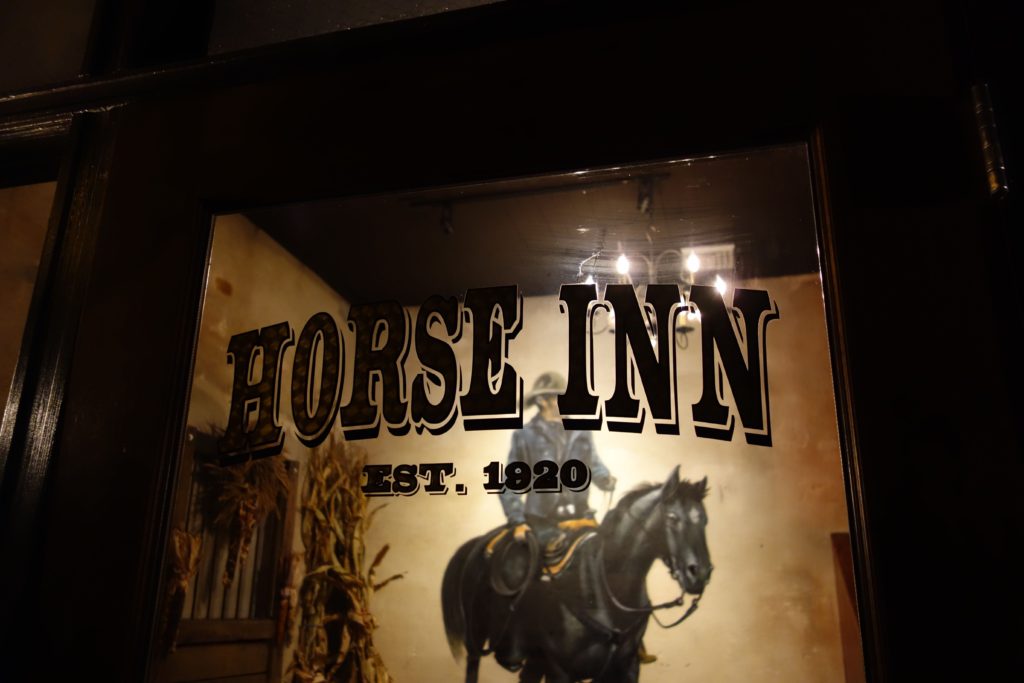

It’s Friday night and the Horse Inn is packed. There’s a wait for a table in the main dining room and the front bar is filled with pairs of diners and drinkers sipping on craft cocktails — perhaps a “Call to Arms” (Rittenhouse rye, Zaya rum, ruby port, boiled cider, pressed lime, Angostura) or a Doctor’s Orders (Market Alley gin, house tonic, basil, cardamom, grapefruit water) — and local craft beer.

It’s a scene that could be replicated in almost any major metropolitan area in the country: buzzing voices, plenty of dapper young urbanites, vintage jukebox, nostalgic bar games and low lighting.

But in other ways, you could be nowhere else but Lancaster City. The menu is rife with products from local farms. This is an eatery just as comfortable serving galumpkis (traditional stuffed cabbage) as it pairing pork shoulder with kimchi fried rice. If you watch long enough, you realize just how many folks seem to know each other. When a young couple gets engaged two tables over, the whole restaurant explodes in applause. The Horse Inn has actually been a drinking establishment since the 1920s, and while the new owners have spruced up the interior — horse stalls from its original use as a hayloft house booths — the space’s essential spirit remains untouched. It’s a classic Lancaster story: taking something old and good, and making it better.

That narrative is being replicated all across this Pennsylvania city. A new generation of locals, transplants and repatriates are transforming this compact burg, shifting the reputation of a metropolis that’s long been in its famous county’s bucolic shadow.

HOMECOMING

Ryan Martin, co-founder of Infantree, a local marketing and branding company, can trace his Lancaster heritage back 13 generations, but that didn’t stop him from moving away after college — first to Philadelphia, then to Harrisburg.

“Growing up in the county — Strasburg, which is southeast of the city — we didn’t have a whole lot of reasons to come downtown, except for Central Market on Saturday mornings,” he recalls. “My grandmother had a stand at Market for 60 years. She sold flowers. My grandfather was a grower. My parents were florists. That was the best part of Lancaster City for me, coming downtown to be part of that community on Saturdays.”

