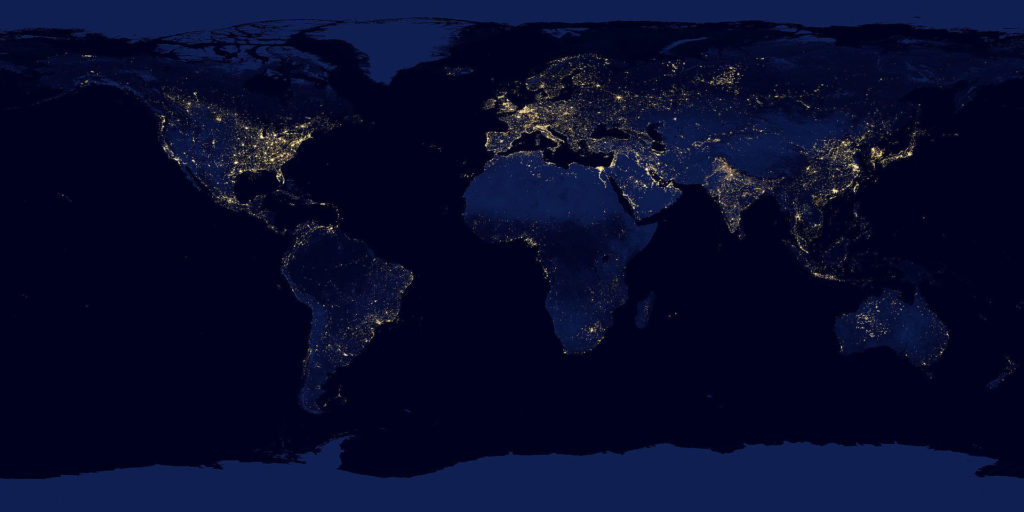

Penn State scientists have developed a technique that combines data on nighttime lights with public health data to help combat outbreaks of infectious diseases in the developing world.

Led by biology professors Nita Bharti and Matthew Ferrari, a team of researchers used satellite imagery, vaccination records and reports of measles cases to illustrate how fluctuations in population due to seasonal migrations could help improve vaccination coverage.

The researchers studied a 2003-2004 outbreak in Niamey, Niger that resulted in over 10,000 cases and nearly 400 deaths. Population estimates at the time did not take into account seasonal migrants, resulting in an underestimate of the population and an overestimation of the number of children vaccinated.

Using satellite images of nighttime lights, the Penn State team achieved retrospective estimates that much more closely matched actual, post-outbreak assessments of the vaccination campaign. The researchers also showed that their population estimates for two other cities in Niger could be used to coordinate vaccination and other public health campaigns when detailed vaccination records or disease case studies are not available.

“Access to vaccinations and other preventive health services is limited in much of the developing world,” explains Bharti, who recently studied the travel and health access patterns of people living in remote areas in northwest Namibia. “We’ve shown, however, that access to vaccines isn’t static through time. The same seasonal gatherings of people that we’ve previously shown to correlate with times of disease transmission risk could also be used to better target public health interventions — taking advantage of times of high population density to more efficiently distribute care.”

Or as Ferrari puts it, “Rather than looking at times of large gatherings — harvest season or cultural festivals — as high-risk periods, we can look at them as opportunities to serve people who are normally beyond the reach of conventional health systems.”

Bharti has done analogous projects using nighttime lights to map the impact of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti and to target populations for polio vaccination.

Rather than looking at times of large gatherings as high-risk periods, we can look at them as opportunities to serve people who are normally beyond the reach of conventional health systems.Matthew Ferrari

Unfortunately, the method is of limited use in situations such as the current migrant crisis in Europe.

“Many of the migrants in Europe are settling in areas that already have high nighttime illumination and thus the addition would not be very apparent,” he says.

Mobile phones might be a solution — a critical part of Bharti’s current work is looking at patterns of cellphone use and access.

“Cellphones have been used as an alternative method for detecting movement and human distribution,” explains Ferrari. “Part of this project is looking at how phones and satellite imagery can be used in tandem to understand movement and health system access in the lowest access populations.”

“Satellites are actually a pretty old technology compared to cellphones and social media,” adds Bharti. “But satellite-based measures are really appealing because we can look back in time and assess trends in patterns of human movement and distribution. Cellphones are an exciting new technology and have great potential for public health outreach, but the rapid rate of adoption means that we need to be careful about interpreting trends — the patterns might reveal changes in behavior or they might just reflect trends in accessibility to phones.”

The research was published last month in the journal Scientific Reports.