Four years ago, most folks in the Lehigh Valley were telling Ken Mohr, then the county’s Community and Economic Development Director, that a proposal to build a stadium for AAA minor league baseball was a waste of time and he shouldn’t stake resources or political capital on it.

Four years ago, most folks in the Lehigh Valley were telling Ken Mohr, then the county’s Community and Economic Development Director, that a proposal to build a stadium for AAA minor league baseball was a waste of time and he shouldn’t stake resources or political capital on it.

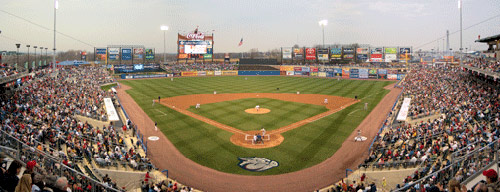

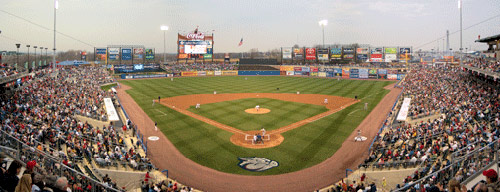

Despite its detractors, the stadium and its team, The Lehigh Valley Iron Pigs (AAA affiliate to the Philadelphia Phillies), have proven to be a resounding success for the region, becoming one of only six Minor League franchises to surpass the 600,000 mark for total attendance last year and raking in awards, accolades and revenue.

But four or five years ago, critics of the stadium were not without their reasons. The Lehigh Valley has had some trouble following through with large-scale entertainment venues over the years–like the proposed riverfront arena, the proposed arena at 9th and Hamilton in Allentown, and the partially built stadium in Williams Township. Just to name a few.

So what made the Iron Pigs fly?

The baseball stadium, now dubbed Coca-Cola Park, was different, says Mohr, because a few crucial elements made the project stand out from the crowd of similar-sounding proposals.

During his tenure as Community and Economic Development Director, about five high-end development proposals would come across Mohr’s desk each year–everything from indoor tennis courts to hotel conference centers to multi-purpose entertainment venues. “Sorting the wheat from the chafe is always the most difficult,” he says.

“All of these types of things, whether it be a minor league baseball team or an ice hockey team or whatever, all of them can succeed if they have a large enough market and they’ve got an operator who really knows what they’re doing,” Mohr says.

In the case of Coca-Cola Park, the operators were Craig Stein and Joe Finley–a pair Mohr says had very specific ideas about how to make the stadium successful and who wanted things done a certain way. “These guys were operators who were recognized pretty much as being the top in their field, quite often by their competitors.”

In the case of Coca-Cola Park, the operators were Craig Stein and Joe Finley–a pair Mohr says had very specific ideas about how to make the stadium successful and who wanted things done a certain way. “These guys were operators who were recognized pretty much as being the top in their field, quite often by their competitors.”

But having the right guys for the job was only one of the obstacles facing Mohr.

“Once you have operators who know what they’re doing, finding the local [capital] match is the most difficult part,” Mohr says.

One of the major problems, he explains, is that these types of development projects rarely make enough money to cover the full capital costs. Some kind of public entity inevitably must step in to subsidize the initial construction.

And that’s the big sticking point, says Mohr. Most local governments are in favor of high-end entertainment developments, but few are willing to put up the cash–or they can’t figure out how to come up with their share of the capital.

After considering about twenty different sources of revenue, Mohr and other key players–such as former Lehigh County Executive Jane Ervin–agreed that increasing the county’s hotel tax by half a percent, from three and a half to four percent, was the best way to come up with their share of capital. To do this, however, required an act of the state legislature and subsequent action by county commissioners; everyone had to be on board.

“No one person played a small role, everybody played a big role,” Mohr says. “We needed to get all the local state legislators either to go along, or at least not try and destroy the project… Once the state gave us the ability to increase the hotel tax, we needed the county commissioners to actually increase it, and we needed to bring along a lot of people in the process.”

The capital for the stadium ended up coming from three sources: state government grants, Lehigh County’s increased hotel tax–which remains well below the rate in other areas of Pennsylvania–and the team’s owners, Stein and Finley.

“You really need patience and political will,” he says. “In this case, it was the county executive, Jane Ervin, she’s the one who wanted to do this, which was not popular here at all because so many other efforts like this had tried and failed in the Lehigh Valley.”

But once the ball got rolling, the region quickly saw positive ripple effects: property values around the stadium increased by 300 percent after the announcement that funding had been secured, and the construction of the ballpark itself brought an influx of hundreds of construction with a payroll of more than $17 million.

To Mohr, the entire process is instructive for communities that want to pursue large-scale development projects. Three things are essential, he says: committed leadership, professional management and regional cooperation.

“It goes to show that these things can be accomplished if they are done in a way that takes into consideration the market, the operators, the source of revenue, and at the same time cooperates with state and local officials,” Mohr says. “But it also takes the political will of someone who’s wiling to put themselves out there and say ‘this is something I want to do and I’m willing to stake my political career on it.'”

John Davidson is the Managing Editor of Keystone Edge. Send feedback here.

To receive Keystone Edge free every week, click here.

Photos:

The Coca Cola Stadium

Jane Ervin with Ken Mohr at the stadium

All Photographs Courtesy of Ken Mohr

To receive Keystone Edge free every week, click here.