If you see Ray Gant’s old, beat-up green Dodge van barreling toward you in North, South or West Philadelphia some day, you better steer clear.

Unless you’re ready to work.

“That’s all you want to do. You’ve got to hit stuff like this here,” Gant tells a college-aged young man as he shows the volunteer how to weedwack near the corner of Indiana Ave. and B St. in Kensington on an October Saturday morning as most people in Philadelphia were preparing for Hurricane Sandy.

“This is what you want to do young lady,” Gant instructs another student, showing her how to sweep up assorted trash that has been collecting on the sidewalk.

As Gant returns to the back of his van, the tools of his trade immediately become apparent. The Dodge is full of rakes, shovels, garbage pickers, gas containers, weed wackers and buckets of “Philly Anti-Graffiti Gray” paint.

More than two decades ago, Gant employed different tools in neighborhoods around North Philadelphia as a powerful drug dealer before getting busted in 1987 and doing 12 years in prison, including the first two years in solitary. For the last 10 years, however, Gant, 56, has literally been a Ray of Hope, the name of his non-profit project that he founded with area businessman and mentor Willard Bostock in 2002 and focuses on beautifying blighted neighborhoods.

“This has changed my spirit. It has been spiritual for me,” says Gant, 56. “It was like I finally found out where my place in life as at. It became something I love to do.”

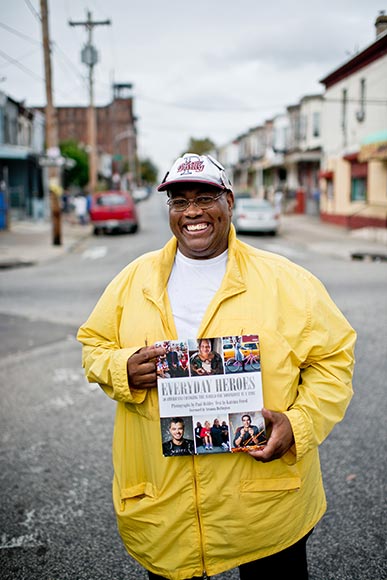

The Ray of Hope (ROH) Project recently became charged with its biggest contract — supervising the ongoing cleanup of the Frankford Ave. corridor in the Northeast. Perhaps the biggest news is that Gant is featured in a recently released book called “Everyday Heroes: 50 Americans Changing the World One Nonprofit at a Time.” Described by Amazon as a “groundbreaking book profiling some of America’s leading social entrepreneurs,” the book features photos by noted American photographer Paul Mobley and also two other more well-known local groups, Alex’s Lemonade Stand and Back on My Feet.

Gant is hosting a book-signing on Saturday, Nov. 17 from 11 a.m-2 p.m. at McPherson Library in Kensington, in part to help promote the facility’s expanded hours. Signed copies of the hardcover, coffee-table sized book cost $45 and proceeds will support ROH.

It’s also fitting the book-signing is held here considering Gant’s impact right outside the library. ROH started cleaning up McPherson Square about two years ago and its improved condition directly led to it getting a Kaboom playground donation on a patch of land once known as “Needle Park” because of its drug activity..

On this recent Saturday when Gant is supervising some two dozen young volunteers, it’s actually hard to pinpoint his group. Coming west down Indiana Ave, there’s a large group of people cleaning up Hissey Playground — another one of ROH’s previous projects. That helped raise Hissey’s profile and now United Way volunteers are organizing the cleanup there.

That means Gant can focus elsewhere, and he’s just down the block with his collaborators. These groups of volunteers are from Temple University and the local arm of national nonprofit BuildOn, and Gant has them working hard. Gant reels off most every college in the region, naming all the groups he has partnered with. He says he identifies needy neighborhoods with his own eyes, simply driving by and making notes. He then finds neighborhood leaders to partner with and the beautification collaboration begins.

“People are territorial,” he says. “They don’t want people coming into their neighborhood and telling them what to do.”

Gant does it all in places that intimidate most people, either by the sheer scale of the cleanup or the various elements that have conspired to bring the neighborhood down. ROH survives on modest fundraisers, individual contributions and various activities money from the City of Philadelphia. Gant has forged partnerships with the city’s UnLitter Us program and also works closely with the Philadelphia Streets Department.

Gant, a Frankford resident since 2001, is excited about the future, particularly in his own neighborhood. His contract to clean up the historic commercial corridor there will keep him busy for awhile. Besides that, he sees a different Frankford than many.

“I don’t see real big problems in Frankford. I mean, the crime can be less, but in Frankford you’ve still got people who live in that community that have a real unity that you can see.

“You see different people come out to community meetings and doing work. You see now they’ve got some foot patrol (police officers) on Frankford Ave. People care about Frankford.”

Gant’s aim is not to remove every last cigarette butt or wayward weed. Simply put, he wants to have a “good cleanup” that both volunteers and the community can take pride in. He also believes his approach can be a job creator in neighborhoods that need more employment opportunities.

“I come out and offer beautification in the hope that people in the community will come out and engage with the process themselves,” says Gant. “I believe beautification can make communities healthier and safer.”

JOE PETRUCCI is managing editor of Flying Kite. Send feedback here.