Pennsylvania is full of empty buildings — many of them hulking industrial antiques, vacated as manufacturing moved elsewhere. But all is not lost. Resurrection is possible — like at a former Mack Trucks facility in Allentown, now home to the Bridgeworks Enterprise Center.

Bridgeworks, a business incubator run by the Allentown Economic Development Corporation (AEDC), offers space and support for nascent entrepreneurial ventures. Since 1989, it has been cultivating Lehigh Valley manufacturing companies, helping them grow from simple ideas to local job creators.

“Business incubators have become very popular lately,” says AEDC's Anthony Durante. “However, the first business incubator was opened in 1959 in Batavia, NY. In the Lehigh Valley, we were one of two incubators opened in the 1980s, the other being Ben Franklin Technology Partners of Northeastern Pennsylvania's first incubator that ultimately became Ben Franklin TechVentures. I think we took advantage of some available property and a great concept to create opportunities during a time when the Lehigh Valley was struggling.”

The building is currently divided into 16 to 20 suites; the smallest are around 600 square feet. There are common areas, a kitchenette and a co-working space open to all clients.

AECD's goal is for companies to stay at Bridgeworks for four to seven years. The first lease entrepreneurs sign usually for three to four years.

“It's probably a longer period than most incubators,” says Durante. “But for a manufacturing company, it takes a lot of money and energy to get it started; it also takes a lot of money and energy to move a company once it's up and running. We don't want to rush them out of here just as they're starting to get profitable.”

“We're always looking for new companies,” he continues. “Some of it is word of mouth; some of it is me. I spend a lot of time at business events and networking events where I meet entrepreneurs. Some of it is relationships with Ben Franklin Technology Partners. There's no real application. Once we have an introductory meeting with an entrepreneur, we ask them to submit a business plan. We're looking to understand the team that's running the company — you can have an A team with a B product and have a really good company, but if you have an A product with a B team, you sometimes run into issues.”

In the beginning

Wayne Barz, who now works at TechVentures, graduated from Lehigh University in 1987. His first job was with AEDC.

“I was this young kid out of college and one of my first things I was being asked to do was look through a pile of information on my desk about incubators and site plans for this property,” recalls Barz. “Business incubation was a fairly new concept at that point.”

The building's history helped inspire the concept. Mack built truck chassis in about 60,000 square feet of long, narrow space — truck parts came in one end and came out assembled at the other end. The structure had all the assets budding manufacturing companies needed.

“I'd say [incubation] is one of three economic development tools that a community has,” says Barz. “Lots of communities invest a lot of money in trying to attract businesses to their regions. A lot of communities spend a lot of effort and capital on reaching out to the local business community, trying to make sure people are happy and can hold onto those companies. But creation is the third part of that, and I would argue, it doesn't get as much attention — because it's small. The startups we're talking about are one or two people with an idea. It doesn't make a great headline. Entrepreneurs, founders, are the very beginnings of the universe. Nothing exists until an entrepreneur has an idea and starts to pull the resources together to execute it.”

An industrial legacy

The Lehigh Valley is an increasingly hospitable place for startups, in no small part thanks to its industrial heritage. There is a lot engineering talent in the area; many workers are educated at the area's universities and tech schools or trained at local corporations. The key is supporting manufacturing businesses that have a chance to thrive in the changing economy.

“We're not seeing the commodities — the guys who are making 10,000 iPhones,” explains Durante. “I think that will stay overseas, wherever the labor is cheapest. But small-scale or single-product and custom-order manufacturing — or very small scale craft industries, like the craft beverage industry — lower volume, high margin, those are the companies we're seeing being successful. To put very small volume in a container, and ship them from China or India, is very expensive. By keeping it in the U.S., you shorten the supply chain and have much more direct control over the quality.”

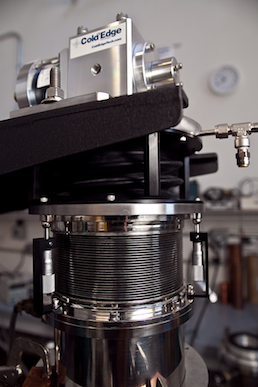

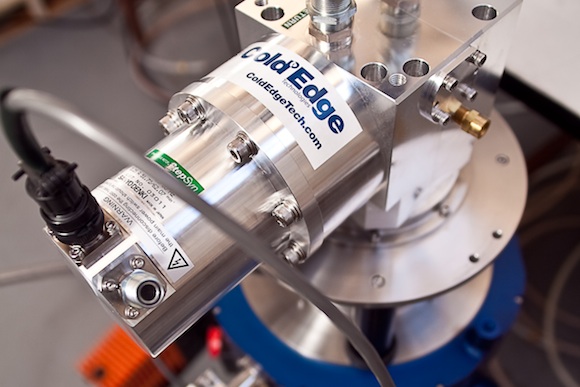

Bridgeworks has an expansive definition of “manufacturing” — if it's something that's made, be it beer, lacrosse pockets or plastics, it can have a home in Allentown. They are even open to tech companies — places that “make” software or apps. Current tenants include ColdEdge Technologies,The Colony Meadery and MTS Ventures; HiJinx Brewing Company and Gonzo Pockets are in the process of moving in.

