Before Philadelphia native Christian Cantiello founded Keystone Sign & Company, he was an art-school graduate paying the bills as a bartender, but he never stopped indulging his creative side.

“While I was in the bars, I ended up doing lots of signs, like chalkboards and markers and stuff like that,” he says. “That kind of piqued my interest in the whole sign-painting thing.”

Sign-painting is an art that goes back centuries, but once vinyl printouts became the norm, the practice of hand-painting signs dwindled to relatively few practitioners by the 1970s and ’80s.

Born and raised in South Philly, Cantiello was “always interested in art and graffiti and letters.” He eventually bought a supply of paints and brushes, and built on his existing skills, learning all he could from YouTube and books. Then the owners of Nelson’s Ice Cream, a family-owned creamery in Royersford (about 10 minutes north of Phoenixville), reached out. They hired Cantiello to do the windows at their new shop.

Born and raised in South Philly, Cantiello was “always interested in art and graffiti and letters.” He eventually bought a supply of paints and brushes, and built on his existing skills, learning all he could from YouTube and books. Then the owners of Nelson’s Ice Cream, a family-owned creamery in Royersford (about 10 minutes north of Phoenixville), reached out. They hired Cantiello to do the windows at their new shop.

Cantiello took a week off from pouring drinks to complete the job, intending to return when it was done. But after that gig, others kept coming in. He never went back to bartending.

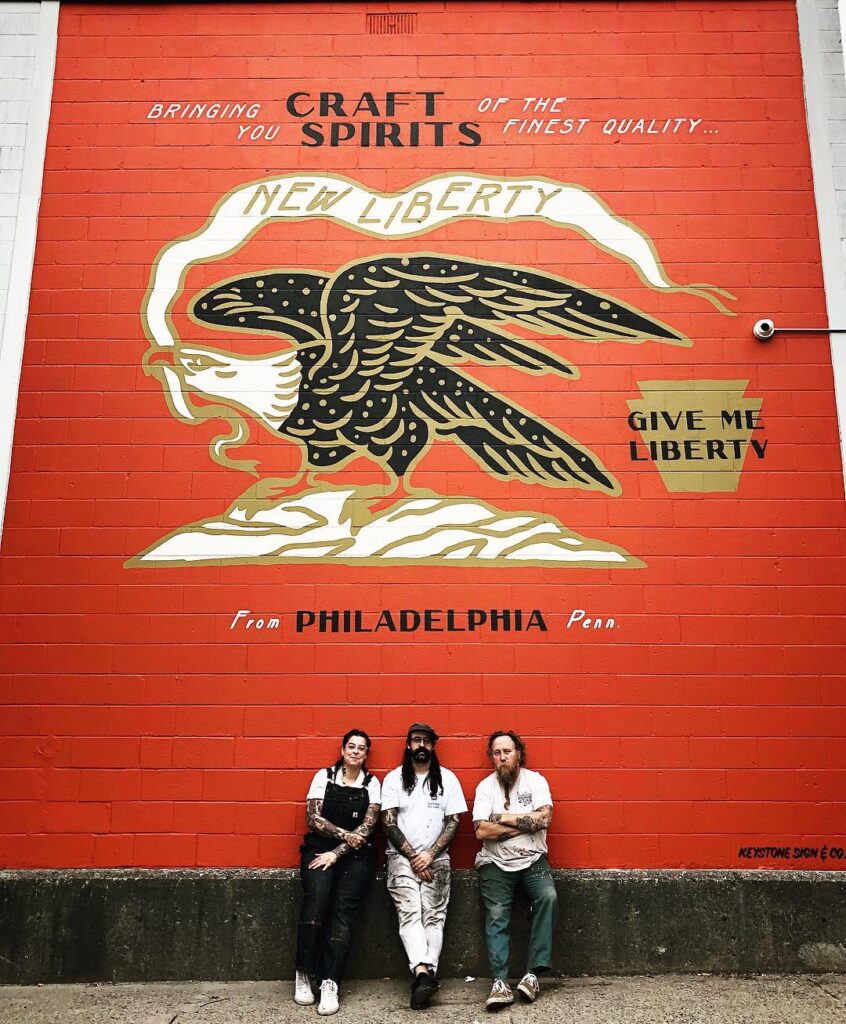

According to Cantiello, Sign Painters, a 2012 book about the field — which was followed by a popular film of the same name the following year — helped spark a resurgence in the art form, inspiring him to officially launch Keystone Sign & Company in 2014.

