Infrastructure and inequality have become bywords in contemporary American politics. And according to Penn State Associate Professor Peter Aeschbacher, this important national movement got an early start in Pennsylvania.

He argues that the impetus for community design centers — like the three in the Commonwealth — has roots in a fiery keynote address from civil rights activist and National Urban League head Whitney Young at the 1968 national convention of the American Institute of Architects (AIA).

Young pointed to public housing developments he termed “vertical slums,” lacking adequate bathrooms, with no play space for the thousands of resident children. How could self-respecting architects design buildings so out of touch with human needs?

“You are most distinguished by your thunderous silence and your complete irrelevance,” he said to the American architects of the late ’60s.

“They heard this and thought, oh my goodness, he’s right, we should actually be doing something,” explains Aeschbacher.

This awareness dovetailed with the rise of the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), which became a cabinet-level agency in the late 1960s. That meant a centralization of federal dollars for local design projects. This year, the nationwide Association for Community Design will celebrate its 40th anniversary.

Design centers now dot the U.S. map, and we have three: Philadelphia’s Community Design Collaborative, Penn State’s Hamer Center for Community Design in State College and Design Center Pittsburgh.

So what do these institutions do?

We help communities at the intersection of architecture and community development, which is really helping communities learn how to deal with their built space.Chris Koch, CEO of Design Center Pittsburgh

“The Collaborative provides pro bono preliminary design services for nonprofit organizations that are doing some kind of development work,” explains Heidi Segall Levy, The Collaborative’s design services director.

The organization targets “a gap in funding” trapping nonprofits that need facility upgrades. Before they’ll fund improvements, donors want to see plans and cost estimates — but that costs money. It may be invisible by the time you get to the ribbon-cutting, but according to Levy, “pre-development” makes up the first 15 percent of the process. The Collaborative helps match these nonprofits with individuals and firms who can be of service.

The mission is similar in Pittsburgh.

“We help communities at the intersection of architecture and community development, which is really helping communities learn how to deal with their built space,” says Chris Koch, CEO of Design Center Pittsburgh. Using a mix of volunteer individuals and firms, and public agencies, the Center executes planning and urban design projects and grants in the Pittsburgh area. “We still have a lot of communities that are trying to rebound from the disinvestment that happened in the ’70s and ’80s.”

Pennsylvania’s design centers are good examples of two of the main types nationwide. Some — like those in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia — are stand-alone nonprofits.

The Hamer Center falls into another category: university-based community design centers. Founded in 1999, its work and mission are continually evolving. According to Aeschbacher, these higher ed-supported centers “are always creatures of their curriculum,” and they invest student and faculty skills in studies on community development, the built environment, natural resources and conservation.

Aeschbacher came to Penn State from Los Angeles to helm Hamer from 2004 to 2009, and now guides work there as an associate professor with joint appointments in architecture and landscape architecture.

He believes that Pennsylvania helped launch the community design center movement even before the rise of HUD and Young’s call to action.

“The earliest mention of a design center was in Philadelphia” in the early 1960s, under Karl Linn, an architecture professor at the University of Pennsylvania, he explains. Working with the city’s Department of Licenses and Inspections, it targeted vacant lots in North Philadelphia for makeovers, creating parks, gardens and plazas. This model spread, leading to similar efforts in Baltimore and Washington, D.C. Starting around 1967, Augustus Baxter, an African-American champion of the settlement house movement, launched a Philly-based nonprofit design and planning collective called The Architects’ Workshop, which, like HUD and design centers today, “were trying to mix sociology with design on the ground.”

The work of the modern design centers ranges widely.

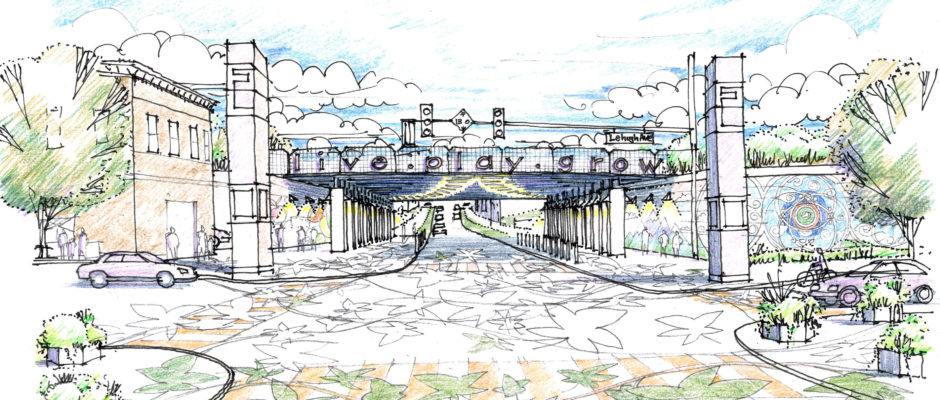

In 2016, the Collaborative wrapped up the latest iteration of its Infill Philadelphia program, running since 2006. These projects have targeted affordable housing, commercial corridors, industrial sites, food access and stormwater management. The latest round, an 18-month international design contest dubbed Play Space, provided a total of $30,000 in prize money for volunteer design firms. They produced exciting plans for three sites badly in need of upgrades: a recreation center, a school and a library.

