Nestled in Pittsburgh’s charming and historic Mexican War Streets sits the Mattress Factory. This groundbreaking institution, housed in — you guessed it — a former mattress factory, was created by artists, for artists. In that spirit, the institution continues to evolve when the situation calls for it. Two of those transformations happened in recent years. First, the museum agreed to house and digitize the archive of the pop artist Greer Lankton, whose final piece was installed there just a month before her death in 1996. Second, the institution weathered the pandemic, improving its virtual offerings and promoting its collections beyond its walls.

To talk about the power of ephemeral art and the Lankton Archive — why it’s so important and how they promoted it with help from a PA SHARP grant — we spoke with Mattress Factory Senior Archivist Sarah Hallett.

Keystone Edge: Tell us about the Mattress Factory.

Sarah Hallett: The Mattress Factory was purchased by our founder Barbara Luderowski back in 1975. It was incorporated as a museum in 1977 and run as sort of an artists’ collective — they had lots of theater and children’s workshops and artists coming through. Barbara Luderowski was an artist herself.

Over the past 47 odd years — our 50th anniversary is coming up — the Mattress Factory has developed into a site-specific artists’ residency for installation art. What that means is that artists come here, they work in residence anywhere from three to six months, develop a concept for their work, and install their work right here. It’s up for a few months, up to a year, and then it’s deinstalled. We do have a few permanent pieces in our collection: a Yayoi Kusama, a James Turrell, a Sarah Oppenheimer.

We are basically for artists. We say yes to artists. That’s our mission.

I think a lot of people don’t realize that Pittsburgh has a vibrant modern and contemporary art thing going on.

Pittsburgh is a great place for arts and culture. You can go to the Carnegie Museum of Art. There’s the Andy Warhol Museum, which is pretty cool because he was from here. They’re right down the street from us. We’re happy to call it home.

So tell me about the PA SHARP grant from PA Humanities and the project that it funded.

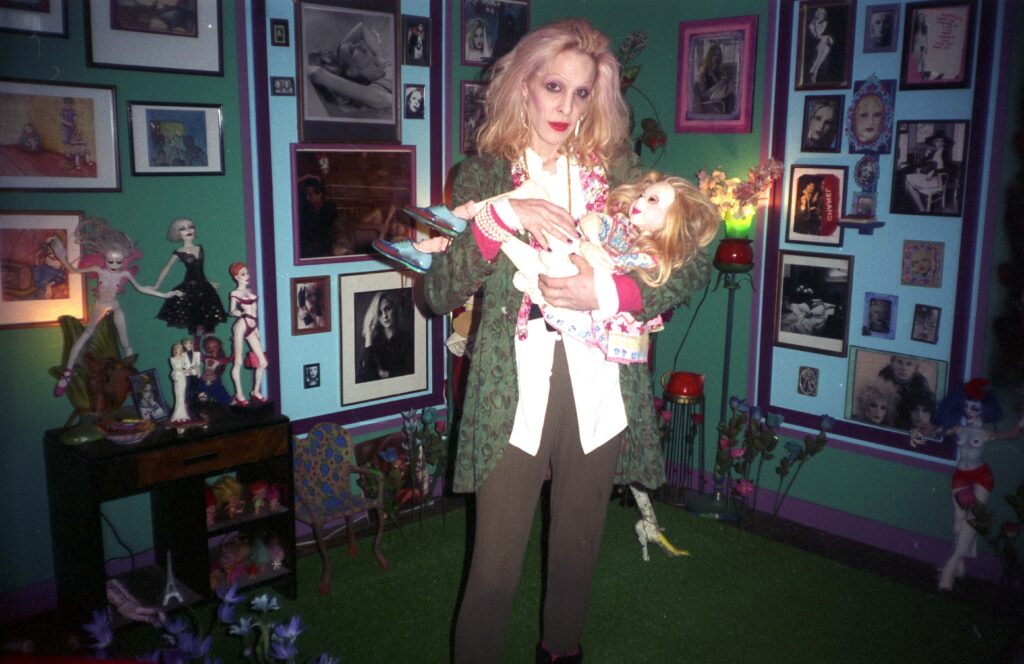

Back in 2019, we applied for a CLIR Digitizing Hidden Collections grant to fund the digitization of our Greer Lankton archive. Greer Lankton was a transgender artist. Her very last installation was installed here at the museum in 1996. It was up for about a year. Her parents donated the installation as well as Grier’s personal archive to the museum in 2009 and 2014, respectively. We started processing this collection and wanted to have it online and available for people to be able to recontextualize her work — to better understand who she was not only as an artist but as a person living in the East Village [New York City] in the 1970s and 1980s.

