This story was produced by the PA Wilds Center for Entrepreneurship and originally appeared on pawilds.com.

Cruising along Route 6 just west of Port Allegany in the Pennsylvania Wilds, it’s hard to miss the sprawling stone structure built into the mountainside.

There is an air of mystery about this property in the Seneca Highlands. Many PA Wilds tourists pull off the road to take a closer look.

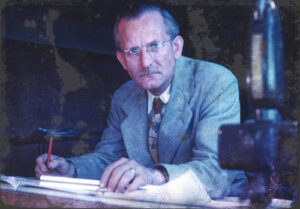

Turns out this eye-catching structure is Lynn Hall, built by Port Allegany builder and designer Walter J. Hall (1878-1952). At first glance, it recalls Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959), with especially strong visual ties to the world-famous architect’s Fallingwater in southwestern PA. Built out over a waterfall, that iconic structure was named the “best all-time work of American architecture” in an American Institute of Architects poll.

Well, turns out Fallingwater has Walter J. Hall’s touch all over it — he partnered with Wright on the iconic home, serving as the chief contractor/builder.

Across the Pennsylvania Wilds, generations of Walter Hall’s family were known for their skills in the building trades. Walter’s grandfather, Paul Hall, founded a company back in the 1800s. John Hall (Walter’s father) owned and operated one of the first sawmills in Port Allegany; Walter’s brother Howard later took it over.

As self-taught designers and building contractors, Walter and Howard specialized in masonry construction using local stone, building more than three-dozen homes in the Port Allegany and Smethport areas.

CREATING LYNN HALL

Like Fallingwater, Port Allegany’s Lynn Hall is an example of Organic Modernist architecture. Walter was an early adopter of this aesthetic, which allows the natural surroundings to determine the look of a structure.

Walter dreamed big. His Lynn Hall concept was a combination ‘country roadside inn’ and family home. It would include hotel rooms, a restaurant, dance hall, guest house, gas station, and an office for himself and his architect son, Raymond Viner Hall (1908-1981).

A highly prolific architect, Raymond designed Renovo High School, Port Allegany’s Elementary and Union High Schools, Keystone High School in Knox, Austin Elementary and Roulette Elementary Schools in Potter County, the Moose Lodge and fire station in Port Allegany, along with dozens of homes and other structures across the Pennsylvania Wilds. A talented father-son team, Raymond designed and Walter built.

Letters in the Fallingwater archives show Walter and Raymond were admirers of Frank Lloyd Wright’s style. At one point, Raymond wrote to Wright inquiring about studying at Taliesin, Wright’s home, studio, school, and 800-acre estate in southwestern Wisconsin.

THE FALLINGWATER CONNECTION

With Lynn Hall construction underway, along came Edgar Kaufmann Sr. (1885-1955) and Frank Lloyd Wright.

In 1935, Kaufmann, a department store tycoon known as the “Merchant Prince of Pittsburgh,” commissioned Wright to design a family retreat on his property along Bear Run in the Laurel Highlands, an hour and a half drive from the city. Kaufmann had his architect, but he had fired the original contractor and was now in dire need. Walter J. Hall got a call from Pittsburgh that would change his life.

In that Raymond Viner Hall letter to Wright, he told the famous architect that his father, Walter, was “a master builder in the real sense of the word.”

That correspondence prompted Wright to send his son, John Lloyd Wright, to Port Allegany in 1935 to meet with Walter. After seeing Lynn Hall, John reported to his father that Walter was a “stunning stone builder.” Wright and Kaufmann made an offer. Walter accepted.

In May 1936, Walter dropped what he was doing at Lynn Hall and headed to Bear Run to serve as Fallingwater’s builder at a salary of $50 a week, the equivalent of $900 in today’s money.

TWO ‘CREATIVE GODS’ COLLIDE

Verbal sparring between architect and builder is common during the construction process. Hall and Wright were no exception. Though their design philosophies were similar, they butted heads. Sometimes it got downright personal. Wright would show up at the Fallingwater construction site in a cape and his signature pork-pie hat. Walter would mimic him, wrapping himself in an old blanket and putting a kerchief on his head.

When Wright was commissioned to design the S.C. Johnson headquarters in Racine, Wisconsin, he had less time for the day-to-day construction at Fallingwater. Walter’s presence became even more crucial for its completion.

Walter’s penchant for “artistic license” and making changes “on the fly” in Wright’s absence drove the architect mad. He fired off an angry letter to his contractor:

“It is only fair to say to you directly that you will either fish or cut bait, or I will. I am willing to quit if I must but unwilling to go with my eyes open into the failure of my work. I have not built one hundred and ninety of the world’s important buildings without knowing the look of the thing when it turns up on the job. Failure, I mean, by way of treacherous interference.”

Wright demanded Kaufmann fire Walter immediately. Kaufmann refused.

Walter would see Fallingwater to completion. When it was finished, its unique design captivated the world. Frank Lloyd Wright and Fallingwater graced the cover of TIME Magazine in 1937.

