In a century that embraces a knowledge-based economy, it can be easy to forget that thousands still receive paychecks for making tangible things.

Manufacturing remains Pennsylvania's largest industry. A February report from Cleveland State University found that in 2008, it comprised 13.6 percent of all economic output from Pennsylvania, beating real estate, health care, government and professional services.

The report, commissioned by the Pennsylvania Industrial Resource Center Network, found that more than 643,000 people worked for state manufacturers. The sector paid a respectable average salary of about $52,000.

The only way these businesses continue to thrive is by becoming more advanced. John Lloyd, president and CEO of MANTEC, a south-central PA nonprofit that serves manufacturers, says they must be distinctive to compete. That can mean making a cutting-edge product or making standard products in a new, efficient way. That often means being more flexible with customers and taking smaller orders. Robots and computer systems can automate some steps, track production and measure stores of supplies.

The idea of “lean manufacturing” is also becoming much more prominent. Basically, this means finding how to put people to work more efficiently. “It's a systematic way to eliminate waste,” Lloyd explains. “It can be wasted time, waste space, wasted inventory.”

Here are two companies blossoming in this new environment.

Topflight: More than stickers

Saying Topflight makes labels is like saying Julia Child made lunch.

“A lot of times people think of labels as a sticker, like you get in kindergarten,” says Patty Britton, VP of business development at the company in Glen Rock, south of York. Labels made by its 135 employees can be found on makeup, pill bottles and power drills. But a label's capabilities go far beyond telling a customer what's in a container and how to use it.

Companies come to Topflight for solutions to challenges like the battle to keep counterfeit products off store shelves. Some of its labels are embedded with tiny radio-frequency chips that can identify where a product was made and what country it's intended to be sold in. Customers can also mark products as theirs with labels that contain markings or lettering so small it can only be identified through a magnifying glass.

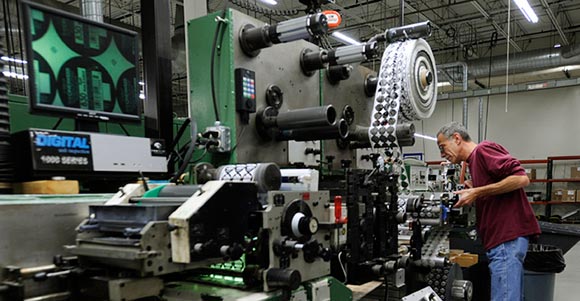

“Every single part we create is custom,” Britton says. Topflight's seven-member research and development staff can spend as much as two years perfecting a new label-making innovation.

The company's latest offerings include tiny circuit boards that can be printed on plastic film or paper. Printing circuit boards isn't a novel idea, but new technology mixes ink with microscopic silver particles to print precise, unbroken patterns that conduct electricity. These circuit boards can go into cell phones, medical diagnostic tests and other electronic devices that manufacturers want to be smaller, cheaper and faster.

Topflight actually started out building airplane parts during World War II, then designed printing presses for labels before

starting to make labels itself. Because of this history it has a few dozen different machines under its roof, some of which might only run twice a month. But that means the company can meet nearly any need a customer might have.

About seven years ago Topflight embraced lean manufacturing by placing new emphasis on running more efficiently and getting products out the door as quickly as possible. Now it ships nearly 4,000 orders per month, usually in a week or less. That's down from about two weeks of turnaround time before Topflight adopted a computer-based ordering system that tracks the entire process.

One consideration is how quickly workers can switch a machine from producing one order to another. That matters because Topflight takes comparatively small orders printed with such precision that it often takes longer to set up a machine than to make the actual labels. Director of Operations Glen Mattheu explains that Topflight increases efficiency by setting up all the tools a worker needs for each order at the right machine, eliminating time searching for the right equipment. That alone saved about 25 percent of the time needed to get ready to print an order.

That ability to quickly fulfill customers' precise needs is responsible for Topflight's success, Britton says. “We're not the cheapest, but when somebody needs something we don't balk,” she says.

Northway Industries: High-tech communication

A decade ago Northway Industries processed massive orders for wooden furniture and cabinetry. Trouble struck when two customers, who made up half the company's business, moved their contracts overseas. “They were receiving finished products for what we were buying materials for, so there was no way we could compete with that,” recalls company President Don O'Hora.

