Beer — and excitement — is brewing in Pennsylvania, where the craft beer craze that has swept the nation is finding a home in the factory spaces industry left behind. It seems that every day a new small brewery is opening, serving signature beers to a public whose thirst cannot be quenched.

There were 88 breweries in the state in 2011, but by 2013, the Brewers Association counted 108, producing 1,788,556 barrels of craft beer (second only to California). The association defines a craft brewery as one that is at least 75 percent independently owned and produces fewer than six million barrels of beer annually.

In western Pennsylvania, craft brewers say the scene is still in its infancy, leading to a more homespun and collaborative take on production.

“It's never anyone saying it's us versus anyone else in the city,” says Greg Hough, who runs the state's first brew-on-premises establishment, Copper Kettle Brewing Company, with brother Matt Hough. At Copper Kettle, patrons can brew and bottle their own cases of beer. In addition to teaching brewing skills, Hough sells supplies to home brewers, some of whom got their start at Copper Kettle.

“Sometimes they come in and bring us samples of what they've made at home,” he says. “So that's always nice.”

The brewery is connected to Hough's Taproom & Brewpub. The idea was born when the brothers saw interest in the process behind the craft beer they were serving.

“Brewing can be intimidating if you're doing it by yourself,” explains Hough. “We take the guess work out so you can brew without fear.”

The brothers were able to purchase and refurbish six small brew kettles, and today, they teach curious customers to brew, adhering to over 50 tried and true recipes. The kettles in the storefront shop bubble, hops and grains line the brewery's shelves; the place is warm, its smells yeasty and comforting. Drums of tasty beer malt sit ready for service and brewmaster Ben Minden asks today's eager neophytes if they want to taste the sweet sticky substance.

“I once made an ice cream sundae with this stuff and garnished it with the grains we use. It was delicious,” he recalls.

One malt tastes like Raisinets, the other one is better than chocolate syrup and leaves a wispy strand of sugar trailing behind each drop like a sticky spider web. The couple in charge of this batch pour the gooey mixture into the copper kettle and then wait 18 minutes, retreating to the Taproom for a tipple.

When the Copper Kettle isn't cooking beer for guest brewers, it's brewing up Hough's Belgian tripel or its Cuckoo Clock of Doom, a double IPA.

“If you are looking for the people who are making great strides in brewing, it's the craft brewers, not the big companies,” explains Minden. With that, it's off to The Brew Gentlemen Beer Company to meet Braddock's barely legal brewer.

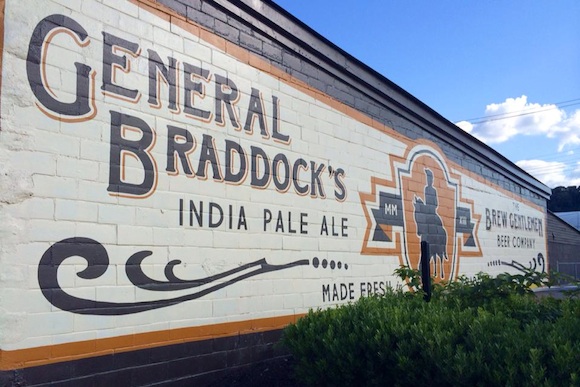

Brandon Capps is 22 years old and sporting a Georgia Tech t-shirt. He just moved to the area from Atlanta for this job. It's a Thursday and the brewpub — located outside of Pittsburgh in a post-industrial town that has garnered a lot of attention both for its struggles and its innovative redevelopment work — is full of patrons trying its latest creations. Capps enters their midst with a bag of pink peppercorns, the secret ingredient for tonight's hit, and invites customers to try them raw. They are sweet, smoky and delicious.

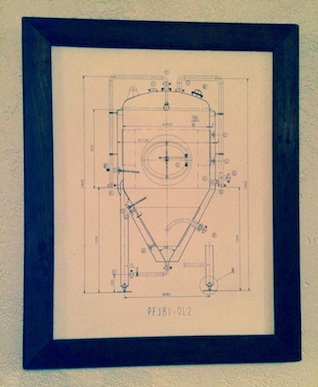

“I was munching on these all night when I was making this beer,” says Capps. A trained electrical engineer, he fell in love with the technical aspects of beer production and has built his own hi-tech homebrew kit in the back of the brewery to test recipes.

“I thought the science and art of making beer was really fun,” recalls Capps. “Turns out that drinking it is also enjoyable.”

Though Capps is young, he has already developed a following. Asa Foster, a Carnegie Mellon University grad and 24-year-old co-founder of The Brew Gentlemen praised his talents.

