This July, Pittsburgh may enjoy the fruits of an artwork fourteen years in the making. The Industrial Arts Co-op (perhaps best known as the artists who brought you the Rankin Deer) has created a formidable public sculpture to commemorate the laborers of steel. Commissioned by the city of Pittsburgh in 1997, the piece features two steelworkers towering over a hot metal ladle; the scale references the oversized grandeur of the steel mills while decidedly placing emphasis on people over machines.

The ladle included in the sculpture is the genuine article, obtained from Casey Equipment, a Pittsburgh company that rescues and refurbishes such industrial items. But the 18-foot high abstract workers–fashioned from local I-beams–have been painstakingly designed, assembled, welded, adjusted, bolted, grinded, and sandblasted by numerous members of the arts collective.

Since the mid 1990s, the Industrial Arts Co-op (IAC) has been repurposing Pittsburgh-area industrial discards–from early renegade uses of industrial sites, to the Brew House studio where they were based when this sculpture project began, to the I-beams (the steelworkers’ limbs) that were donated to them when the Hot Metal Bridge was being renovated.

Their Rankin Deer project (1997-98) succeeded in being built entirely of metal scraps found on the site where it still stands, the defunct Carrie Furnace. IAC co-founder and project manager Tim Kaulen explains that recycling and repurposing were in fact industry habits, citing that byproducts of the steel-making process like gasses were piped across the Hot Metal Bridge and used by the boiler house to fuel more production. The boiler house was the last building of the original Jones & Laughlin plant to be demolished (by steelworkers who had repurposed themselves into demolition contractors), and the “armor” adorning the sculpture’s laborers came from that building.

While the Rankin Deer speaks to the fate of an industrial shell being taken over by wildlife and fauna, the Southside Works Sculpture Project (its working title) will relocate hard-edged shapes and industry’s grand scale out of the steel environs and into a nature-friendly recreational park. The sculpture currently inhabits a Hazelwood industrial shed, formerly part of the LTV coke works. With the city's final approval granted, it will soon be transported across the Monongahela to the Southside Riverfront Park, just downstream from the Birmingham Bridge. This particular site was once a train yard for the Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad Company, whose freight cars served the steel, coke, and coal industries.

Ronald Baraff, curator at Rivers of Steel, doesn't underestimate the significance of the IAC's sculptural homage. “This city has tried to run away from its past. They said, 'We're not a Steel City anymore–look, we've cleaned up and transformed.' But you can't deny your past. The fact is, steel was a positive for Pittsburgh–it's what moved this region forward. Steel made us who we are.”

He sees the Southside sculpture as a way to help rectify that glossing-over and honor the laborers of Pittsburgh's mighty legacy: “This monument should have happened a long time ago.” He finds the IAC's sculpture “very unique” not only in its direct recycling of materials from the plants, but in depicting the workers in the midst of heavy physical activity.

Based on his visitors to the Rivers of Steel collections in Homestead, Baraff believes that the physicality of the sculptures will be a powerful draw. He encounters retired steelworkers who seek “anything that creates a connection back to the work that these men and women did, and especially something that is tangible, that creates a sense of place–something they can show their families. The [open hearth] stacks at the Waterfront have drawn an enormous number of visitors, even though they're only a small fraction of the plant that was at Homestead.”

I-beams and ladles aren't the only things the IAC has borrowed from the city's industrial past. Pittsburgh's promising present of flourishing non-profits is made possible in no small part by local industrial fortunes turned into grant monies. Foundation support for the Southside Works Sculpture Project has been substantial, including contributions from the Heinz Endowments, Pittsburgh Foundation, and a Pittsburgh 250 Community Connections Award.

Support includes the sculpture's closest neighbors as well. Rick Belloli of the South Side Local Development Company attests that South Side citizens have welcomed such a recognition of the neighborhood’s steel heritage, adding, “I think all of us in Pittsburgh think of ourselves as part of the steel community.”

Even the Industrial Arts Co-op holds echoes of the steel industry, as its large metal artworks demand collaboration and technical proficiency among members. Kaulen talks about wanting to pass on such skills as metal-working and public art facilitation as he shepherds a younger generation of Co-op artists. He hopes the IAC can continue to create opportunities and show young artists that “Pittsburgh is a great place to hone art skills; it's still a place where you can think big and do the things you want to do.” But he also looks forward to the day that this steel sculpture “is no longer an art project, but can become a civic icon for the working person. Not just something for 'the art people.' “

KAREN LILLIS is a novelist and a freelance writer. She is currently at work on a memoir about her years working in a New York indie bookstore. Send feedback here.

Photographs copyright Brian Cohen

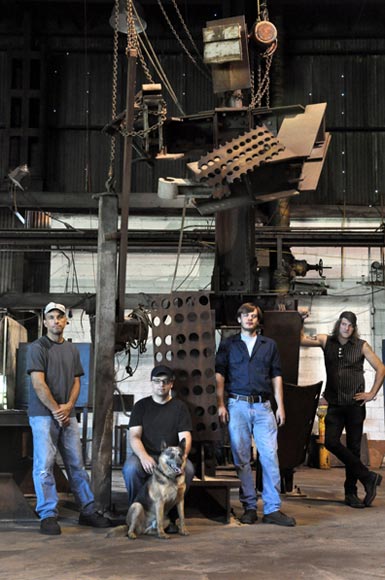

Group shot, from left: Tim Kaulen, Joe Kulik, Eli, Joe Messalle, Corey Lyons; Tim Kaulen; Ron Baraff.