For more than a decade, Dave Goldman co-owned Philadelphia-area restaurant chain Landmark Americana. He was also a seasoned home brewer. His ultimate goal was to combine those passions by opening a brewpub featuring his long-workshopped recipes.

So when Goldman heard about the 18-credit Brewing Science Certificate launched by University of the Sciences in 2015, he was excited for the chance to gain hands-on skills so close to home.

“There’s always more to know about brewing beer,” says Goldman, who studied hotel and restaurant management at the University of Delaware. “When this program opened up, it was a no-brainer.”

When inaugurated, the University of the Sciences’ post-baccalaureate certificate was Pennsylvania’s only college-based academic program dedicated to beer-making. That’s about to change: Starting this fall, students at Pennsylvania College of Technology in Williamsport will be able to earn associates degrees in Brewing & Fermentation Science.

Sure, plenty of people go to college to drink beer, but why are a growing number enrolling to learn how to brew it?

It’s certainly a growth industry. According to figures from the Brewers Association, the United States has more craft breweries – 4,269 in 2015 – than at any time in its history. Pennsylvania has 178.

And while the Brewers Association found that American beer consumption actually dropped 0.2 percent from 2014 to 2015, beer drinkers have grown more sophisticated. That explains why the number of microbreweries has grown the fastest.

With the crowded market, the ability to develop a product that goes against the grain — pun intended — can be invaluable.Matthew Farber

“The big shift is that consumers are requesting more variety,” says Michael Reed, Dean of Sciences, Humanities and Visual Communications at Pennsylvania College of Technology. “The breweries are in need of a workforce that can accelerate their growth.”

All told, craft brewers contributed $4.5 billion to Pennsylvania’s economy in 2014, an economic impact second only to California. These up-and-coming companies want employees who understand the intricacies of the industry.

The Science of Brewing

Most current brewery workers lack formal training in the field. But according to Marisa Egan, a chemist with Victory Brewing Company in Downingtown, they need to understand the science and process behind making beer — and to be able to troubleshoot when something goes wrong.

“People think it’s so easy to put these four ingredients together,” she says. “But trial and error doesn’t really work.”

“People think it’s so easy to put these four ingredients together,” she says. “But trial and error doesn’t really work.”

The associate’s degree program at Pennsylvania College of Technology will focus on technical skills. Classes will include algebra, chemistry, biology and brewing operations. Students can expect to spend three times longer in the lab than in class, says Reed, so they’ll get plenty of hands-on experience. (Only students who are at least 21 will be able to taste-test what they make.) Plans call for an initial cohort of 18. The college has received strong interest from prospective students, including restaurant employees and those with backgrounds in science.

John Callahan, brewing manager at Yuengling, was one industry representative who consulted on the program. In 37 years at the generations-old brewery in Pottsville, he has seen exponential growth in the industry and increased demand for more specialized knowledge. For example, Yuengling operates its own microbiology lab to assess the quality of each batch.

“Years ago you just had the brewmaster — who was an educated person — and the workers,” recalls Callahan. “But it’s not just dumping malt into a kettle. It’s just like a recipe in your kitchen: It’s about time and temperature.”