During those years away, Martin started to hear murmurings of a change happening in his native land. That tight-knit community he recalled from his youth felt like an opportunity. He moved back and eventually teamed up with Ryan Smoker, launching Infantree out of a fourth-floor loft above Prince Street Cafe. The popular coffee shop became both their landlord and their client. The company’s team has since grown from two to 12, serving the growing slate of local retail boutiques, breweries, distilleries, restaurants, city organizations and nonprofits.

“Over the last 15 or 20 years, but really in the last eight years, we’ve seen a real significant change downtown,” says Martin. “Galleries came in and started a little bit of a groundswell. We saw some refreshed boutiques coming in. The restaurant scene followed quickly on its heels. Businesses actually wanted to move from the suburbs to find locations downtown. With that came micro-industries: distilleries, breweries. All the clients that we serve. It’s been wild to be a part of that.”

Being a local also has its advantages.

“All of the work we’ve done from a branding and marketing perspective has been through word-of-mouth referral,” he continues. “We’ve built a business on this community. I’d say 60 to 70 percent of the work that we do is within a 30-mile radius of our downtown office.”

Businesses actually wanted to move from the suburbs to find locations downtown. With that came micro-industries: distilleries, breweries. All the clients that we serve. It’s been wild to be a part of that.Ryan Martin

Last year, Martin and Smoker actually became their our own clients, opening Ellicott & Co., a shop on Market Street selling American-made men’s clothing and accessories. The pair works with local makers — leatherworkers, metalworkers, textile workers — to stock their shelves.

The city is proving to be a fertile place for fledgling companies to find a toe-hold. Technology startups have a host of affordable office space and coworking options to choose from including the ever-expanding Candy Factory (profiled in our first feature on ‘The New Lancaster’) and PubForge. The latter, located above beloved bar and music venue Tellus360, is geared towards technologists: developers, programmers, designers.

One former tenant is Matthew Ranauro of BeneFix, a startup that simplifies the health insurance market for small businesses. He is another repatriate, having moved back to his hometown after stints in New York, San Francisco and Boulder, Colo.

“Being back here, it’s unbelievable,” says Ranauro. “The community is super tight. There’s definitely a lot more tech than when I grew up here. I can’t really ask for a better place, especially in this industry.”

Since last fall, BeneFix has quintupled their client list and, in doing so, outgrew Pubforge. But they didn’t go far, moving into a 2,400 square foot space on S. West End Avenue.

STREET LEVEL

Mayor Rick Gray has witnessed Lancaster City’s evolution firsthand: He’s lived in the same house on Prince Street — what he calls “the best $18,000 he ever spent” — for 44 years.

“During a lot of those years, you’d look outside at 11 p.m. and there was nobody on the street,” he recalls. “Now, if I go outside at 11 p.m. and look up and down Prince Street, there are people on both sides of the street walking. People have come back to the city. I think that’s true of a lot of our cities: I hear it from York, I hear it from Harrisburg, Bethlehem, Easton.”

The mayor credits two specific demographics with repopulating downtown: young people and baby boomers.

When it comes to millennials, “they want to be in the city,” he says. “I grew up with Leave it to Beaver, Father Knows Best — TV shows that represented suburbia as the promised land. My kids grew up with Sex and the City, Seinfeld, Friends. All urban settings. They want walkability. They don’t want car dependency. I can walk to 30 restaurants from my house.”

Meanwhile, many empty nesters are tired of mowing grass. They also want to ditch their cars, especially as they age. Downtown development reflects that demand: apartments and condos are being built that specifically target those 55 and older.

Gray, whose wife is an artist, also credits the vibrant arts scene with downtown’s resurgence.

“We have work by Lancaster artists hanging all over City Hall,” he says. “There have always been a lot of artists here because of the affordability and easy access to the major markets. In the last 10 to 15 years, [we went] from a wholesale market to a retail market. I know locals now that can make a living being an artist, which is a difficult thing to do.”

That creative energy translates to craftspeople as well. RudeWood Design‘s Jeremiah Linton grew up in South Jersey. He met his business partner Alex Rudegeair at Thaddeus Stevens College of Technology in Lancaster where they both studied carpentry. These days, the duo does custom woodwork with a focus on commercial restaurant and bar furniture.

After graduation, Linton spent two years in Philadelphia, but Lancaster drew him back.

