Every day but Sunday, Casey Spacht's phone starts ringing early — sometimes around 3 o'clock in the morning. He knows who's calling: It's one of the 83 “member farmers” of Lancaster Farm Fresh Cooperative (LFFC), the growers' coalition he's managed for seven years, checking in with daily output predictions.

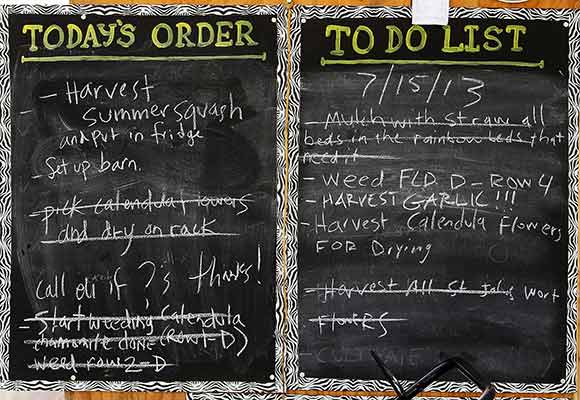

Matching these ever-fluctuating estimates with the needs of wholesale clients and the co-op's CSA members (“community supported agriculture” subscribers pay a seasonal fee and receive weekly boxes of fresh produce), Spacht circles back to each farm with firm figures. The product gets harvested, then shuttled to LFFC's Leola, Pa., warehouse, where, from late night until early morning, it's sorted, packaged and sent up and down the East Coast. It's a remarkably tight setup — one that ensures most customers receive organically grown Lancaster County fruits and vegetables less than 24 hours after they're picked.

Yes, LFFC is efficient, but it's more than just a conduit connecting fields with kitchens. It's also a means of collective agricultural empowerment, a system that streamlines a complicated process and allows small family farmers to do what they do best: farm.

Spacht, who has his own growing operation, Lancaster Farmacy, in addition to running point for LFFC, has long been dialed into the cooperative concept.

“I've always loved the whole co-op model,” he says. “People can really band together and make it work for themselves.” A Lancaster County native who grew up about eight miles from co-op HQ, Spacht first left the Commonwealth in his late teens, riding a bicycle all the way down to Athens, Georgia to live and work. In 1998, Spacht headed to Tennessee, where he managed the Knoxville Community Food Cooperative. After spending time in Colorado and Canada, and touring the country with friends' bands, he landed in western Pennsylvania in 2003, heading home permanently two years later.

At an early meeting — it literally took place inside a barn — a small group of nine farmers presented him with an idea: They hoped to form an organic growers' co-op, and they wanted Spacht to oversee it. Originally more comfortable with an outside consultant role, Spacht declined the offer multiple times before signing up in late 2005. LFFC began operating officially in May 2006.

“When we first started, we didn't really turn away farmers,” says Spacht. “If you were certified organic and you had product, come join. Now, we have a special process. We can't just take everybody.”

Those who do make the cut have their products shuttled by one of LFFC's 13 vehicles, a fleet based out of the co-op's 9,000-square-foot processing warehouse. (Since a majority of the co-op's members are Amish, the trucking company is technically a separate entity from the co-op.) LFFC currently employs close to 60 workers in addition to its farmers.

Though more selective than ever, LFFC's schematics remain simple. Members all stand on equal footing within the co-op, regardless of volume.

“We might send in 20 or 30 cases of asparagus, and another farmer might be sending in 50 cases a week. But both have the same stake in the company,” explains Spacht. Members who operated independently prior to joining are required to transfer all existing customers to LFFC, meaning all transactions must go through the co-op exclusively. No side sales. This is largely how the co-op's reach — which has grown in scope to include meats, eggs and dairy in addition to fruits and vegetables — has spread north to New England and south to Virginia and Washington, D.C. There is an annual membership fee; if profits exceed payouts and operating costs at the end of the year, the difference is divvied up and returned to the farmers.