While the business was still young, he became interested in glass gilding, an art that goes back centuries but has its current roots in 18th-century France. These artists work on the reverse side of painted glass, brushing on a clear, watery gelatin mixture and then applying small, delicate sheets of gold leaf thinner than paper. As the gelatin dries, the gold bonds to the glass with a mirror finish and is sealed from behind with a coat of paint, so that it shines through in front.

Cantiello wanted to meet veteran Philly sign-painter and glass gilder Gibbs Connors, and was able to reach out through mutual friends. It turned out Connors’s shop was a five-minute walk from his house.

“He said to pop by anytime,” recalls Cantiello.

Their relationship started slowly, with Connors wary of sharing skills that might cost him customers. But after Cantiello taught himself the art of glass gilding, the two began working together regularly. For the last five years, the two independent painters have often hired each other to help with jobs.

If you’re a sign-painter and don’t have design skills, you’re not going to go very far.Christian Cantiello

But other than that, Cantiello is still running a one-man operation, not just painting signs, but often designing them, too. Traditionally — before everything was designed with the help of computers — sign-painters had to be skilled at drawing and lettering.

“They would come up with layouts and designs that were better than anything a graphic designer could come up with,” argues Cantiello. “If you’re a sign-painter and don’t have design skills, you’re not going to go very far.”

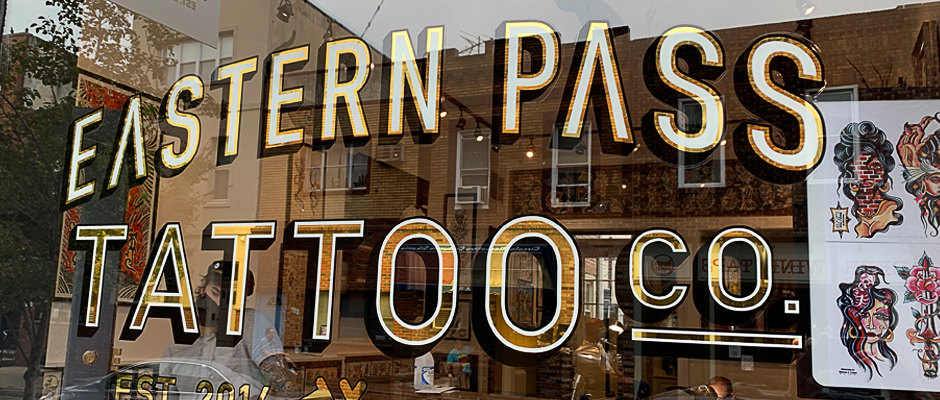

Some customers reach out with a design already in hand, some ask him to come up with one, and some collaborate with him. He’s particularly proud of a job for Eastern Pass Tattoo — the business recently moved from an upstairs space on South Philly’s East Passyunk Avenue to the downstairs storefront, which boasts large windows.

Owner Scott Bakoss wanted an eye-catching gold leaf display. Cantiello sketched out an initial design and worked with Bakoss to finalize the look, ultimately completing a large window, a new door sign, and the address on the transom in gold leaf with black and white paint.

“Every time you drive by, it kind of turns your head,” he says of the finished job.

Operating his own sign business for the last several years, as many small businesses are looking to get that customized, one-of-a-kind look for their shops, has confirmed Cantiello’s belief that nothing replaces work done by hand. Tiny imperfections just add to the charm.

“I can look at signs and alphabets … and I can know who did it,” he says. “Whereas online, it’s just so rigid … it doesn’t compare to the feeling of something truly made by hand.”

ALAINA JOHNS is a Philadelphia-based freelance writer and the Editor-in-Chief of BroadStreetReview.com, Philly’s hub for arts, culture and commentary.