When Luzerne County veterinarian Doug Ayers decided to expand his clinic in 2007, virtually everything he installed was state-of-the-art, right down the energy-efficient concrete foundation. His goal with the insulated concrete forms was to be more environmentally conscious, but it certainly didn’t hurt that they were going to keep some more green in his pocket as well.

When Luzerne County veterinarian Doug Ayers decided to expand his clinic in 2007, virtually everything he installed was state-of-the-art, right down the energy-efficient concrete foundation. His goal with the insulated concrete forms was to be more environmentally conscious, but it certainly didn’t hurt that they were going to keep some more green in his pocket as well.

The insulated concrete forms, known as ICF, are part of a relatively new offshoot in the building industry that’s gaining popularity. Eschewing the usual cinderblock or poured-in-place concrete foundations and wood-framed homes, the new concrete construction options combine a range of features that can withstand hurricanes, won’t burn, stay dry, install quickly and, thanks to designed-in insulation, save energy and therefore will save money–for centuries.

For construction workers used to conventional methods, work on Ayers’ clinic no doubt began somewhat oddly, with large, interlocking boards of polystyrene foam setting the outline of the foundation and another wall of foam setting an inner perimeter. The walls would be used as the forms to pour and set concrete walls, but the innovative part about the ICF process is that the foam forms are never removed; they remain in place to create an airtight, insulated seal.

ICF can be used in residential settings as well, where it’s driven by two goals: structural durability and energy efficiency, according to Kenneth Krank, who represents the Pennsylvania Aggregates & Concrete Association.

ICF can be used in residential settings as well, where it’s driven by two goals: structural durability and energy efficiency, according to Kenneth Krank, who represents the Pennsylvania Aggregates & Concrete Association.

“Certainly on the residential market, I think when people get concerned about energy costs, that’s what gets people thinking about an ICF home,” he says.

But ICF has the downside of a lengthy installation time and a lack of control of the site conditions, which could affect the quality of the finished concrete. New Holland-based Superior Walls claims to solve those problems by producing all its concrete forms in 19 quality-controlled factories throughout the eastern half of the country. Cured to a strength of 5,000 pounds per square inch, the concrete is touted by the company as virtually impervious to moisture. The foam insulation exists only on the inside of the wall, so the exterior doesn’t require a durable finish, and each section is outfitted with steel studs to speed interior finishing. The walls, built to user-defined specifications for windows, doorways and exterior finishing attachments, are then transported to the site and installed immediately.

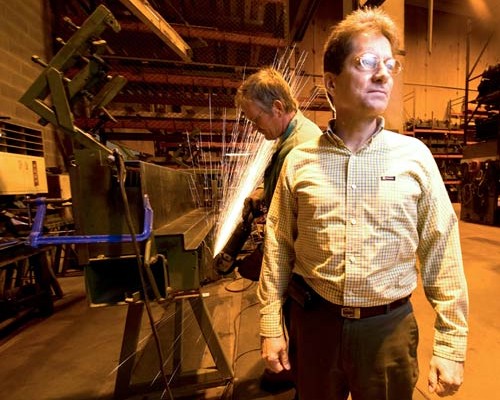

“The typical home (installation) today is less than a day. So that takes weather out of the equation–is it a hot day, is it a cold day,” Superior President Jim Costello says. “Our crew may be on site five, six, seven hours, and you’re done. And in that time, you’re just getting your equipment set up for the other” varieties of concrete construction.

The speed of installation was a major factor in architect and engineer Michelle Dempsey’s decision to use Superior Walls instead of traditional ICF for a client in Northeastern Pennsylvania.

“They’re both newer systems. They’ve been tried and true at this point that I felt comfortable with looking at both of them,” she says. “I did a lot of research–lawsuits, anything. Everybody who has Superior Walls has been happy with it. They said any problems have been with installation… It edged out the ICF in terms of functionality and speed.”

According to Dempsey, the extra cost of the Superior Walls “is a wash because they go in so quickly,” she says. And while concerns do exist with the durability of joints between the pieces and the lack of a footer, Dempsey said they were offset by other advantages, such as zero onsite waste to haul away, roughly 50 percent less concrete used, and the energy efficiency that the forms, combined with other insulation, can create.

According to Dempsey, the extra cost of the Superior Walls “is a wash because they go in so quickly,” she says. And while concerns do exist with the durability of joints between the pieces and the lack of a footer, Dempsey said they were offset by other advantages, such as zero onsite waste to haul away, roughly 50 percent less concrete used, and the energy efficiency that the forms, combined with other insulation, can create.

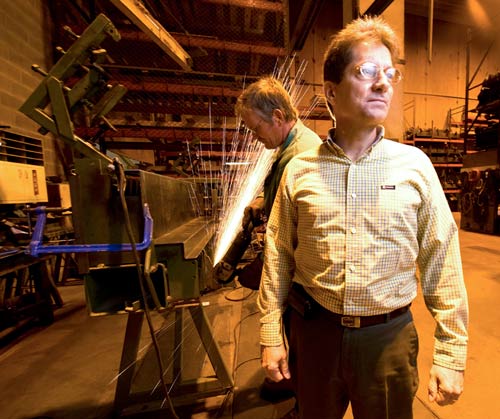

But according to representatives of Dryvit “outsulation,” the best way to conserve energy is to insulate outside: “Test after test, [scientists at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory] found the best place to put your insulation is on the exterior of the wall,” says Phil Neff, who works at Birdsboro-based Manning Materials.

Manning distributes Dryvit, a multi-layered exterior siding designed to wick moisture away from the structure and cut off energy-sapping thermal bridging by insulating the entire building. The product works wells with ICF, a brand of which Manning also distributes, because it provides a finish that can imitate various materials, including brick, stucco or stone.

The product is becoming popular with retrofits of drafty old churches because it can replicate the original exterior while increasing the R-value (the rating of how insulating a material is; its resistance to heat flow) by 400 percent and reducing energy cost some 40 percent, says Michael LeRoy, the northeast region’s sales manager.

“If you put it on the outside, it’s putting a big blanket over the whole house,” he says.

Dempsey noted some concerns with the product’s durability, but Neff and LeRoy said it can take hits from a hammer, and it be repaired easily, anyway.

As energy-use awareness continues to rise, the experts expect that demand for alternative construction options that maximize energy conservation will rise as well. And they understand that the image they cultivate now will affect that rise.

“We’re conscientious of the fact that the homes we will be build today will still be standing several centuries from now,” says Costello. “It’s kind of like Smuckers–with a name like Superior, it’d better be good.”

Rory Sweeney writes on energy and the environment when he’s paid to and sits around talking about them when he’s not. Send feedback here.

To receive Keystone Edge free every week, click here.

Photos :

Jim Costello President of Superior Walls (Glenn Usdin)

Phil Neff, vice president of sales with the rack of Dryvit product at the Manning Materials facility ( Brad Bower )

DryVit products ready for shipment ( Brad Bower )