A lot of art museums that you go to are just this white box. What’s really unique about the Mattress Factory is that an artist can come in here and they can cut holes in the floor.Sarah Hallett

As we were going through this CLIR grant, we applied for a PA SHARP grant to help us run a few symposiums and launch the archive. We had a symposium with local artists, as well as researchers and scholars from different backgrounds. We did tours of the installation itself. Then we had a big birthday bash for Greer. We partnered with a bunch of local LGBTQIA organizations. It was a really nice way to end this long, laborious project.

It’s interesting to think back to 2021 when you were applying for and receiving this CLIR grant. It already feels like we’re in a different moment in terms of trans rights. I think there’s more immediacy because there’s more backlash. This work is coming at the right time.

I would definitely agree with that. We had this collection donated in 2014. We applied for a few grants to get it out there and nobody was biting. I think there was a lot of stigma around this kind of transgender artist and the role that she played in popular culture and art movements. And then all this stuff has happened within the last two or three years, so it’s really a pivotal moment. Being able to publish and present her collection online when we did has brought in so many people. We’ve had people from London come and visit the archive. It’s really opened up this nice big can of worms and put her on the page as a great resource for the LGBTQIA community.

How does the archive contextualize her alongside her contemporaries?

When we’re cataloging something online — posting a picture of an artwork or sharing a journal — our main goal is to be as objective as possible. We describe what’s there, but you don’t really want to imply any of your own personal bias or feelings. You don’t want to imbue any of that onto the archive.

There are so many different categories: there’s correspondence, there’s ephemera, there’s artwork, there’s photographs, there’s journals, all these ways that you can sort of dip into Greer’s life and look at her through a very different lens than just coming to the museum and seeing her installation. I think they complement each other.

With the installation, you get this tragic, sad kind of feeling, and there’s a specific narrative that goes along with that. She passed away a month after she installed the work. But when you marry the installation with the archive, you really get to see that she was this amazing person who had this really deep art practice and was obsessively making work her entire life. She grew up in a Midwestern family. She had good relationships with her parents. She had a lot of contemporaries. I think that looking through the archive allows you to reexamine her as a person and as an artist. People think of her as a muse and you can put her into this trans-feminism, post-pop type of narrative, which is really exciting.

Can you talk about your institution’s experiences during the pandemic?

We had to switch gears really quickly because we started with this grant right when COVID began. So the digitization archivist and I had to pivot. COVID really decimated museums’ income. The PA SHARP grant and the opportunities that it presented taught us new ways of doing things. We had this virtual symposium. A lot of people were able to come. We created a lot of online documentation. Anybody anywhere in the world can go online and see it.

COVID made us question the way that we do things. I think that if we hadn’t promoted the archive the way that we did during the pandemic, there would have been a lot of people who would have missed out on it.

A lot of people have never been to an institution like this — they might think of art as something hanging on the wall and not necessarily something that is experiential and ephemeral.

A lot of art museums that you go to are just this white box. What’s really unique about the Mattress Factory is that an artist can come in here and they can cut holes in the floor. They can completely change the structure and the outlay of the gallery. They can go down one path and then two weeks before opening decide that that’s not what they want to do. We’ll say “yes” to them changing their mind, letting them really sink their teeth into the creative process. It’s great to be able to walk into a museum and see one thing, then you go in a few months later, and it’s completely different.

I’d guess that queer artists and outsider artists have traditionally done a lot more things in an outside-the-box way, going into a space, having it be temporary, having it be on the fly, having it be underground. The Mattress Factory is obviously an institution in Pittsburgh at this point, but you can preserve some of that anarchic spirit. It’s very cool.

Definitely. When you think about the history of the Mattress Factory and where we started — art for artists by artists — it’s almost like a laboratory. You can experiment and do things that you would not be able to do anywhere else.

This story is part of the “We Are Here” series, which has been created in partnership with PA Humanities, an organization dedicated to building community and sparking change.

Funding for “We Are Here” comes from PA Humanities and its federal partner, the National Endowment for the Humanities, as part of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.

LEAD IMAGE: Greer Lankton and her dolls / photo: The Mattress Factory

LEE STABERT is editor in chief of Keystone Edge.