There’s a place in business for concepts that can’t find funding to reach production. It’s called the “Valley of Death” and it’s where the carcasses of good ideas go to die.

There’s a place in business for concepts that can’t find funding to reach production. It’s called the “Valley of Death” and it’s where the carcasses of good ideas go to die.

Consider, then, the Pennsylvania NanoMaterials Commercialization Center an oasis in the nanotechnology desert, or–perhaps more aptly–a bridge over the harsh landscape of commercialization.

The center, based in Pittsburgh, is designed to fund nanotechnology startups that need money to develop promising research into marketable products. “We’re very early stage capital investors where venture capitalists won’t go,” says Alan Brown, the center’s executive director.

Many ideas are born through research dollars at institutions and universities, but the funding often dries up once the experimenting ends. From there to the market lies the valley that the nano center bridges.

The idea is equally a boon to large corporations looking to breathe new life into their product lines. In fact, that’s how the center was born in 2006.

“The center came out of, really, a discussion with major companies in southwestern Pennsylvania,” Brown says. “They were looking for ways that new technology could revitalize these companies. A lot of these large corporations, they have considerably downsized their internal R&D.”

Instead, such companies have employees “to find innovation they can buy, license or partner” with to develop, Brown said, and the center’s niche is to facilitate that.

Nanotechnology is a broad category of innovations that often inspires thoughts of “little nano robots crawling around in our bodies and cleaning stuff,” Brown says, but what’s being done now are small breakthroughs on the molecular level for “materials, any kind of materials,” from polymers to powders to carbon nanotubes, that change or enhance the materials’ properties.

Nanotechnology is a broad category of innovations that often inspires thoughts of “little nano robots crawling around in our bodies and cleaning stuff,” Brown says, but what’s being done now are small breakthroughs on the molecular level for “materials, any kind of materials,” from polymers to powders to carbon nanotubes, that change or enhance the materials’ properties.

Take, for example, the work at Y-Carbon, a startup based in King of Prussia that’s creating commercial applications for porous carbon research from Drexel University’s Nanotechnology Institute.

While a grad student at the university, Ranjan Dash figured out how to use metal carbides to control the pore sizes of carbon, thus tailoring the carbon’s properties for specific uses, such as increasing the energy storage in supercapacitors and hydrogen storage. He founded the company in 2004, becoming its chief technology officer, but the company didn’t become active until 2007. In 2008, the company applied for funding from the nano center and received $250,000 to build a prototype supercapacitor with twice the usual storage for a similar production price. Using that, the company is now raising capital to build an assembly line.

The company credits the nano center with shaving up to two years off its development timeline, but it also benefited from the focus the center creates through its mandatory milestones.

Going forward, the company is interested in the center’s mentoring program, which links startups with large corporations. The relationship is mutually beneficial: startups provide the innovations while big businesses provide the money to get products to market.

Going forward, the company is interested in the center’s mentoring program, which links startups with large corporations. The relationship is mutually beneficial: startups provide the innovations while big businesses provide the money to get products to market.

“In this marketplace today, it’s difficult for early-stage companies to raise capital to turn ideas into concepts,” says James Horan, Y-Carbon’s chief executive officer.

The nano center boasts other evolving success stories–such as turning research at Carnegie Mellon University into how geckos grip seemingly smooth surfaces–but it has also witnessed failures.

“As you can imagine, this is a numbers game,” Brown says.

Over the past three years, the center, which has three fulltime employees, has received nearly 100 proposals. A technology advisory committee of roughly 20 members reviews the ideas, which must be from Pennsylvania companies, based on the funding needed compared to the potential value, and submits the top proposals to the center’s board. From there, companies receive at least $150,000.

“Anything less than that, and you get less of a benefit,” Brown says.

So far, 17 projects from 15 companies have been funded. “Our statistics so far, we’ve had two companies that have failed out of that portfolio, but we have probably 3 or 4 companies who are doing very well,” Brown says.