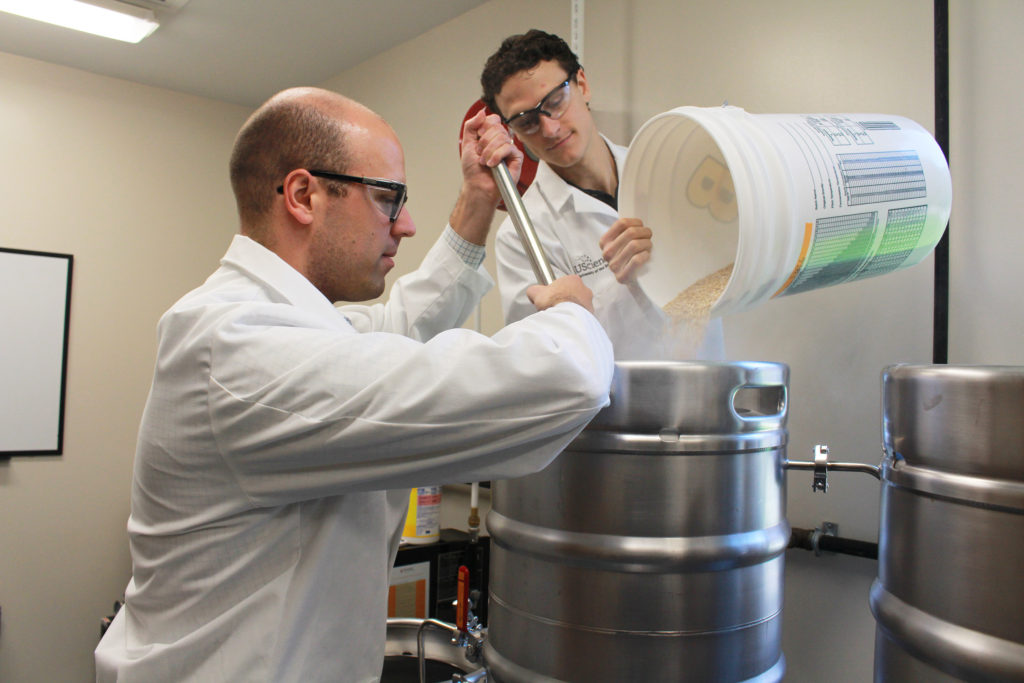

The University of the Sciences’ certificate program, meanwhile, immerses students in research and experimentation. This makes sense when one considers that Matthew Farber, director of the program, is a molecular biologist by training and a home brewer by hobby. As a postdoctoral fellow studying enzymes as part of research on HIV and Alzheimer’s disease, he stumbled upon findings that helped with his avocation.

“It was exciting to apply the research to my home brewing,” he says.

Farber’s connections to chemists and others in the beer industry showed him the market for well-trained employees. The program was designed to target career changers — all classes are at night — and to lure students with backgrounds in biology, chemistry, physics and engineering. The research-based curriculum means participants delve into scientific literature and analyze how flavor changes when different ingredients are used. They also intern at breweries.

Farber’s connections to chemists and others in the beer industry showed him the market for well-trained employees. The program was designed to target career changers — all classes are at night — and to lure students with backgrounds in biology, chemistry, physics and engineering. The research-based curriculum means participants delve into scientific literature and analyze how flavor changes when different ingredients are used. They also intern at breweries.

“With remarkable growth comes a need to remain competitive,” explains Farber. “With the crowded market, the ability to develop a product that goes against the grain — pun intended — can be invaluable.”

Victory’s Egan teaches one of the last classes in the program: Her students develop a hypothesis about how changing one piece of the brewing process will affect the final product. Then they test their hypotheses in the lab, which features a pipe for distilled water that can be customized to mimic the water from any natural source.

Beer is so interesting on every level — not just the science of it, but the flavor of it.Marisa Egan, Victory Brewing

One group from her class brewed two identical batches, chilling one at room temperature and cooling another as it left the fermenter. This single difference in the process resulted in beers with different flavor profiles, colors and protein contents.

“The number of variables that come from each product is amazing,” says Egan. “Beer is so interesting on every level — not just the science of it, but the flavor of it.”

The first six students graduated from the University of the Sciences program in January. Four of them were offered jobs at their internship sites.

Goldman, on the other hand, is launching the restaurant of his dreams. Urban Village Brewing Company is expected to open this June in Philadelphia’s Northern Liberties neighborhood. The menu of brick-oven pizzas and hand-cut fries will be built around a rotating slate of tap beers.

Goldman, on the other hand, is launching the restaurant of his dreams. Urban Village Brewing Company is expected to open this June in Philadelphia’s Northern Liberties neighborhood. The menu of brick-oven pizzas and hand-cut fries will be built around a rotating slate of tap beers.

“This concept is really everything my friends and I like about going out,” he enthuses.

Crafting Sustainability

Bart Watson, chief economist for the Brewers Association, is often asked if the growth in craft brewing is a bubble. The short answer, he says, is “no,” and he sees a clear niche for academic programs designed to train the industry’s future workers.

“It’s still an evolving field,” Watson insists.

In fact, the Master Brewers Association of the Americas has developed standards for these degrees. Schools that apply for industry recognition are examined for their teaching of technical and operational skills, along with the availability of hands-on experience.

Susan Welch, who is leading the Association’s efforts, expects the growth in formal training programs to result in a more diverse workforce in a field where employees tend to hire people they know personally. This will boost an industry that is already having impact across Pennsylvania.

“You don’t need to be Anheuser-Busch to be successful,” she says. “You can be successful in your own community and hire 10 people.”

Rebecca VanderMeulen is a full-time adult education counselor and part-time writer who lives in Exton, PA. She likes fruit and wheat beers.