A key to obesity, heart disease and other chronic diet-related ailments could be as tiny as a pore on the membrane of our taste cells. That's what a recent experiment led by Dr. Michael Tordoff, a taste biologist at the Monell Chemical Senses Center in University City, has apparently revealed.

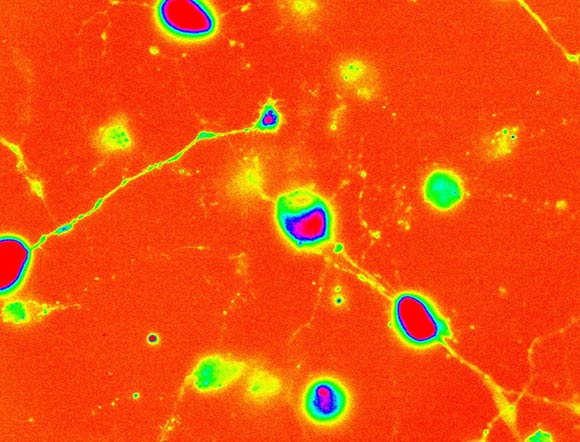

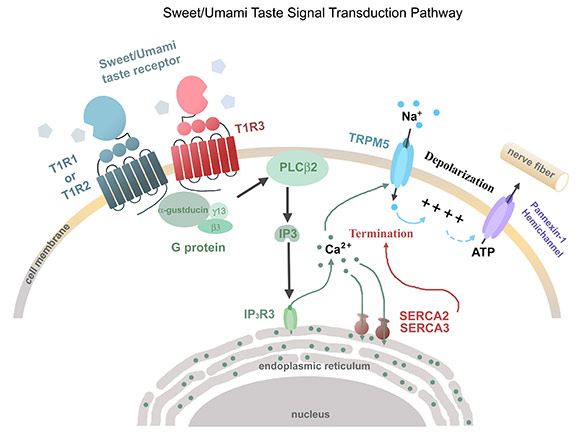

Tordoff's field, taste transduction, attempts to explain the physiological pathway from our tongues to our brains. The discovery of CALHM1, dubbed the “missing link” in taste perception (reported in the March issue of the science journal Nature) has great implications for developing drugs to treat obesity and related diseases.

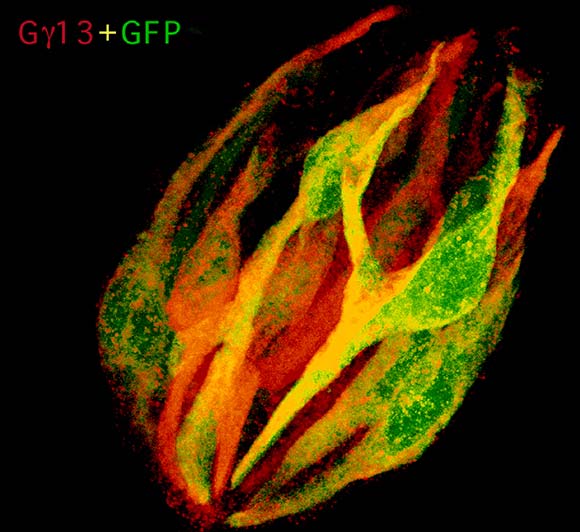

The study revealed a tiny opening or “channel” (since named CALHM1) responsible for enabling ATP — the neurotransmitter that signals sweet, bitter and umami tastes — to move from one type of taste cell to another and eventually to the brain. Mice lacking the channel maintained normal activities, including eating, they just ate a little less.

“If you very carefully put some sugar onto the active end of the taste cell, you can actually see the ATP being released out the other end if they have these channels,” says Tordoff. “If they don't, or if these channels are blocked, the ATP is not released.”

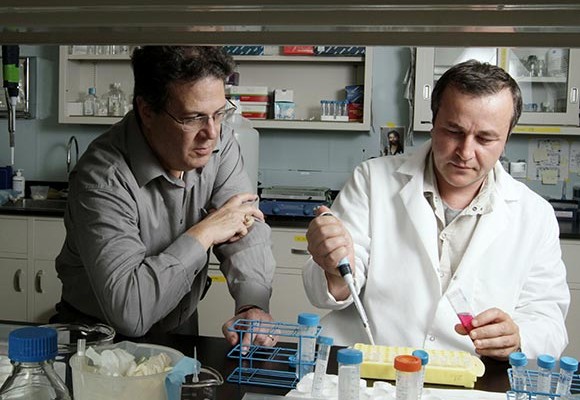

Taste transduction is one of the many fields experiencing breakthroughs at Monell. Their two adjioning buildings occupy 80,000 square feet, on the campus of the University City Science Center, and host nearly 60 PhD-level scientists from across the world in a range of disciplines including sensory science, physiology, chemistry and molecular genetics.

