Philadelphia's ongoing struggle with vacant land is getting lot of attention this year. Councilwoman Maria Quiñones-Sánchez's effort to get land bank legislation through city council recently cleared its committee hurdle in front of a packed house. (The legislation is meant to make it easier for the city to obtain parcels of tax delinquent land while simplifying the process of purchasing publicly-held blighted property.) The consensus number of vacant parcels in the city is 40,000, with roughly a fourth owned by various city agencies and three-fourths by private citizens. That's not much when compared to Detroit’s 100,000 vacants, but these properties leech from public coffers (about $20 million a year), while adding nothing to the tax base and serving as hotspots for illegal dumping and other crimes.

But amid all the discussion of land use policy and council politics, it's worth pausing to remember what many of these lots used to contain. That's the contention of Temple Contemporary's “Funeral For A Home” project, an art-advocacy hybrid that hopes to both inspire a remembrance of Philly's past and a vision for the future of these neglected spaces.

“One out of every ten homes in Philadelphia sits vacant,” the website reads. “Despite the first rise in our city's population in sixty years, we still have more houses than people to fill them.” The city hit its peak population of 2.1 million in 1950, and even the most fervent urban booster wouldn't predict a return to that concentration. Empty old houses, slowly crumbling, are demolished by the city at the rate of more than one per day (according to the Department of Licenses and Inspections over 500 are leveled each year) and the number of private demolitions and unforced collapses is not tallied. This grim process goes largely unnoticed.

Funeral for a Home is a multi-faceted project, including elements of oral history and community engagement, but its climatic moment will be a public memorial service held this spring right before a row house is brought low. The exact address of the (ex-) home in question has not yet been released, but it is located in the Mantua neighborhood of West Philadelphia. A team consisting of artists, historians and architects is gathering stories and data from the surrounding neighborhood and trying to track down relatives of old inhabitants.

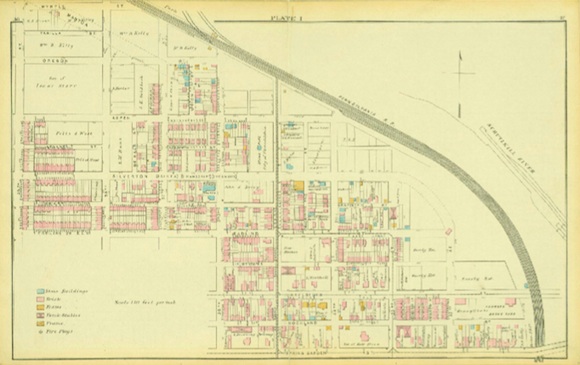

“The house we are working with was built in the 1920s,” says Patrick Grossi, project manager and local historian. “There are three vacant lots to the west, two empty lots to the east and a considerable number on the other side of the block. The block has lost a lot over the years. If you look back at the Philly Atlas, [as far back as the 1870s] you already see a fully completed block. That's part of the value of the project — to pause and take stock of what has been lost.”

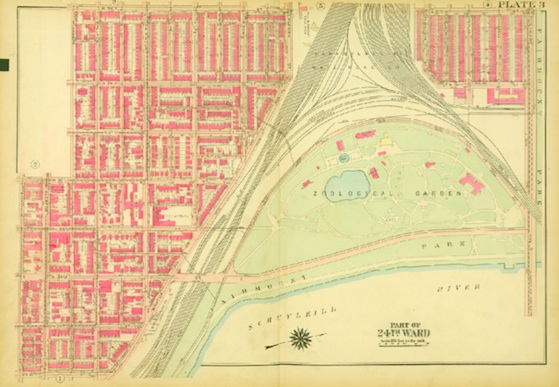

Mantua is a neighborhood on the western side of the Schuylkill River, to the north of Drexel and the University of Pennsylvania. Unlike, say, Kensington or South Philadelphia, the neighborhood was never home to much industrial activity. When the house in question was built, the area was predominantly Irish and Jewish. By the 1960s, it was mostly African-American and still is: Census Tract 108, where the house sits, was 96 percent African-American according to Census data from 2005-2009. The neighborhood's housing stock changes block-to-block — one street may be full of gaping empty lots, another is without a single vacant. The neighborhood's southern borders are undergoing gentrification as Drexel University students move northward.

