In the Lehigh Valley, a cavernous, century-old Bethlehem Steel facility once again brims with the mighty machines that transformed a young, agrarian nation into an industrial powerhouse.

The National Museum of Industrial History, an affiliate of the Smithsonian Institution, opened in August. According to Andria Zaia, the museum’s curator of collections, the goal is to “forge a connection between America’s industrial past and the innovations of today by educating the public and inspiring the visionaries of tomorrow.”

“American entrepreneurs, financiers, workers, engineers, scientists and inventors made decisions and took risks to advance American industry,” she adds. “Their actions affected economic, social, cultural and political growth. Industrial enterprises led to an increasingly diverse nation and workforce, with waves of immigrants from around the world and women drawn to the opportunities that large-scale industry provided.”

To tell that story, the museum focuses on several emblematic aspects of the nation’s — and Pennsylvania’s — industrial history. Centennial Hall displays 21 artifacts originally seen at the 1876 Philadelphia Exposition, which drew 10 million visitors to gape at the United States’ progress. The Iron and Steel Gallery showcases Bethlehem Steel. Other galleries are devoted to the Lehigh Valley’s silk industry and to the development of propane in Pittsburgh.

The museum is housed in a 1913 Bethlehem Steel electrical repair shop that Zaia says is “itself one of our most important collection pieces.”

Bethlehem Steel operated from the Civil War until the late 1990s, employing 31,000 people at its peak. When it closed, it became the largest brownfield site in the country. Today, the museum — along with the SteelStacks cultural campus and the Sands Bethlehem casino — is part of a massive reclamation and redevelopment program.

First proposed in the 1990s, the museum was sidelined by a grand jury investigation that ultimately found no criminal wrongdoing, but resulted in a 2015 legal order to open in two years or dissolve.

American entrepreneurs, financiers, workers, engineers, scientists and inventors made decisions and took risks to advance American industry.Andria Zaia

Philadelphia’s Metcalfe Architecture & Design was brought in, along with interpretive planner Rosalind Remer of Drexel University and New Jersey fabricator Art Guild, and given nine months to develop, design, fabricate and install the exhibits, a process that Metcalfe partner and design project manager Aaron Goldblatt says would normally have taken three years. He credits his colleague Jason Manning (the team also included Carol Huang and Katy Blander) for designing a a theatrical visitor experience and creating views of some artifacts from above, all while insuring accessibility.

Those artifacts are stunners.

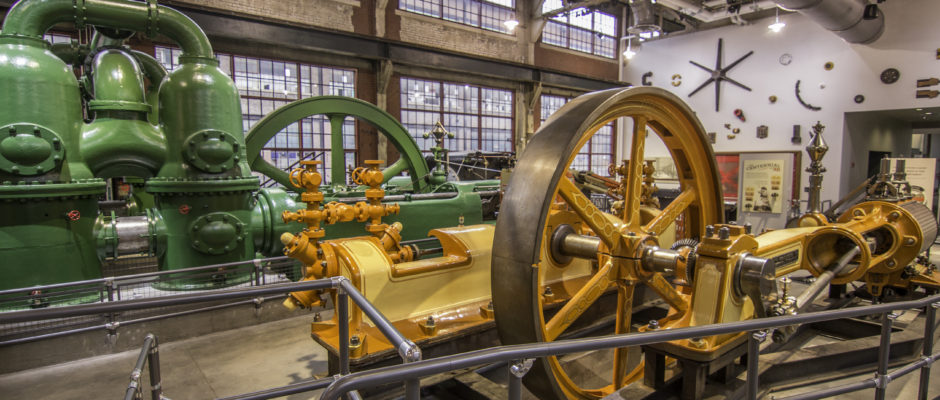

Zaia considers the 1914 Corliss Steam Engine a star of the museum; Goldblatt calls it is a “massive piece of equipment and gorgeous.” Used by the York Water Company, it pumped eight million gallons a day to supply 100,000 residents with water until 1956 and was on standby until 1981. In 1972 when electric pumps failed during Hurricane Agnes, it kept the city supplied with water.

The 1884 Linde-Wolf ammonia compressor is the oldest surviving refrigeration compressor. It used compressed ammonia to provide refrigeration, increasing production at Baltimore’s American Brewery from 40,000 to 100,000 barrels of beer a year. Like much of the 19th century equipment on display, it is highly ornamented and personalized, a craftsman’s touch that vanished in later decades.