“What we are looking for — and hopefully what every incubation program is looking for — are high potential companies,” says Durante. “Those that can create 10 to 25 jobs or more while they are in the program. Ideally, that turns into 40 or more jobs as the company departs the incubator and continues to grow. We also look for companies that can get to $1 to $2 million in profitable revenue while in the program. When we come across an entrepreneur with a business idea that looks to have that potential for growth, we get excited.”

The rough economy has required flexibility from incubators and development corporations like AEDC. Since 2012, Bridgeworks has implemented new best practices, adding training seminars for clients, improving the energy efficiency of the building by replacing much of the roof, and expanding the advisory committee and network of resources for their startups.

Success breeds success — one of the incubator's most notable graduates is Luminaire Testing Laboratories, now a division of Underwriters' Laboratories. They were the very first client back in 1989. One of the first employees, Mike Grather, bought the company from the founder in 1991. In the mid-90s, LTL exited the program and became the incubator's first anchor tenant. In 2011, the company was acquired by Underwriters' Laboratories and subsequently moved to a facility in Kuhnville. When the company left Bridgeworks, it employed 45 people. Grather is now on the advisory board for Bridgeworks.

The companies

Greg Heller-LaBelle, co-founder of The Colony Meadery, actually went to business school with Anthony Durante. So, when he and his partner started the company, it wasn't long before they looked to Bridgeworks.

“I was a craft beer blogger and writer for about five years,” says Heller-LaBelle. “I had toyed with the idea of opening a brewery before. When I moved back to the Lehigh Valley, I met my business partner, [Michael Manning], at a beer tasting. He was a very accomplished home brewer, and an even more accomplished home mead maker. He has won a national award or two. When I tasted some of his home brew, I said, 'Have you even thought of doing this professionally?' We're looking at a craft beer segment not only with booming growth, but with a desire for new things. We're seeing ciders blow up. We're seeing an interest in gluten-free options. I don't see any reason why mead [an alcoholic beverage made from fermented honey] can't be the next thing.”

As Keystone Edge explored earlier this year, starting an alcohol-based business is complicated. You have to jump through a lot of regulatory hoops before you even reach production. Manning and Heller-LaBelle started the business in August, 2012; the fermenters were installed in October of last year.

“For us, it took us about 16 months for just paperwork to clear, before we could even get the equipment and start making the stuff,” explains Heller-LaBelle. “For us, having an incubator was really, really important. We had a space that looked good for our needs; it was small — we weren't paying for things we didn't need. And they could work with us.”

“From the moment we moved in, we pretty much instantly made connections,” he continues. “Hiring the plastics manufacturer next door and the industrial designer across the hall who is now a friend of mine. It is nice to have a community even in the building.”

Colony will soon be joined by another boozy business — HiJinx Brewery is moving in across the hall.

“I think it's gonna be a destination,” says Heller-LaBelle. “People right in Allentown will have a place where they can go to try craft beverages that are made locally. In my dream, a distiller could move in, a coffee roaster, a craft soda maker. There's real potential to have a thriving community. There aren't that many of us — maybe five or ten percent of the population — that really has the mindset to start a business and do this insanity. And it is sort of nice, at a psychological level, to have people to talk to who understand the challenges and the life.”

Matt Sommerfield of MTS Ventures shares that sentiment. His company, which was launched in 2005 as a part-time business (Sommerfield went full-time in 2008) does product design and development, helping clients take their ideas from concept to production. They needed design studio space that was flexible for prototyping and manufacturing, and somewhere that had a lot of natural light.

“There's a couple other [compatible] businesses in the building,” says Sommerfield. “There's a plastics manufacturer down the hall; he's machining plastics for his clients. Let's say I need a special tool, I can walk down the hall and say, 'Hey, do you have this?' It's a lot more efficient to share not only the tools but the knowledge on how to use them.”

Sommerfield has also taken advantage of seminars offered at Bridgeworks on legal issues, financing and accounting. Entrepreneurship can be lonely, and the incubator helps combats that isolation.

“With the other business owners in the building, you don't have to explain what you're going through,” explains Sommerfield. “They already know — dealing with cash flow and customers. It's really a unique community.”

LEE STABERT is managing editor of Keystone Edge and Flying Kite.