Eventually, Wright offered Walter a job as his chief builder/contractor. Walter declined and headed back to Lynn Hall. He had unfinished business.

From Fallingwater to Port Allegany

Walter took great delight in watching Lynn Hall become a favorite venue for well-dressed guests from as far away as Cleveland, Buffalo and Pittsburgh. They enjoyed dining in the glow of the huge fireplace near a beautiful stone staircase leading up to the grand ballroom, overlooking the beautiful Allegheny River Valley.

As America fell in love with the automobile, Walter added a gas station. Scores of tourists traveling Route 6, the “Transcontinental Roosevelt Highway,” stopped in to fill up and grab a bite to eat.

Unexpected events eventually took a toll on the business. Lynn Hall managed to survive the Great Depression, but the 1940s brought World War II and gasoline rationing. Traffic along Route 6 slowed to a trickle.

According to Walter’s great-grandson Doug Hall, it did not help business that Walter was a teetotaler.

“Great Grandpa Walter refused to get a liquor license,” he explains. “But he would always look the other way when customers brought their own for parties upstairs.”

Doug lived at Lynn Hall with his father, Raymond Morton Hall.

“I was too young to know Lynn Hall as a working gas station and restaurant, I knew it as architecture’s offices,” he says. “We lived in the adjacent cottage house from the time I was nine until I was 16.”

It was a fun place for a growing boy.

“I remember playing for hours and hours in the huge stone quarry up in back of Lynn Hall,” says Doug. “It was a magical place to live! I remember Christmases with those Shiny Bright Christmas tree ornaments, four fireplaces — one in the party room downstairs burned logs four feet long. I remember watching the waterfall cascading over the flagstone in the indoor trout pond. It was strange because I grew up thinking it was ‘normal’ to be hosting parties nearly seven days a week.”

Doug said there was always this perception in town that the Hall family was extremely wealthy.

“Truth was, we were not so much ‘rich’ as we were industrious,” he says.

LYNN HALL’S FALL

Walter J. Hall died in 1952. By 1954, the restaurant and gas station closed. Walter’s son Raymond Viner Hall kept Lynn Hall occupied with his architecture offices. After he died in 1981, the decline of Lynn Hall began. It accelerated after Ray’s second wife inherited rights to the place. She moved out in 1990 and, for the first time in more than 50 years, the place sat vacant.

“It was a bad time,” says Doug. “There was so much family dissension. She refused to spend money to fix the roof. It got really bad and the structure began to deteriorate. I broke down and cried at the shape of the place when I visited a few years later.”

The slow, sad decline of Lynn Hall continued as tall pines encroached on the building, obstructing the beautiful view of the valley. It appeared Mother Nature was reclaiming the mountainside.

REIMAGINING LYNN HALL

Lynn Hall sat vacant for nearly 25 years. Gary and Susan DeVore came to the rescue in 2013.

The new owners share a love of historic structures.

“Once we realized the history and significance of Lynn Hall, we knew we had a chance to preserve an important piece of architectural history and, in the end, helped write some history ourselves,” says Gary.

Gary, whose father was a stone mason, knew a lot about architectural history.

“I spent four years in the architecture program at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and toured Frank Lloyd Wright’s school of architecture at Taliesin many times and studied his organic structures,” he explains. “I took one look at Lynn Hall’s stonework and knew it was either a serious Wright influenced design, or actually associated with him. Turns out, I was right on both counts!”

At the time, Lynn Hall was a disaster. The remnants of 1972’s Hurricane Agnes unleashed a torrent of water through the building’s rear wall, leading to rot and mildew inside.

“We had no idea of the massive challenge we had taken upon ourselves,” recalls Gary. “If looks could have killed, my wife would have caused my death many times over as we worked on Lynn Hall.”

An accumulation of pine needles and pine cones twelve-inches deep had pitted the roof and it leaked like a sieve in places.

“The leaks led to massive ice structures encasing the electrical panel,” says Gary. “Nobody knew if the electric, heat, water or sewage systems worked – and they didn’t. Opening each wall and ceiling was a ‘wonder what we will find next’ moment.”

Next came the task of getting rid of the tall trees.

“It involved taking down 70 pine trees, sixty to one hundred feet tall, thirty inches in diameter and all of them had to be felled in a narrow space of only twenty-five feet between the building and Route 6,” he explains. “It took finding Shaun Nance, a local arborist and tree cutter, who climbed each one, trimmed branches, felling them in sections, never once touching either the building or the highway.”

THE RESCUE MISSION

Local artist Stephanie Distler, engagement specialist at the Wilds Cooperative of Pennsylvania, visited Lynn Hall in 2013 around the time the DeVores took over. She got a big surprise when she returned in autumn 2016 for a Wilds Cooperative juried art show.

Entering the building to help set up, Stephanie couldn’t believe what the new owners had accomplished in a few short years.