The funding comes from a variety of sources, including the state Ben Franklin Technology Partners, foundational investments and the military. The funding helps companies like Strategic Polymer Sciences, Inc. transfer from research to marketing mode. The State College-based startup uses research developed at Penn State University that wraps metals with engineered polymer films to increase the ability for capacitors to store energy while decreasing their size.

The funding comes from a variety of sources, including the state Ben Franklin Technology Partners, foundational investments and the military. The funding helps companies like Strategic Polymer Sciences, Inc. transfer from research to marketing mode. The State College-based startup uses research developed at Penn State University that wraps metals with engineered polymer films to increase the ability for capacitors to store energy while decreasing their size.

According to the company, capacitors take up as much as 50 percent of a device’s volume, and its film capacitors can provide the same amount of energy at 50-percent less volume. In March, the company plans to bring that technology to market, according to Dean Anderson, the company’s director of operations.

SPS received funding from the Small Business Innovation Research program to research the technology, but–like most research funding–it didn’t cover bringing the products to market. A $200,000 grant from the nano center helped SPS develop capacitors for a smaller plantable heart defibrillator for which it’s landed a collaboration with a “Tier-I medical company,” Anderson said. The company is also seeking outside funding for its miniaturization technology to develop pulse-energy weapons, hybrid-electric vehicles and electricity transmission.

Going forward, the center hopes to interact more with private investors.

“We think we can help them by basically showcasing these companies so (investors) can have a much earlier look at what they’re going to invest in,” Brown says. “We would like to hand these small companies off to private investors.”

Beyond that, the center is looking for more funding it can hand out because as technology advances, ever more ideas spring up that could be worth funding.

“The impact that we have is obviously proportional to the size of the budget,” Brown says. “We turn away more projects than we fund.”

Rory Sweeney writes on energy and the environment when he’s paid to and sits

around talking about them when he’s not. Send feedback here.

To receive Keystone Edge free every week, click

here.

Photos:

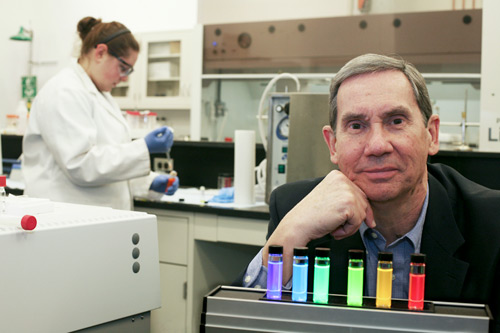

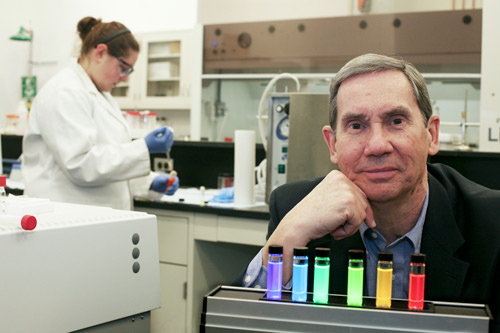

Dr. Alan Brown, the director of the PA NanoMaterials Commercialization Center, at the Crystalplex laboratories. (Heather Mull)

Crystalplex shows vials of colored liquid called Quantum Dots. They are activated under UV

light. (Heather Mull)

Dean Anderson, Ph.D., Director of Operations for Strategic Polymer Sciences, Inc. (Brad Bower)

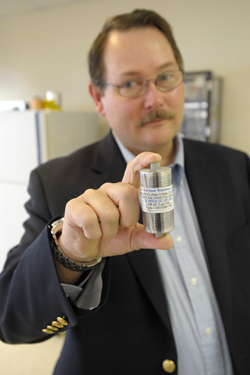

Anderson holds a sample roll of the wound capacitor film they are developing at their State College lab (Brad Bower)

Shihai Zhang, Ph.D., Director of Engineering, left, and Anderson examine a roll of the wound capacitor film. (Brad Bower)