“Brandon can build a recipe and know what it will taste like without even having to try it,” he says. “We brought him up for an interview and he brought a liquid resume with him. It was very good. We've only dumped one batch of beer so far and that was ultra-experimental.”

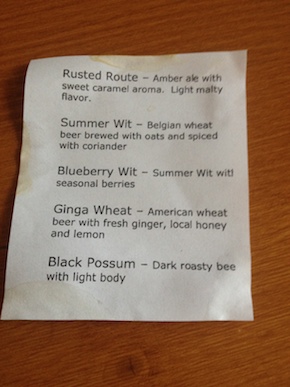

The Brew Gentlemen team insists that the only downside to being part of an adolescent beer scene is that experiments are sometimes not well received. Breweries are often trying to convince Bud Light drinkers to taste beers with names like Apple Pie or Black Possum, and that can be challenging. Capps is currently working on a recipe called “Beer,” to cater to more generic tastes. He wants to offer something for everyone, but also encourages customers to keep an open mind. He recommends trying brews with more complex flavors — such as sour beers — three times.

“It's like walking out into the daylight,” he explains. “At first it hurts your eyes, then you adjust. Then you realize, hey, it's pretty nice out here.”

Regardless of what they serve, every brewery visited on this trip had plenty of customers stopping in for a drink or filling up a growler. Some brewers said this was in part due to the commonwealth's unique liquor laws: small quantities of beer can only be purchased in certain stores, making the idea of buying a jug of beer from a local brewery more appealing. And while restaurants and bars must purchase expensive licenses to serve alcohol, breweries and distilleries just need to file the correct paperwork in order to serve their products.

“A lot of things people complain about are hugely advantageous to brewery taprooms,” adds Capps.

Grist House Brewing in Millvale was packed, serving customers its own brand alongside local wine and Arsenal Cider, fermented in a townhouse in the Lawrenceville neighborhood of Pittsburgh. Roundabout Brewery and East End Brewing Co. (which shares its space with Commonplace Coffee Co.), also had their fair share of customers when we visited. East End was featuring a coffee stout made using Commonplace's beans.

At Hop Farm Brewing Co., also in Lawrenceville, they grow hops in a partnership with Soergel Orchards in nearby Wexford. “We aren't growing all our own hops yet, because it's just not possible,” says employee Adam Kubala. “But it's something that the founder Matt started doing before he even opened the brewery — the plants take two to three years to mature.”

According to suds aficionados Grace Miller and Mark Turic, more breweries opening up just means more good beer. The pair's first annual Beers of the Burgh festival showcased all that local talent.

“In Pittsburgh, there are cideries and gluten free breweries,” says Miller. “You are getting a lot of different styles that you wouldn't see in other cities.”

Gluten-free brewery Aurochs Brewing Co. impressed festival patrons — they came with their own separate cups for people who suffered from allergies.

“There were a number of people who tried it and they couldn't even taste the difference between their beer and ones with gluten,” recalls Miller.

The festival sold out, hosting 1,000 drinkers, far surpassing organizers' expectations. Area restauranteurs also expressed their excitement at having so many local choices for their taps. Participating breweries all came from within 100 miles of Pittsburgh; even in suburban areas, breweries are popping up like wild flowers.

Jaime Rice, co-founder of one of Pittsburgh's newest breweries, Milkman Brewing in The Strip District, said the proliferation is purely positive.

“On the competitive side, it's just that we all need to make better beers,” he says. “There's not going to be any room in the market for sub-par beer, and that's a good thing.”

Rice started off as a home brewer, and he and his partners still have full-time jobs. He works as a software engineer and his girlfriend Brigid Estes, who helps him work the hand-carved taps, is a nurse; another partner is a chef. Estes says she had no interest in beer before Rice got her involved. Now she is slight more invested, having recently given birth to the couple's twins: Skout and Brewer.

Rice came to Pittsburgh from Albany, N.Y., eight years ago because he liked the city's wild yet laid back vibe: “If you don't like Pittsburgh, you haven't been here,” he exclaims. The building Milkman calls home will eventually also feature a winery and distillery, making it a one-stop-shop.

“I think Portland was going in the direction Pittsburgh is going now,” he explains. “What we are doing with craft alcohol is on trend with what we are doing here with food — they are working together.”

Fortunately, local politicians are supportive of these small businesses. “Mayor Peduto is a real person,” adds Rice. “You can even go have a beer with him, if you know the secret bar.”

ELIZABETH DALEY is a New York City native and freelance writer who relocated to Pittsburgh in search of a better life. Her work has appeared in USA Today, The Christian Science Monitor, Reuters and numerous San Francisco Bay Area publications. She is the innovation editor of Pop City. Follow her on twitter @fakepretty.