In June, Keystone Edge hit the road, traveling to the Lehigh Valley for a day at Ben Franklin TechVentures on the Lehigh University campus. We sat down with representatives from five different regional companies, all clients and alumni of the Ben Franklin Technology Partners of Northeastern Pennsylvania, chatting about their goals, their challenges and their affection for the local startup ecosystem.

First in the room was Dr. R. Sam Niedbala from TB Biosciences, a perfect example of technology transfer from the academic lab to the market. The company was initially funded through grants, and then about a year ago, they secured their first line of venture capital funding. They are developing a new method for detecting active tuberculosis.

One third of the world's population already has TB, but it's in a dormant state. About ten percent will eventually transition to an active state. That can happen due to illness or becoming HIV positive — anything that limits the immune system's ability to suppress the virus. And once that happens, just coughing can transfer the disease to about 20 other people.

“It's a really significant public health hazard,” explains Niedbala. “Economically, it also places a strain. There are 11,000 cases per year in the U.S., but we test hundreds of thousands, including health care and school workers. And it's endemic to the most important developing economies in the world: India, China, Russia Brazil.”

The company's technology focuses on the bacteria's genes, reverse-engineering the proteins that are present only when the infection is active. Then, by selecting certain signatures of active TB, they are designing a simple pregnancy-style test. (Niedbala worked on a similar HIV test product at OraSure, his former company.)

“If it works, we could use this in other ways for other infections,” he explains.

Niedbala has worked in medical devices for close to 30 years. He's now on the Lehigh faculty, teaching in the chemistry department. He argues that the region is an exceptionally strong environment for medical device companies — you have the technical expertise, the proximity to major markets and a savvy startup community.

“I'm one of those people that can sit in the room with the finance guys, the business guys or the sciences guys and at least have reasonable understanding of what everyone is trying to say,” says Niedbala. “And that helps us a lot in what we're trying to do here.” (For more on TB Biosciences, check out this recent founders profile.)

Next up was Donna DeMarco from Viddler, an international leader in online video. With clients in 190 countries, they are a company in transition, shifting their focus to keep up with the changing face of the internet.

“We recently did what we call a pivot, in the last six months or so,” explains DeMarco. “We're shifting up, targeting the enterprise component and [providing] a more personalized experience with organizations — a complete solution. We're finding that, even now, a lot of companies don't have a video strategy. Somebody has said they have to put video on their website, so they do and it's a 'set it and forget it' type thing.”

Viddler wants to foster video content that's more responsive, more interactive and more functional. They are targeting the digital publishing market, helping print publications create content that is “sticky” and supports their print products. They also see huge potential in training via video, whether that's working with large organizations that do both internal and technical training, or developing public training content.

“People choose us because we have a very good reputation,” says DeMarco. “We really are customer-centric. If you call us anytime, day or night, someone will probably answer the phone. I say that we are time zone agnostic. We have people that live online — we're a techie company.”

Viddler started at Lehigh and earned support from Ben Franklin Technology Partners of Northeastern PA. When the company grew to more than 20 employees in 2011, they moved the majority of their staff to the Partnership for Innovation (“Pi”) space in Southside Bethlehem. The leadership made a deliberate choice to stay in the community, working hard to foster a vibrant office culture. Four employees bike to work; one walks. On Fridays they have cook-outs.

“People are surprised that we have a tech company in Bethlehem,” explains DeMarco. “We have a great staff. We also get a lot of interns. The majority have turned into Viddler employees.”

In the ultimate sign of startup success, the company has already produced two spinoffs founded by ex-Viddler employees — a YouTube analytics startup and a WordPress-style content management company.

Not all of the companies we met with started in the Lehigh Valley — some moved there seeking oppotunities. Mark Dillon started Bio Med Sciences, a company that specializes in dressings for burns and scars, in 1987 in New York State.

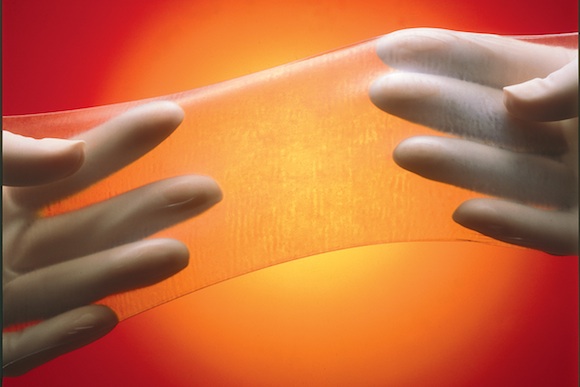

“I developed the basic technology as part of my college thesis project [at Alfred University],” recalls Dillon, explaining the story behind Silon, his proprietary material. “This is a blend of teflon and silicon. Both of those materials have been around for a century or more, but are sort of like oil and water — they don't mix. But I didn't know that, so I just went ahead and did it.”

Silon is actually a matrix of teflon imbedded within a matrix of silicone. The teflon creates a reinforcing mechanism, lending strength to the composite and allowing the use of very soft, thin and adhesive silicons. There is no active ingredient — the silon acts as an artificial epidermis with the silicone component serving as a hyper-moisturizer.