“We had big wholesalers, but those guys jerked us around if they wanted to,” recalls Aaron Zook, a founding LFFC member. He wanted to bolster margins, individually and collectively, by teaming up with fellow growers. The son of a dairy farmer, Zook began developing Riverview Farm in 2004. This summer, he's anticipating large crops of heirloom tomatoes, beets and peppers, and he's already begun seeding squash, parsnips and other colder-weather crops for the fall — all raised under strict organic guidelines, with no pesticides or chemicals.

Sheer paucity of time was another factor motivating the founding of LFFC. Without co-op association, family farms like Zook's — most LFFC members maintain around 10 to 15 acres — must market and move product on their own, eating up valuable hours that could be spent in the dirt.

“Everyone always talks about a farmer being close to the land,” says Spacht. “But in reality, they also have to be on the road, and marketing, and on the phone, doing a lot of paperwork. We cut all that out. We make it easier so that they can be connected with the land that they're growing on.”

Healthy Harvest's Amos Stolzfus, who grew up farming for his father, cites this freedom as the biggest benefit of LFFC membership.

“All we have to do is grow a good, healthy, nutritious product and it's sold before we pick it,” says the farmer, a relatively new member growing strawberries, green beans, watermelon and tomatoes. “You don't have the headaches of selling it. Back when I was working for my dad, he spent half the time on the phone trying to get rid of his produce.” Membership also allows Stolzfus to spend more time at home with his wife and five children.

“Once a farmer joins, there's a whole business plan that's already set up,” says Spacht. “And we know it works.”

It works on the receiving end, too. Rich Landau first began working with Spacht when he and wife/partner Kate Jacoby ran Horizons off South Street in Philadelphia. The couple closed that vegan restaurant to open Center City's acclaimed Vedge, also fully vegan, in 2011. Landau says purveyors like LFFC are what inspired him to move away from proteins like seitan and tempeh to focus more on seasonal vegetables.

The seed was planted years back at Horizons, when Spacht dropped off a care package of his best products for Landau to test out.

“I'd do anything for a picture of the expression on my face when I opened this box of vegetables,” the chef recalls. “It was like I'd never seen vegetables before I'd seen these things. Vegetables the way vegetables are supposed to be. It blew my mind.”

LFFC's rigorous requirements are to thank for the consistency of their products. “One of the challenges [for the] co-op as a whole is for everybody to be up to the same quality standards,” says Spacht.

Farm Fresh vegetables are prominent on Vedge's current menu — take Landau's dish of French breakfast radishes, baby white cucumbers and fava beans, tossed in tarragon vinaigrette over saffron aioli; or tatsoi, a Chinese green, in a shitake mushroom dashi broth. “You get one step closer to the dirt with guys like Casey,” says Landau. “It's a whole other level of freshness and quality.”

Spacht's willingness to grow rare specialty vegetables also sets LFFC apart. “With [other purveyors], you say, 'Can you get me this?'” says Landau. “With Casey, you say, 'Can you grow me this?'”

Spacht often takes on more esoteric challenges personally: At his farm, he's tending to bergamots, cardoons, jicama and purple sweet potatoes.

LFFC's growth has been rapid, bringing its own share of challenges. The co-op has sized out of its current warehouse and is looking to secure a new space four to five times larger.

“We thought we would be in there for 20 years, but it's jam-packed,” says Zook. “People say we don't have a healthy growth rate — it's way too fast. I can understand, [but] we depend on it. It's either we do what it takes or have the thing go backwards.”

“We do this for the next generation,” explains Spacht. “One of the big accomplishments I feel we've made as a co-op is now [we have] three farmers that are sons of existing farmers in the co-op. There are farmers making a livelihood off being in the co-op that bought farms for their sons — and now they're making their livelihoods on them.”

DREW LAZOR is a native Marylander and longtime Philadelphian who writes about food, drink, movies and music locally and nationally. Contact him at andrewlazor@gmail.com or on Twitter (@drewlazor).

Photographs by CHRIS KNIGHT