“I moved [to Philadelphia], and was networking and working with different people,” he recalls. “When I moved away, I was like, ‘I didn’t make any lasting connections.’ But in the two years I’ve been here, I’ve made a lot of friends, built a lot of relationships. I think the business community in Lancaster is really into helping each other out. When one of us is successful, we can give back to the others in some kind of way.”

Rudewood is based out of an old printing facility, and they’ve created an impromptu collective, renting extra space to other artisans. Most of the company’s work is local. Very local.

“All of the jobs we’ve done in Lancaster City, we’ll walk there,” he says. “I think we’ve benefited a lot from coming here instead of staying in Philly.”

CITY LIVING

From old manufacturing facilities to heritage homes, there are all sorts of unique spaces on offer in Lancaster City. The built environment — well-lit sidewalks, historic buildings, industrial relics, charming brick rowhomes — can surprise visitors familiar with a Lancaster County brand based on buggies and dairy cows. Notably, the city boasts dozens of old tobacco warehouses that have survived and been converted into work and living spaces.

One of those loft-livers is Deborah Barber. An employee at Nimblist (formerly Performance Environment Design Group), Barber moved to the Harrisburg area after college, where she met her husband. Twenty years ago, they moved to Lancaster County and then, seven years after that, into the city.

“It was the best thing we’ve ever done,” she recalls. “We really wanted [a living space] that would fit into our creative aesthetic as a couple and was more unconventional. We had looked and looked for a warehouse space and found the space that we have now. It has such a creative soul and energy to it. I knew the minute we walked through that building, it was where we were meant to be.”

Until last year, Barber’s work was still in the capital, but she wanted a job closer to home. Nimblist is a perfect example of the kind of mid-sized, creative-economy company that thrives here. The seeds for the enterprise were sown almost 20 years ago by Spike Brandt — who’s local to Lancaster — and L.A.-based Justin Collie. They met as roadies and came up through the lighting and design world. The business, which creates environments for live events, has since grown to about 20 employees. Clients include the NFL, musical acts, the Robin Hood Foundation and the SyFy network. The company is part of a booming event production industry centered around Lancaster City and nearby Rock Lititz.

As Nimblist grows, the staff is evolving.

“When I came in, pretty much everyone was local,” recalls Barber. “Since I’ve been here, we’ve hired and relocated two people from out of state. We have a third person slated to start with us [last] December who is moving from another country. We have a fourth person who we hired as a result of her partner being relocated to TAIT [in Lititz].”

Barber thinks there are still things Lancaster City could do to ease the way for those transplants.

It has such a creative soul and energy to it. I knew the minute we walked through that building, it was where we were meant to be.Deborah Barber

“One thing I’ve noticed and heard from our staff is that we don’t seem to have many realtors who handle the rental market,” she explains. “We’re looking for highly-skilled programmers and lighting designers — it’s a competitive market. It’s not easy to find those people, and when you do find them, I need to be able to tell them there are some cool places for them to live and a range of cool places for them to go out and eat.”

Part of that mission includes dispelling preconceived notions. Fortunately, often all it takes is a visit.

“We rent out one of our rooms on Airbnb,” says Barber. “The people we’ve had stay all say, ‘We had no idea that Lancaster would be like this’ or that ‘you have so many cool places,’ or that ‘living spaces like what you have exist.’ If you want that funky warehouse, there are those spaces. There are condos. There are single-family homes that are gorgeous and historic. And there are really quaint rowhomes that people have taken and redone.”

DINING OUT

If all it takes is exposure to fall in love with Lancaster City, then Susan Louie and her husband Rafael Perez are Exhibit A. Before opening their charming French BYOB Citronnelle, the longtime New York City residents experienced the city via friends who moved south.

“We started visiting them and fell in love with the place,” recalls Louie. “We bought a [weekend] house, but weren’t fully committed yet. We were both still working in New York. Then we saw this building — which was an abandoned print shop — and thought, how about changing our lifestyle?”

They purchased the property on Orange Street in 2009, moved to Lancaster City permanently in 2012 and opened Citronnelle in 2013. The couple were not experienced restauranteurs: Louie was fashion designer and her husband a chef. They had to learn the business from scratch, and figure out what exactly people wanted to eat in this part of Pennsylvania. The team buys everything locally, mostly from nearby Central Market. Seasonal ingredients go into dishes like grass-fed, pasture-raised New York strip with a mushroom-and-potato roulade or their signature creamy crab croquettes, served on a bed of cucumber salad and topped with yuzu wasabi aioli.