“The timing of this is really special: We are on the edge of a whole different kind of community than when I first moved here,” says Gwen Morris, board member of the Mantua Civic Association. She has lived in the neighborhood for 42 years and reports that her block, which used to be occupied entirely by families, is now heavily populated by an ever-shifting student population. “The older residents feel that new development and all the new stuff that is going on in Mantua, you just don't want to lose the sense of who you were. One of the board members used to play with the two little girls who used to live in that house.”

Mantua wasn't the only option, of course. Grossi, Billy Dufala (his brother Steven is also working on the project), and Temple Contemporary director Robert Blackson spent the entire summer searching for an appropriate location in Kensington, North Philadelphia above Girard, and the neighborhoods around Temple's campus. They were looking for a house that was clearly beyond repair, had an owner that was willing to work with them, and was located in a neighborhood with strong, planning-minded community groups.

Although they initially focused their attentions on Kensington, Billy suggested Mantua (which is just to the north of the hulking warehouse where his collective, Traction Company, operates). The neighborhood's long tradition of civic advocacy, from the 1960s-era Young Great Society to the Mantua Community Planners, who formed to resist top-down “revitalization” strategies in the 1970s, sold the rest of the group. The Temple team is working with the Mantua Civic Association, the Mantua Community Improvement Committee, the People's Emergency Center CDC, and Mt. Vernon Manor, Inc. an affordable housing apartment complex in the neighborhood.

Like much of the city's housing stock, the deceased is a row home. Block upon block were erected during the city's heyday. In 1950, at its peak population, only 15 percent of Philly's housing was fully detached, compared to 20 percent in New York, 28 percent in Chicago, and two-thirds in Los Angeles. According to Funeral for a Home's website, from 1863-1893, “these homes shot up at a rate of nearly ten per day.”

Funeral for a Home won't just focus on one hollowed-out house. Grossi is conducting a series of interviews with neighborhood residents in the months leading up to the ceremony. He wants to capture a sense of the neighborhood's continuing evolution in the words of residents.

The group is also trying to secure maintenance and future plans for both the place where the house now slumps and the rest of the block. The Pennsylvania Horticultural Society has agreed to maintain the lot after demolition and West Philadelphia Real Estate, the owner of the lot, has committed to erecting a row of affordable housing on the block within a year of the public memorial.

The ceremony itself it still taking shape. The rite is meant to culminate in “collaboration with a demolition crew in the razing of the home.” The idea is to give the home a respectable end, with music, accompanied by testimonials from past owners (who Grossi is tracking down), neighbors, and Funeral for a Home representatives.

The deadly collapse of a Center City building in June altered their original plans. The team had initially hoped to work with the Department of Licenses and Inspections to obtain the desired property, perhaps on one of the city's 10,000 parcels. But after the June tragedy, Grossi and his colleagues decided to work with private owners instead, fearing that the city would be leery of letting anyone near their demolition work.

Funeral for a Home also has to deal with a perennial Philadelphia issue: Racial segregation. All of the project partners are white, while the community representatives they are working with, and the community itself, are mostly black. Grossi hopes that Mantua's assertive community groups will keep his work honest.

“This is a huge question for public history because public historians tend to be white, but the areas they engage with tend [not to be],” says Grossi. “There can be almost this colonial model where white professionals are coming in and demonstrating how work should be done and the groups they are working with have to follow suit. [We're trying] to recognize [race] up front and come up with a different model, one in which [community members] are active participants. Due to the organization's vibrancy, there are opportunities here to engage the story of a particular group of people in a particular part of town.”

During Grossi's initial presentation of the proposal to Mantua Civic Association, President Dewayne Drummond reminded Grossi of another danger: Sentimentality. Rose-tinted glasses never helped anyone but their wearers.

“I need you to promise me to make it real,” Drummond told him. Funeral for a Home has six months to figure out what that means and, then, respectfully, put a Philadelphia home to rest.

JAKE BLUMGART is a writer and editor based in Philadelphia. Follow him on Twitter.