“Noticeable was restoration of landscaping, the clean appearance of the exterior stonework, the work done on the pumphouse/cottage to serve as living quarters, and the organization of Walter and Raymond Viner Hall’s papers,” she recalls. “Rooms were partially staged, utilities were on, there was usability of the bathrooms, the fireplaces, the beautiful [midcentury modern] style wooden chairs, and so on.”

After several years of labor, the DeVores felt they had taken their rescue mission as far they could. At that point, the couple had a decision to make: If they sold, how could they prevent Lynn Hall from once again falling into disrepair?

“We were afraid someone would buy it, fail as a business and let it go to ruin again,” recalls Gary. “We also knew that the next step was going to take even deeper investments than we could handle. We sent letters out to all our architectural and historical contacts for ideas, but nothing solid [came about].”

They began looking for someone to take over Lynn Hall.

The DeVores knew of the historic homes site CIRCA and realized there were almost no midcentury modern homes in their listings. They decided that it would be the best place to advertise, not only nationwide, but worldwide.

Rick Sparkes and Adam Grant of South Florida answered the ad.

“We listened to their story, their talents, their financial ability and their personalities,” says Gary. “We did not hesitate to say, ‘SOLD!'”

A NEW ERA BEGINS

New owners Adam Grant and Rick Sparkes have extensive design backgrounds, and the successful restoration of two historic homes in Fort Lauderdale under their belts.

Grant recalls their first Lynn Hall visit: “Upon arrival, the building was still in such bad shape that our immediate reaction was one of horror. It took all our courage to resist the ‘flee’ instinct. However, when we entered the front hall and viewed the multi-level stonework, the grand fireplace in the old restaurant space and the interior fountain two levels up, we were sold. It took us about an hour of walking around before we had a full vision of what the building could be and we finally made an offer.”

“Credit the DeVore’s for keeping the place from the wrecking ball and putting the ambitious rescue work on track,” he adds. “We owe them a huge debt of gratitude for their part in saving this historic landmark, especially for reawakening interest in this property that most people gave up on long ago.”

Picking up where the DeVores left off, Grant and Sparkes spent time and money — a LOT of money — on supplies and labor to return the grand old place to a livable condition.

There was a point where the restoration effort was overwhelming.

“Basically, the place was nearly uninhabitable,” he recalls. “We ended up taking on pretty much all the work ourselves including stonework, electrical, plumbing, woodwork, roofing, windows, and so on.”

“Many people have a predisposed impression of what a building like this is like to live in — damp, dark, dirty,” he adds. “This is clearly based on the decades Lynn Hall sat vacant as it began to fall back into the hillside…When we discuss the tenets of this type of architecture and the emotion it elicits — with compressed ceilings, fluid levels and windows used to blur the interior/exterior exchange — visitors have a new appreciation for all we have done.”

So, has the restoration mission been accomplished in full?

“We are always hesitant to answer that question as a building like this is never complete,” explains Grant. “I would say we are two-thirds completed. All the major infrastructure is done except for a section of roof over the family apartment area.”

He is also quick to point out that the eight-inch-thick poured concrete roofs that cantilever out of the hillside have been resurfaced and made into “living roofs” with planters.

And the place (still) never fails to attract attention: Motorists still hit their brakes and pull off the highway to take a closer look.

THE HALL FAMILY LEGACY

With few family members left, Doug Hall — who used to play in that big flagstone quarry out behind Lynn Hall, who mowed the lawn and washed the windows, who decorated the Lynn Hall Christmas Tree with those vintage Shiny Bright ornaments — considers himself fortunate to have called Lynn Hall home in his lifetime.

“I really did not know how lucky I was at the time,” he says. “Looking back at what my ancestors did, it just blows me away.”

In some circles, a debate continues: Which came first, Lynn Hall or Fallingwater?

Did Walter “borrow” the idea for Lynn Hall? What impact did Lynn Hall have on Fallingwater?

Clearly, documents show that Walter’s ideas were influenced by Wright, and that he had traveled to Buffalo to study Wright’s design of the Darwin Martin House and other “Wrightian” creations. However, Walter and son Raymond Viner Hall were not merely Frank Lloyd Wright imitators, they pushed to further their own design ideals.

Wright conceived Fallingwater’s design in July 1935, finished it in September, and presented it to Edgar Kaufmann in October of that year. Fallingwater construction got underway in June 1936 and was completed in 1937. Walter had broken ground for Lynn Hall back in 1934.

According to the Cornell University School of Architecture, some of Fallingwater’s flagstone came from the stone quarry behind Lynn Hall, with Walter’s brother Howard delivering a truckload or two to Fallingwater.

There is no mystery that Walter Hall played a huge part in the creation of Fallingwater, and was the prime executor and maestro of Fallingwater’s masonry style.

Lynn Hall was officially entered into the National Register of Historic Places in 2007 with the following notation in the Historical Places Designation document:

“Lynn Hall is an expression of understanding of ‘Wrightian’ design principles, making it significant on its own, resulting in a lasting architectural legacy. Lynn Hall retains integrity as an important example of Pennsylvania modernistic architecture.”

To view progress of Lynn Hall and find tour information, please visit the website: lynnhallpa.com