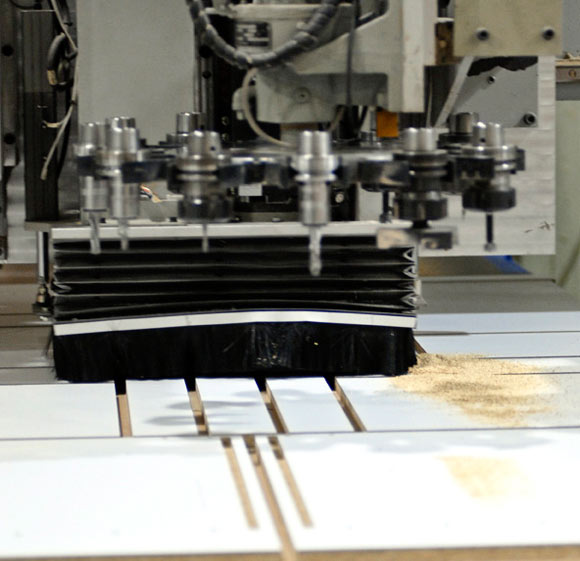

Northway had to figure out how to produce smaller orders for custom-built pieces and process them more quickly. That required different equipment that didn't take as long to set up – the more time workers spent preparing to fill an order, the larger that order had to be to make their time worthwhile. Today an average order might be for 50 or 100 cabinets.

“Ten years ago we'd say, 'You want that bookcase? You have to buy 1,000 of them,' ” O'Hora says. “Now we say, 'You want that bookcase? How many do you want?' “

Everything Northway makes starts as pieces of wood paneling that are laminated at the shop in the Central PA town of Middleburg. About half are sent out as complete pieces of furniture, while remaining orders are for pieces customers will assemble later. Shelves, desks and countertops produced at the facility between Harrisburg and Williamsport can be found in offices, schools and hotels.

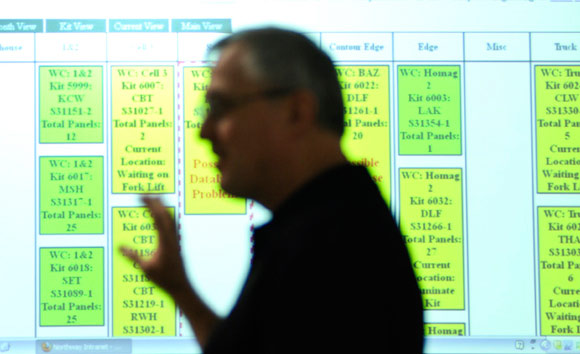

Northway follows orders on a Web-based system that tracks each email from customers and shows the upcoming production schedule. Robots put together precise kits for each panel needed for four hours' work on each machine. Even the forklifts are outfitted with computers that give drivers a prioritized list of which supplies need to be delivered where.

“Virtually everyone in our organization uses a computer and is interacting with advanced technology every day,” O'Hora says.

About 400 customers are registered in an online system that allows them to log in and see exactly how close their orders are to being filled. Northway's internal computer tracking and switch to processing fewer orders at a time – about 80 per week – means customers get their furniture in days instead of weeks, how it was before.

“What the customer sees is that we're a lot more responsive,” O'Hora says. “What we make is made in all corners of the world. It's not unique. It goes beyond just the product. The quality is important. The timely service is important.”

He emphasizes that most of the ideas that make Northway run better came from workers, not management. Even simple changes like arranging the right tools near each work station reduce the amount of time wasted. And the more efficiently manufacturers work, he says, the better off we all are.

“I'm a big believer that manufacturing is the key to our economic recovery,” O'Hora says. “For security and other reasons, we need to be making our own things.”

REBECCA VANDERMEULEN is a freelance writer who lives near Downingtown. As she tells friends out of state, that's between the cheesesteaks and the Amish. Send feedback here.

PHOTOS:

President and COO of Northway Industries Don O'Hora

A machine operator at Northway Industries stacks up an order that has been custom cut by a computer on the floor of the plant

Don O'Hora at his company's plant

A computerized router tool cuts a customer's order at the Northway Industries plant

At Northway Industries custom-cut pieces are fed into automated sanding machines

Topflight's Vice President of Business Development Patty Britton describes the new type of product they offer that of printed circuit board traces

A pressman on the floor with Topflight printers inspects a job running on one of the company's high speed presses

Director of Operations of Topflight, Glen Mattheu describes the new type of product work flow they put into play at their Glen Rock facility

All Photographs by BRAD BOWER