accurately access mine information the same way people now use Google to look up street maps. In the case of mine maps, however, the more compelling case for accuracy and expediency is the benefit to life and property that electronic records stand to provide—in case of mine safety events for example, such as guiding aid to trapped miners, or assessing the risk of subsidence to structures or development plans.

Funding for the project comes from state proceeds authorized by legislation addressing mine issues like reclamation, conservation, safety, and subsidence. But two key stipulations of the grant will help ensure direct returns on the commonwealth’s investment: a requirement that grant recipients be either state educational institutions or nonprofit agencies, and also emphasis on the Commonwealth Investment Criteria, which seeks to increase job opportunities and foster sustainable business in PA.

“By partnering with universities and nonprofit entities in the state, DEP is facilitating the advancement of GIS technologies that have a broad application in the 21st century workplace,” says Ruane.

In places like Harrisburg U., the grant will directly help educators like Professor Sarvis develop facilities and curriculums that provide highly sought, hands-on training and real-world work experience in both growing and emerging technological fields.

Poised to celebrate only its eighth year in operation, Harrisburg University bills itself as the first private, science- and technology-focused, not-for-profit university established in Pennsylvania within the past 100 years. The school offers six undergraduate and four graduate degree programs, all targeting career-focused STEM disciplines, and all with close ties to key PA industries.

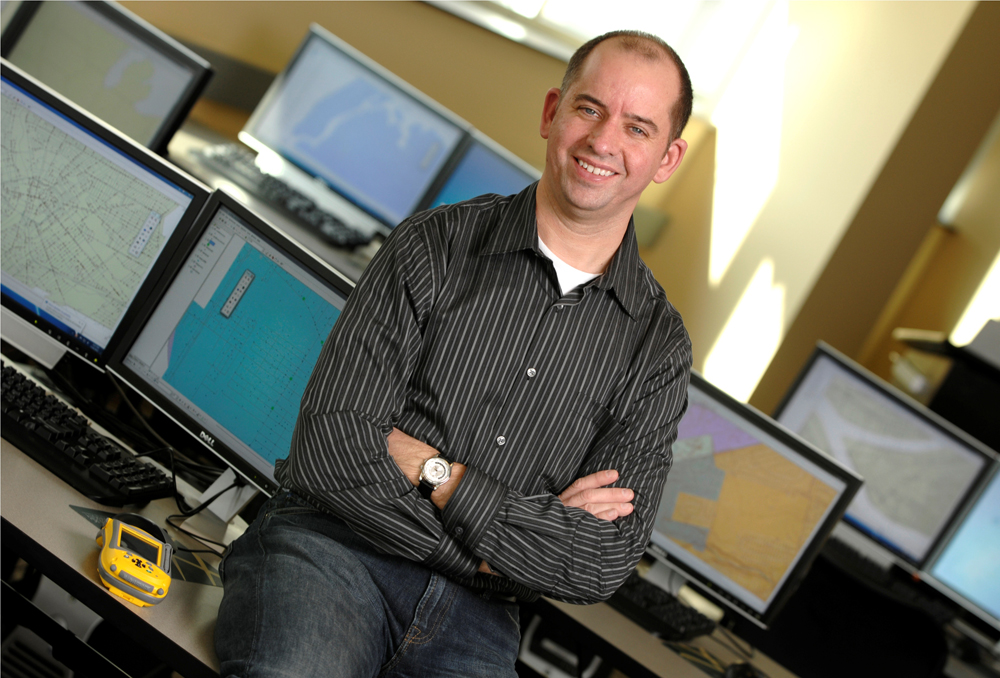

Sarvis is an assistant professor of both geospatial technology and project management. He also serves as director of both programs, both of which he helped develop. In the realm of mapping, his previous experience includes work for the U.S. defense industry and both private and civil government projects, including coastal mapping.

“It’s a way of analyzing information that applies to nearly any industry or organization,” says Sarvis, explaining just what it is that people in his line of work do.

“Eighty to ninety percent of all data has a spatial component. The ability to locate information—to provide details about not only the feature on the surface of the earth, but also its precise location—those things combined sort of form a framework for accessing and analyzing information.”

The City of New York, for example, uses mapping to track hospitalizations for severe asthma attacks, noting details down to the level of individual community districts.

“We can map those rates across the relevant geographies to look for patterns and establish analysis baselines based on distribution of information spatially,” says Sarvis

For students more inclined to study the technical side of the career field, Sarvis says geospatial technologies encompass the sophisticated tools used to perform mapping—quite literally on a global scale—things like global positioning systems (GPS); remote-sensing aerial, satellite, and photographic technologies; and finally, geographic information systems themselves, used to store, manipulate, and analyze data.

Helping students understand the context—the multitude of ways that mapping tools and technologies can be applied, in any number of fields—is both a great challenge and a great thrill for Sarvis, who views the mine map grant as an experiential windfall for his students who will commence working on the project in September, with the start of the new academic year.

“When they finish they’ll have nearly 2,000 hours of experience on this project,” he says—the equivalent of nearly a full year of on-the-job training. “I’m also hoping it will be attractive to students who are considering the program but don’t know much about it.”

Courtney Koch is one such student. The 19-year-old from Jersey Shore, Lycoming County, is about to commence her sophomore year at HU. She plans to major in both geospatial imaging technology engineering and computer security. But the self-professed “really good soccer goalkeeper” admits that neither HU nor geospatial technology were on her radar screen just a few short years ago.

“I thought that I was going to go to a big Division I school and play soccer. Then I got into a car accident, and I broke my back, and I was like, ‘What am I going to do now?’”

The answer came after Koch won a scholarship to Harrisburg University, looked into the school’s geospatial technology program, and fell in love with the field.

“I’ve always wanted to be an FBI agent, and this a way to get there. I love that I can pull up a map and find out everything about an area’s location. It also goes along with computer security,” says Koch, her enthusiasm nearly palpable.

“We’re a small school. As sophomores—there’s only eight of us in geospatial technical engineering—we get a lot of one-on-one time with Professor Sarvis. When you do all these exciting projects, it makes you excited for your future. It makes you want to go out and be like, ‘What else can I do with mapping?’”

For Koch, the chance to gain actual work experience providing tangible project deliverables to an end-client agency like the DEP is invaluable. The opportunity to earn a little money for something she’d be studying anyhow is gravy (courtesy of funding allocated through the grant). But the real prize is the science, technology, engineering, and math education that she views as the key to her future—a perspective shared by her professor, her university, and the DEP, as evidenced by the department’s commitment to directing grant funds for the mine map project toward schools like HU.

“STEM schools are meant for you to succeed,” says Koch. “And that’s important for me to be able to graduate and know that I have all the things that I need to be successful in life.”

MARK KENNY is a Pittsburgh-based features and business writer. Send feedback here.