Even without the stories of what happened in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, there is something haunting about the city's natural features. Steep hills surround the city and driving up them, full forests flash by against the bright blue winter sky. Along the Lincoln Highway, our nations first coast-to-coast passage, land that was once well kept has been abandoned to return to nature. Empty cars shine in football field-sized junkyards and the ratio of objects to people seems skewed.

Visitors to Johnstown don't just come for the food or the charming downtown area — though those are certainly good reasons — they come to feel and to remember.

The city is a monument of sorts, to the decline of domestic manufacturing, the tragedy of the Johnstown Flood and, in a neighboring township, to the 40 brave passengers and crew members of United Flight 93 who sacrificed their lives on 9/11, crashing the plane they were traveling in into an empty field.

The city's unique character comes from its willingness to face this complex history. This is a town that not only embraces the majestic views from the top of its famous inclined plane, but also thoughtfully commemorates the deaths that spurred the city to build it.

The Night of the Johnstown Flood

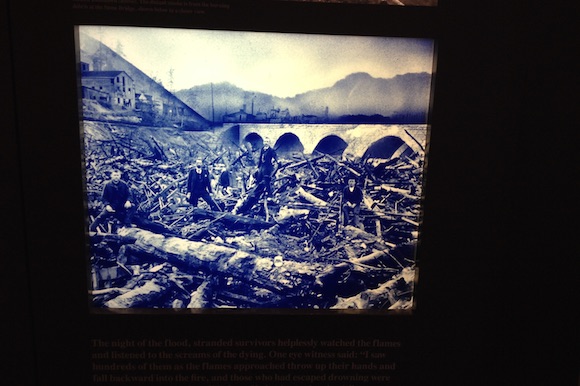

On May 31, 1889, 2,209 people in Johnstown fell victim to an overpowering flood. However, according to a film that plays at the museum, the flood was less a random act of nature than an accident waiting to happen, caused by a few wealthy landowners who wanted to recreate in a man-made lake owned by members of the South Fork Hunting & Fishing Club. The lake was built using a dam, and though the dam was known to be in disrepair, no one did anything substantial to fix it. One stormy night, the dam broke, forever altering local and national history.

At the Johnstown Flood Museum, a timeline of the disaster plays out in graphic detail, complete with a light-up topographical map tracing the water's path from the broken dam to the city's most populated area. A soundtrack of screams rings out like clockwork every few minutes as the map flashes red, showing water crashing into downtown. In one area of the museum, wood and random items are piled up to imitate the ensuing chaos.

Also on display at the museum are stereoscopic photographs taken after the flood. In one of the images, a woman stands above the wreckage with her two children, staring at the photographer with a shell-shocked vacancy in her eyes.

The museum is located in a former library built by steel magnate Andrew Carnegie, who was a member of the South Fork Fishing & Hunting Club and happy there was something he could do to help the city. It holds catalogs listing the names of the dead and personal accounts of survivors such as Anna Fenn Maxwell.

Maxwell recalls losing her husband and seven children, and floating near their dead bodies until help arrived:

“The water rose and floated us until our heads nearly touched the ceiling…It was dark and the house was tossing every way. The air was stifling, and I could not tell just the moment the rest of the children had to give up and drown…what I suffered, with the bodies of my seven children floating around me in the gloom can never be told.”

The famous flood has inspired countless works of art including films, drawings and poems written by Walt Whitman. On the building's top floor, with its almost cathedral-like ceilings and creaky polished wood floors, the artistic and cinematic creations borne from the flood can be found. A large almost Bosch-esque mural featuring the atrocities people endured during the flood is likely less fantastic than realistic.

Heart of Steel

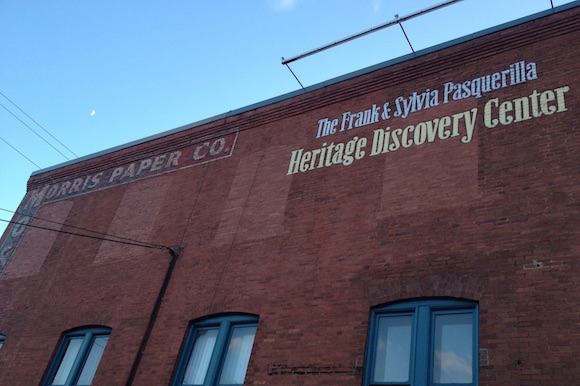

The flood was not the only moment of dramatic upheaval in town — the Frank & Sylvia Pasquerilla Heritage Discovery Center showcases the birth and death of the area's iron and steel industry.

The Cambria Iron Company, founded in 1852, was an enormous engine of industrialization. It was built in Johnstown because the area was rich in coal and iron ore deposits and complete with a readily available water supply. The plant went from making iron to making steel, but after 1973, business waned; the plant closed in 1992.

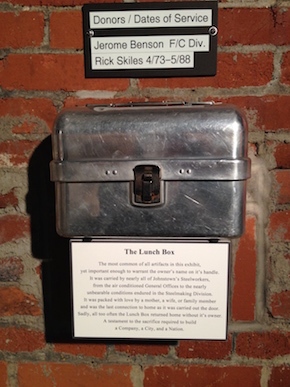

A documentary about the history of the Iron Company plays in a building showcasing the final metal pieces made by area factories and other objects they produced. In the film, the final days of factory work in Johnstown are depicted and the history of steel patents is explored in fascinating detail — but I won't give the whole Bessemer process away.

The Heritage Center also has a wonderful permanent exhibit exploring the history of immigration to the area.

Each visitor is given the ID card of a different immigrant and at various stations, the card can be inserted into a variety of exhibits. I was a young Italian girl, and when I presented my card to a video projection of an upper class woman, she told me which part of the city I would live in and suggested I find work as a maid. Instead, I left the museum and decided to ride the incline after stopping for a hot dog at a colorful and cheap place aptly named Coney Island Lunch.