“We don’t have shoo-fly pie here,” explains Louie with a laugh. “We don’t have buttered noodles…We see a lot of people who come in here a little trepidatious. They read an ingredient on the menu and aren’t sure what it is. But we’re so happy to explain it to them. We’re not an uptight restaurant. We’re not hoity-toity — we just want to feed people. And if they learn a little something about what they’re eating, it’s great.”

Fortunately, a growing number of eateries are catering to the city’s changing palette, whether it’s students looking for fast-casual poke at Chop Sushi or couples nibbling on Neapolitan pizzas at the perennially packed Luca. The restaurant community knows that the city’s growing reputation as a foodie haven benefits them all.

Fortunately, a growing number of eateries are catering to the city’s changing palette, whether it’s students looking for fast-casual poke at Chop Sushi or couples nibbling on Neapolitan pizzas at the perennially packed Luca. The restaurant community knows that the city’s growing reputation as a foodie haven benefits them all.

“In New York, there are so many restaurants that you can’t really get to know anybody; they come and go so fast,” says Louie. “We’ve made friends with so many other restauranteurs. They’re so supportive of us, especially because we’re so little and just starting out. There’s a really nice sense of community here.”

Daniel Falcon is another local restauranteur. He came to the area from Puerto Rico 38 years ago when he was two. It is hard to tell the story of Lancaster City’s resurgence without talking about the Latino population which makes up almost 40 percent of the municipality’s 60,000 residents. They are an essential part of the small business community, whether that’s running neighborhood groceries or contributing to the diversity of downtown offerings.

We’re not an uptight restaurant. We’re not hoity-toity — we just want to feed people. And if they learn a little something about what they’re eating, it’s great.Susan Louie

Falcon was always trying to find a way to work from himself, growing a mall kiosk business into four clothing stores before changing course and getting into two of the city’s booming industries: real estate and night life. In September 2014, he opened Lancaster Cigar Bar on King Street. He has since bought up more property in the same building, launching Old San Juan Latin Cuisine and Rum Bar, and is hard at work on another concept across the hall: a neighborhood pub with a Prohibition-era vibe.

“Lancaster has a solid economy, and one way to attract young professionals to your city or town is to give them something to do when they’re done working,” he explains. “I think Lancaster is doing a good job at providing night life. I think we can do better, and we’re on our way there. I think the local government has been pretty supportive of that whole idea.”

While the city’s growing population is obviously great for Falcon’s bars and restaurants, it has also impacted his real estate investments.

“There seems to be more a demand for people wanting to live in the city,” he says. “People are actually selling their homes in the suburbs and moving into the city. Once that started happening, the demand for higher-end rental properties went up. Investors are meeting those demands. I’m in the rental business, so that’s what I’m doing with my units. I’m fixing them up and making them a little nicer, collecting more rent as well.”

Nicole Vasquez is another young Puerto Rican entrepreneur. She grew up in Lancaster City, spending most of her childhood on West King Street. From a young age, she loved fashion and dreamed of opening her own clothing boutique. Flash forward to 2012, when she launched That Shuu Girl at the tender age of 25.

I have found an absolute love for the community here. If you do right by them, they take really good care of you.Ryan Martin

“Something I love about downtown Lancaster City is you don’t see any franchises,” she says. “When you go into a small business, you’re pretty much meeting the owner and you feel welcome, you feel comfortable.”

Vasquez credits local groups like the Lancaster City Alliance and ASSETS’ Women’s Business Center with helping her figure out how to run her business and connect with local designers.

That reliance on community — both in terms of organized resources and likeminded peers — was something repeated again and again by residents and business owners.

“I have found an absolute love for the community here,” says Martin from Infantree. “If you do right by them, they take really good care of you. We’ve been able to survive because of the whole ‘buy local’ thing. Lancaster has a whole different appreciation for it: People here want to support anything that is authentically Lancaster.”

LEE STABERT is editor-in-chief of Keystone Edge. Tell her your favorite things about Lancaster @stabert.

This is the second installment in a series of stories Keystone Edge will be publishing on the evolving identity of Lancaster (read the first feature here). This content was created in partnership with the Economic Development Company of Lancaster County and partner organizations.

All images by Lee Stabert