With the exception of molecular biology, Monell (a nonprofit which receives funding from National Institutes of Health as well as food, pharma, cosmetic, and household product corporations) has no departments. While the center is strictly involved in the production of knowledge (as opposed to applications), their 45-year history of cross-disciplinary collaboration — often including work with Drexel and Penn — has yielded a laundry list of scientific milestones. Their work has influenced the fields of diagnostics, food production, immunity, pest and animal control, physical and mental health treatment, as well as our understanding of individual genetics, gender and human sexuality.

Taste and smell are chronically overlooked by the greater scientific community. Dr. Morley Kare, a Cornell veterinary scientist, founded Monell in 1967, through a $1 million contribution from Ambrose Monell Foundation. He established the first location in 1968, at 25th and Locust in Center City, as part of Penn (they moved to their current University City location in 1971 and became independent in 1971). His work in animal nutrition revealed that science, while committed to understanding the eyes and ears, had long neglected the nose and tongue.

To date, Monell is the only institute devoted exclusively to life's original sensory system.

“When we were little blobs floating around the primordial sea, the way we learned about the environment around us was by sensing chemicals,” says Leslie Stein, director of Science Communications at Monell. “Those chemicals told us if there was food nearby — or if there was a potential mate.”

Due to their primal origins, receptors in our nose (which effect taste as well as smell) are directly connected to the part of the brain associated with emotion and memory. Sight and hearing, by contrast, visit several other brain compartments first. As such, the sense of smell plays a significant role in everything from detecting harmful chemicals to sparking the nostalgia associated with grandma's cookies to triggering post-traumatic stress disorder.

“Attraction versus repulsion — that's what taste and smell are all about,” says Stein. “As we've evolved, we've become more dependent on sight and hearing, but our emotions and memory are much more tied to taste and smell.”

These senses also supply endless genetic information. Dr. Danielle Reed, a behavioral geneticist at Monell, keeps a drawer of chemical samples and, based on a person's ability to taste or smell these specific compounds, she can detect receptors in their immune system. If a person can't taste the bitter compound available in broccoli, they are likely lacking the TAS2R38 receptor and their immune system is less capable of detecting certain bacteria. They are also more apt to enjoy the taste of alcohol and therefore more prone to alcoholism.

Dr. Charles Wysocki, a neuroscientist, has been contributing to Monell's 30-year study on the olfactory imprint — the theory that individuals' sense of smell is as unique as their thumbprint. His research has decoded gender behavior and sexual orientation based on the olfactory system. Some of his studies have shown that heterosexual women have the ability to smell a good mate (men and homosexual women appear to lack this ability). The hormonal changes that result from birth control can interfere, resulting in biologically incompatible partnering, a theoretical contributor to increased divorce rate.

By decoding the molecular structure, molecular biologist Joel Mainland is helping reveal the basic-building blocks of odor at Monell. These discoveries may one day inform an olfactory “printer” that can recreate countless smells via select molecules. The information could also be used for diagnostic devises that recognize certain diseases by their odor — something dogs can already do.

Of course, one of the most urgent reasons to study smell and taste is the the nation's rising rates of obesity, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. In a world of readily available foods, the once-vital role taste and smell play in differentiating nutrients from poison is leading to over consumption. According to the Center for Disease Control, 35.5 percent of american adults are obese as of 2010 (that number was 27.5 percent in 2000). Additionally, diabetes cases rose from 1 percent to 7 percent of U.S. population between 1960 and 2010 and 1/3 of adults have high blood pressure.

Through further studies, scientists hope to create substitutes, blockers and drugs that help our sensory system adjust to the 21st century food landscape and decrease incidents of dietary disease.

“If we can understand why we like sodium — what are the physiological underpinnings — and if we can understand how sodium taste itself works, we can possibly come up with salty taste-modifiers or salty taste-replacers,” says Stein. “The more we can understand how salty taste works, the more we can actually help people who need to reduce their salt intake.”

To that end, Monell is continuing with studies like Tordoff's, plus analyzing taste stem cells and examining the connection between a person's saliva and their metabolism. They're also involved in studies related to the development of nutritional habits. This includes research by Dr. Julie Mennella, a biopsychologist who has found that breast milk — and the specific flavors the mother consumes during lactation — can lay the groundwork for dietary decisions made across a person's lifetime.

According to Tordoff, the fact that the greater scientific community recognizes only five tastes — salty, bitter, sweet, sour and umami — shows there is still a lot to be discovered.

“Water, fat and starch are also tastes,” he says. “[The five tastes] is one of those things the Greeks told us and nobody's really bothered to question it — some people would say there are dozens.”

The University City Science Center has partnered with Keystone Edge to showcase innovation in Greater Philadelphia through the “Inventing the Future” series.

DANA HENRY is Innovation & Jobs News editor for sister publication Flying Kite. Send feedback here.