The hot dog was OK, but a local later informed me that I should have had the cheeseburger. Next time.

Going Up

Night had fallen by the time I drove up to the incline. As I looked out over the city of Johnstown, I was reminded of the topographical map in the flood museum. The view was truly spectacular.

Coming from Pittsburgh, I've ridden on inclines before, and growing up on a small island in New York City, I often rode an aerial tram to school. That said, I was impressed by the Johnstown Inclined Plane, apparently the steepest in the world. Its 30-foot cars travel at the steepest grade for cars of their size. The incline is also open air — there are no seats, no seatbelts, just you inside a slow room-sized rollercoaster car traveling down steep Yoder Hill. I walked into the car without even knowing it, asking the conductor when the next trip was leaving and where I could board.

“You're on board already,” he said to my surprised (and mildly fearful) gasps.

How could an entire room make it down a mountain? I soon found out. The trip down was pleasant if a bit cold and the conductor told me the incline was initially built as a quick way to get residents out of low-lying areas in case of another flood. It can even transport vehicles, though its usually tourists that decide to take their cars uphill in style, he said.

There is a gift shop attached to the incline, and for visitors wishing to enjoy the view for just a little bit longer, Asiago's Tuscan Italian Restaurant is the perfect spot to dine. The restaurant features standard Italian fare with a twist, and for the view, the prices are far more competitive than dining spots in Pittsburgh's upper altitudes.

I ordered the mushroom ravioli with steak tips, which came with bread and herbed dipping oil. I also had a persimmon salad, the day's special, and managed to force a bit of crème brule into my extremely full stomach.

While the food was good, the location, overlooking the entire city and next to the incline, is the real star. As an added bonus, on the way into Asiago's, visitors can have a look at the enormous gears that power the incline.

Make a Weekend of It

Looking to spend more than one day in the Johnstown area? If you're a fan of the outdoors, the Dillweed Bed and Breakfast is a perfect place to stay. Owned and operated by a family, the property features five unique rooms and a formal dining room where breakfast is served daily to guests.

The Dillweed is located in nearby Dillstown, PA, right next to the 36-mile Ghost Town Trail, a multi-use recreational area used for biking, cross-country skiing and horseback riding. The trail gets its name from the numerous shuttered mining towns that used to abut it.

Wehrum, the largest of the former towns, once had 230 houses, a hotel, company store, jail and bank, and was developed by Warren Delano, uncle of President Franklin Roosevelt. There are few remnants of the former towns, but who knows what you may discover. If you don't find any souvenirs along the trail, the Dillweed has a shop selling handmade soaps and candles as well as many other odds and ends, bound to satisfy your roving eye. I bought some pickling spices because when in Dillstown, how could I go wrong.

Recent History

The last must-visit place in the area is the Flight 93 National Memorial in Stonycreek Township, PA.

The memorial is located in a picturesque hilly area. At the site, white marble slabs are engraved with the names of those who lost their lives when hijackers took over a plane traveling from Newark, N.J., to San Francisco, Calif., with plans to crash it in Washington D.C. on September 11, 2001.

After learning that planes had barreled into the World Trade Center in New York City and the Pentagon — and realizing their plane was to be part of an orchestrated terrorist attack — the brave passengers and crew of United Flight 93 overtook the hijackers using what was available to them. Not wanting to risk loosing control of the plane, the hijackers crashed into the field killing everyone on board.

The day the plane hit the ground, locals in the surrounding area felt the ground shake. People made their way out to the field and discovered the wreckage. Victims' family members set up a temporary memorial, eventually raising enough money — while also convincing the National Park Service to buy up land surrounding the site — to create the permanent memorial. As a result, families from New York and San Francisco and those who would otherwise have nothing to do with a rural hillside in Pennsylvania find themselves returning year after year, in a pilgrimage of sorts.

Area residents volunteer at the memorial and some have become intimately connected to site. To create the 2,200 acre memorial, some locals were required to sell their property to the government. They were allowed to remain on the land as long as they abided by certain restrictions on building heights and new construction. Most sellers were cooperative, but some were not and at least one lawsuit ensued regarding the pricing of the land, which was set by the government and deemed too low by one landowner.

The memorial itself is modern and striking — the walk leading up to the white marble slabs is lined with sharp sheer black boulders. Before arriving at the memorial, visitors can read a series of placards explaining the events of the day and look at photographs of the people who lost their lives. Gates bar off the exact area where the plane crashed, but family members of victims are able to visit by appointment.

Each year, visitors from all over the country come to the site, leaving notes on a bulletin board maintained by the National Parks Service expressing gratitude for those aboard Flight 93. On any given day, “God Bless America” or the scrawl of a child too young to recall 9/11 can be found on the board. For those of us who lived through the events of that terrible day, the memorial offers a chance to reflect on perhaps the most significant national historical event in our lifetime. To contemplate the heroism of the passengers aboard Flight 93, all the while wondering, would I have the courage to do what they did?

The memorial is another example of the questions, both historical and personal, inspired by the Johnstown area — questions about the nature of catastrophe and what it means to be a survivor. How does one city absorb so much loss and come out resilient? What is so powerful about an empty field? Can landscape transmit emotion? They are big questions, not the usual fodder for pleasant family vacations or easy dinner conversation, but questions worth asking nonetheless.

ELIZABETH DALEY is a New York City native and freelance writer who relocated to Pittsburgh in search of a better life. Her work has appeared in USA Today, The Christian Science Monitor, Reuters and numerous San Francisco Bay Area publications. Follow her on twitter @fakepretty.