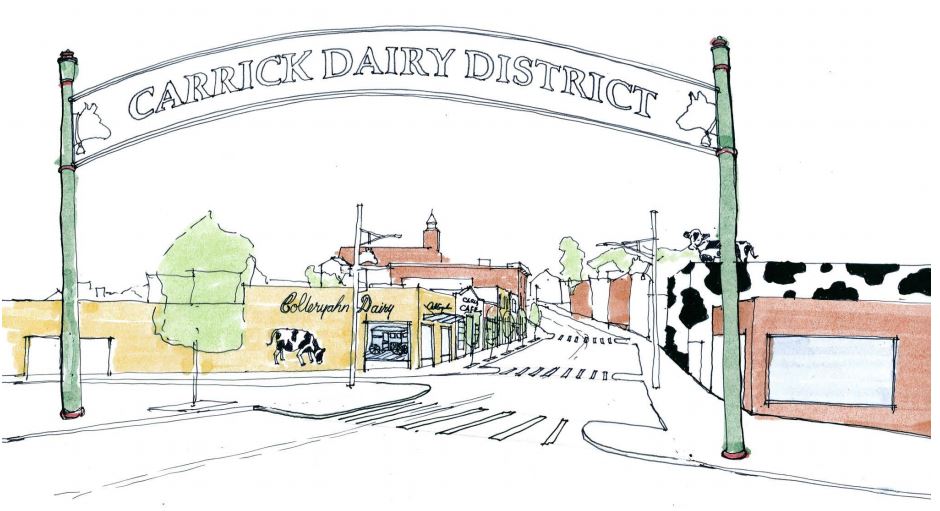

In Pittsburgh, the project that stands out to Koch is 2015’s Centre Avenue Corridor Redevelopment and Design Plan in the Hill District, a major vision for an iconic commercial and residential corridor.

The Great Migration transformed the Hill District — historically an immigrant community — into a vibrant center of African-African life (it was the birthplace of playwright August Wilson and a fount for jazz), but massive displacement and redevelopment in the 1950s led to rampant poverty and disintegration of the corridor. Things may be changing though, especially with a new hockey arena in the lower Hill District.

“How do we make sure that development of the neighborhood is synergistic with what’s happening in our commercial district?” says Koch. “We really have to talk about what does it mean to want to become and remain an African-American community that has a strong business district? How does identity become part of the built space?”

The Centre Avenue plan was administered via the Design Center’s Design Fund Program.

In 2014, a standout Hamer Center project produced Marcellus by Design, a study on the impacts of natural gas drilling in north-central Pennsylvania’s Tioga County. In lieu of urban visioning and specific development projects, the Hamer Center digs deep into questions of how we coexist with the modern natural landscape. Projects like Marcellus by Design wrestle with social, environmental and economic questions, spanning energy, food and historic sites. With in-depth looks at the lives and needs of residents and workers, the project developed locals’ capacity to understand and explore the ongoing design, safety and preservation issues of Pennsylvania’s booming natural gas industry.

Each Pennsylvania design center leader has a take on what “infrastructure” means today, and how we can better understand and develop it.

Part of the trouble is that “people think of [infrastructure] like a basic need that can’t be exciting,” says Levy. But when you mix in community-engaged design, it’s another story, as with Philly’s revamped South Street Bridge. “It could’ve been rebuilt just replacing it the way it was,” but involving the community in the design process highlighted the need for a multi-modal pathway and new lighting.

Koch would call that a good example of modern, community-integrated design.

“We want to talk about, how does a 21st century community look?” she says. “Not rebuilding what was here in the ’50s and ’60s, but building on that history and figuring out what is really next for us as a city as we start to fill back up again.”

Good infrastructure is also about time, argues Levy: not waiting until “that emergency moment when you have to address it quickly,” as well as time “to include community, to go through a design process” that allows everyone to truly understand how that infrastructure will be used.

For Koch, it’s also about building the capacity of communities to evaluate designers and developers for themselves, and making sure community voices come before dollars in any development timeline: “Once money’s on the table, that dialogue becomes so much more difficult,” she says, versus creating a “common vision” in the pre-design process.

We want to talk about, how does a 21st century community look?Chris Koch, CEO of Design Center Pittsburgh

Aeschbacher adds that we need a bigger lens on development in general. One example is the perennial controversy of “affordable housing” — whether it’s dubbed public housing or workforce housing — for those dubious about “the worthiness of the poor to receive aid.”

Instead of debating individual projects, we need to “think about affordable housing again as one piece of the larger built environment puzzle,” he explains. “It’s not the artifact itself that doesn’t work, it’s the larger system in which it sits.”

That system includes jobs, public spaces and equitable access to parks, which in turn are tied to health and social capital.

“If the conversation is really only about the infrastructure, then we have missed the opportunity to have the larger conversation about how we choose to manage the world,” he adds. “And that is at the heart of the community design movement.”

ALAINA MABASO is a Philadelphia-based freelance writer and the associate editor of BroadStreetReview.com, Philly’s hub for arts, culture and commentary. You can visit her at her blog, where fiction need not apply.