Dillon spent a couple of years working out of his apartment, managing patent applications and cooking up samples of his product in a frying pan. In 1991, he moved to the Lehigh Valley. The company is now based in Fogelsville, west of Allentown. They've expanded their line of products to include other burn dressing products and a line for treating scars (marketed under the name “ScarAway“). They also sell to the plastic surgery market, manufacturing dressings designed for specific types of scars, such as the anchor-shaped ones left after a breast reduction.

From that apartment startup, Bio Med Sciencs has grown to employ 20. They sell into more than 50 foreign countries, and hold a portfolio of about 50 patents.

“I hired my first employee, and he's still with me 24 years later,” laughs Dillon. “I was his pizza delivery kid — that's how I got to know the guy. He's just a gifted mechanic. He doesn't have a degree or anything, but he can build or fix anything.”

It's been quite the journey for an idea that was initially met with a healthy dose of skepticism by the professor overseeing Dillon's quixotic thesis project.

“The dean of the university called me into the office,” recalls Dillon. “He said, 'You invented this on campus with university equipment. The invention belongs to the university.' And my professor stood up for me, saying, 'This was Mark's idea. He didn't pick it off a list. He made it happen. And I think he deserves to own the patent.' So the dean said, 'OK, you can have it — just got become a rich alumni and don't forget about us.'

Later in the afternoon, we were joined by Erik Marsh, director of business development and sales at LifeAire. The company (whose founder Kathryn Worrilow was recently featured in a founders profile) builds and installs cutting-edge air purification systems at IVF clinics. They hope to eventually expand into other sensitive environments such as neonatal intensive care and intensive care.

“We deal with the clinicians on the front end in the clinical setting, and then on the back end we work with architects, mechanical engineers, HVAC contractors and general contractors to install our systems,” explains Marsh. “We have 13 installations so far; we have an additional four that are under contract. We've hit our critical mass — our tipping point — where the message is getting out. We're now nationwide.”

In some ways, the story of LifeAire is simple: Worrilow saw a problem — that ambient air was a complicating factor within the IVF lab — and set out to solve it. In the 2000s, as lab director at Lehigh Valley Hospital, she experienced inconsistent clinical pregnancy rates, usually tied to seasonal changes.

“Right now, moving into summer, people are doing road construction, pesticides are being sprayed,” explains Marsh. “As we're sitting here, there is source air being sucked into this building and blown into this room. We could have Joe, the pesticide guy, going around the building spraying pesticides, and you and I are intaking VOCs [volatile organic compounds].”

Fortunately, adults are tougher than embryos. We have lungs and organs that flush out toxins, mold spores and funguses. When Warilowe noticed those seasonal variations in her outcomes, she also noticed that they were resurfacing the helicopter pad at the hospital. She tested the air, and connected her reduced success rates directly to the VOCs being produced by the paving.

After ten years of research, LifeAire now produces a purification unit that drastically reduces the VOCs in ambient air — the average laboratory generates somewhere in the range of 1500 to 1700 parts per billion; they are at less than 5 parts per billion.

“That's two drops of water in a kiddie pool versus one drop of water in an olympic-sized swimming pool,” says Marsh. “So that's significant.”

In the longterm, Marsh believes LifeAire's systems could eventually reduce overall costs for hospitals by minimizing hospital associated infections (HAIs). These are incredibly costly infections and often strike the most vulnerable.

“Once it's a confirmed HAI, insurers, Medicare and Medicaid no longer pay for the services from that point forward,” he explains. “The hospital might incur, on average, and extra $75,000 to treat that patient — and that comes out of their pocket.”

Allentown's Applied Separations, our final meeting of the day, specializes in using supercritical fluids in the extraction process, whether that's pulling caffeine out of coffee or the oil out of cinnamon. Their process — and the machines they build to facilitate that process — is greener, more efficient and faster.

The company's supercritical fluid of choice is carbon dioxide: it's safe, inexpensive and easy to work with. It can replace traditional solvents such as hexane and ethanol.

“You can take a ground up spice — say cinnamon — put it in a pressurized vessel, introduce CO2, and you can extract the oil,” explains the company's Dan Lewis. “When you're done, you have pure oil, and the CO2 can be recycled or vented off into the atmosphere safely.”

One of their machines is used to measure the fat content of potato chips at Utz Quality Foods. As opposed to sending a sample off the the lab, workers are able to do a quick on-site extraction, separating (and measuring) the fat from the rest of the chip.

Applied Separations has grown to 40 employees in downtown Allentown, and they see a multitude of opportunities coming with this technology.

“The next big thing is textile dying,” says Lewis. “First they used chemicals; now it's water-based dyes. They use a tremendous amount of water for every pound of fabric they have to dye. So, these companies keep moving, running away from environmental regulations. We're working with some companies that are developing dyes that are soluble in supercritical CO2. Then you can recycle the dye. That could bring a lot of industry back to the United States.”

LEE STABERT is managing editor of Flying Kite Media and Keystone Edge.