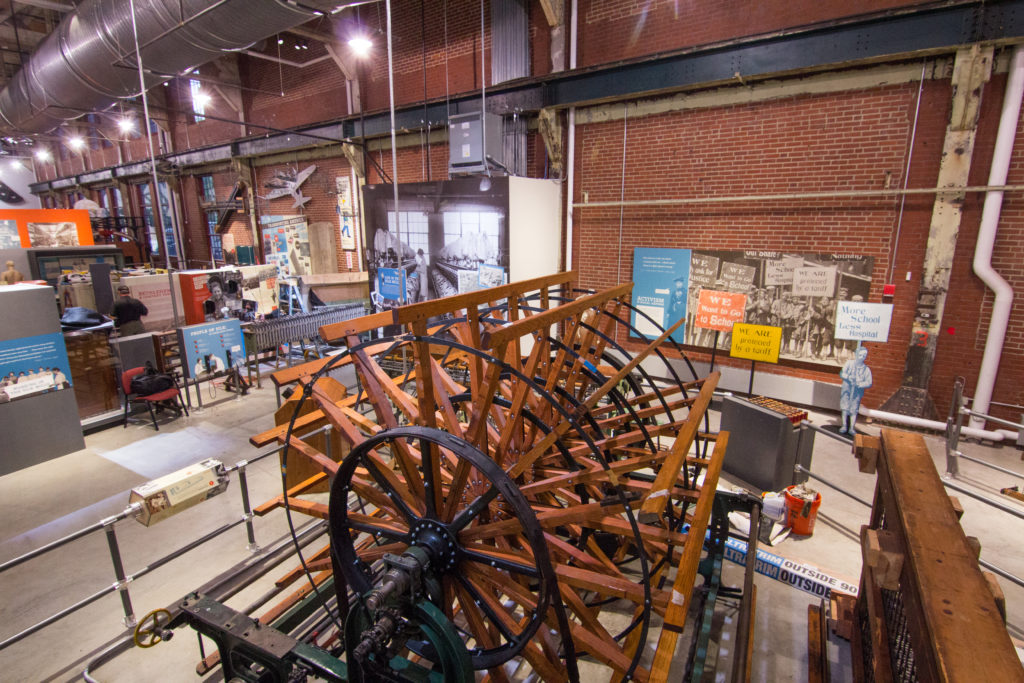

A line shaft is also on display. This sometimes-treacherous system of leather belts, pulleys and gears connected to a single power source drove multiple machines.

“A common industrial accident was somebody losing an arm to these belts that were utterly unguarded,” notes Goldblatt.

While men toiled at the steel mills, thousands of women and children worked at the silk mills. The Lehigh Valley’s silk industry, which boomed in the 1880s as New England and New Jersey silk manufacturers relocated for inexpensive labor, was the second largest silk-making region in the country by 1900, with 74 mills in Lehigh and Northampton counties alone.

The museum features looms, murals and machinery; some of it was used for Jacquard weaving, including the early-20th-century loom used by Scalamandré for Jacqueline Kennedy’s White House.

The museum features looms, murals and machinery; some of it was used for Jacquard weaving, including the early-20th-century loom used by Scalamandré for Jacqueline Kennedy’s White House.

Meanwhile, the Propane Gallery tells the story of how Walter O. Snelling, a Pittsburgh chemist, discovered and commercialized propane as a fuel in the early 20th: Snelling’s laboratory equipment and early canisters are showcased.

A rotating schedule of special exhibits is planned for next year, including a commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the “E” for Excellence Award given by the Navy to a Bethlehem Steel Plant in 1941. Over 37,778 ships for both American and Allied forces were built, reconditioned, repaired and modernized there for the war effort.

The museum is also at work to fulfill its mission of inspiring innovation. Zaia cites a recent collaboration with a product design class from Lehigh University to imagine unique products for the museum shop. During the semester-long project, students designed, prototyped, tested and manufactured their items with the museum visitor in mind. Proceeds from sales benefit both the museum and the young innovators.

That attention to the future is integral to understanding history, adds Goldblatt.

“My feeling is that history is not about the past,” he says. “It’s about how we see our own future. We selectively capture things that happened in the past to inform us about who we are right now and who we want to be. That, to me, is what history is.”

The National Museum of Industrial History (602 E. 2nd St., Bethlehem) is open Wednesday through Sunday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Admission: $12 adults; $11 seniors/veterans/students; $9 youth (ages 7-17); free for kids under 7. Contact: (610) 694-6644, info@nmih.org.

ELISE VIDER is news editor for Keystone Edge.